Pinker, S. (2010). “Mind Over Mass Media.” The New Your Times Online. Retrieved on 23 June 2010: http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/11/opinion/11Pinker.html Summary: Pinker’s article tries to prove the positive affect of new media technologies on mental development. Pinker observes, that the development of information technologies have always caused panic, but such scares usually are for no reasons. As an example, the author connects decreasing crime rate with emerging new technologies. In his understanding “[i]f electronic media were hazardous to intelligence, the quality of science would be plummeting” by scientist are using information technologies. By accepting, that “experience can change the brain” he argues, that new technology is not “a blob of clay pounded into shape by experience” and there are differences between the sorts of experiences. The article points, that the knowledge of accomplished people is one-sided. In Pinker’s opinion people are elementally changing by the usage of a certain technology. The article points that people need to use new technology with self-control. As the author concludes, that “the Internet and information technologies are helping us manage, search and retrieve our collective intellectual output [… and] technologies are the only things that will keep us smart”. Opinion: On one hand I can fully…

Background Knowledge Errors

Background Knowledge, Background Knowledge Errors, Diagnostic Errors, Perception, Pipsqueak Articles, Users

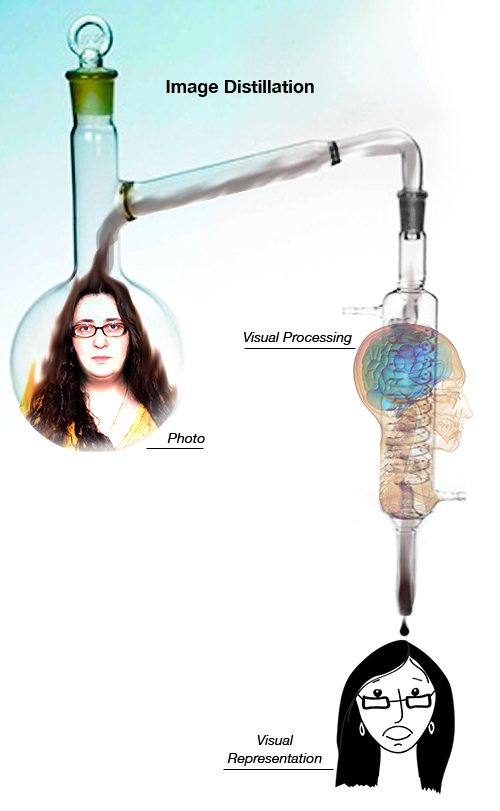

Distilling Information

by Olga Werby •

When it comes to my students’ participation in this blog, it’s all about distilling information found in the news to something product designers in our midst would find useful, on a practical level. Consider the illustration below. We see a person’s face (mine in this case). We can describe some of the features. But what do we actually remember? Remembering complex visual information is hard—too many details. Recalling a drawing is easier. That’s because an artist already distilled the complexity into its essential parts—only those details that are required to remind us of a particular individual are included in the rendering. We are all pretty good at judging wether a portrait looks like the person it was intended to represent. We can quickly say if it does or if it doesn’t. But it would be difficult to explain what details in the illustration make the likeness or what’s missing from the drawing that didn’t hit its mark. Distillation of information is hard. Some people are good at it, some are not. It’s an acquired skill. And each category (e.g. sensory like visual, audio, tactile or knowledge-based like physics, economics, biology) requires its own training and its own set of talents.…

Background Knowledge Errors, Pipsqueak Articles

Complex Nonlinguistic Auditory Processing

by Olga Werby •

aka Music. Today, I read a short interview on New York Times where Aniruddh D. Patel answers a few questions about his research into the neuroscience of music. The interview was pretty entertaining—we’ve all seen the YouTube video of a dancing cockatoo. But what got me was the last line on the difficulties of getting funding for research. In particular, getting money to study music was just not possible. So to keep his scientific research sounding like serious science, Dr. Robert Zatorre, one of the founding fathers of this field, used to write “complex nonlinguistic auditory processing” every place the word “music” should have been. To avoid structural research failure, Dr. Zatorre resorted to linguistic manipulation. And it worked! “Exploring Music’s Hold on the Mind: a Conversation with Aniruddh D. Patel,” written for New York Times by Claudia Dreifus, and published on May 31, 2010.

Anchoring Errors, Background Knowledge, Background Knowledge Errors, Diagnostic Errors, Mental Model Traps, Pipsqueak Articles

Working Memory Limitations vs. the Size of Problem

by Olga Werby •

The illustration above comes from Wikipedia, which has a complete entry on the Asian proverb about blind monks who examine an elephant and generate multiple hypotheses of what it could be. In product design speak, these monks are doing collaborative problem solving with a shared goal of identifying a mysterious object—the elephant. The monks, the story goes, all come from different backgrounds: an old tailor touching an elephant’s ear describes it as cloth; an aging gardner hugging the leg imagines a tree trunk; an elephant’s tusk is envisioned as a weapon by an arms master. Each monk brings his own life’s worth of experience to bear on the problem, but each has very limited access to the whole. It’s easy to see how this story can be used to explain the pains of collaborative and cooperative group projects in which individuals focus on product design. Each person brings their own expertise to the table, hopefully contributing positively to the whole process. But this story is also a good metaphor for understanding problem solving in context of our very limited working memory capacity. Unlike elementary school math problems that we all calculated, real world problems are messy and don’t come with…

Background Knowledge Errors, Causal Net Problems, Conceptual Design, Diagnostic Errors, Featured, Interaction Design, Interface Design, Pipsqueak Articles

The Anatomy of Failure

by Olga Werby •

On May 7th 2010, at around 2:30 p.m. Eastern Time, the stock market went on a wild ride, dropping over 900 points in matter of just minutes. What happened? There’s lot’s of speculation, and some know more then they are willing to say. But what’s clear is that there was just the right confluence of world events, human and computer errors, and system-wide communication breakdown that triggered a mass sell-off of stocks at fantastic prices. In other words, there was a catastrophic failure during product interaction. I’m not an investment analyst and have limited knowledge in this subject area, but I am interested in product failure. So Thursday’s stock market episode was very interesting. Here’s a little background on the events of that day broken down into steps leading to the failure. Step 1: When the New York stock market opened on Thursday, bad news was streaming in from Europe—there were fears that Greece would ultimately default on its loans; its people were staging massive demonstrations in Athens; Euro was going down. Step 2: In our very interconnected world, this kind of news makes investors skittish and the stock market was dropping value all morning. Step 3: At around 2:45…

Attention Controls Errors, Cognitive Blindness, Featured, Misapplication of Problem Solving Strategies, Pipsqueak Articles, Product Design Strategy, Scaffolding

Neuro-Parasites & Problem Solving Errors

by Olga Werby •

Dr. Robert Sapolsky is a professor of neurobiology at Stanford University. He started his career studying baboons, charting the relationship between stress hormones and an individual animal’s social ranking in the baboon society hierarchy. The lower the rank, the more stress the animal experiences, the more consequences there are to the health outcomes and longevity of the baboon. Making a parallel to human society, the conclusions of Dr. Sapolsky’s study is that it sucks to be at the bottom of the social order. In his books “Primate’s Memoir” and “Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers,” Dr. Sapolsky provides copious details of his work and his conclusions. (see Recommended Books for details) But residing on the bottom of the social ladder is not the only problem a mammal like us can experience. In his video interview with Edge (www.Edge.org), Dr. Sapolsky describes the adventures of Toxoplasma–a protozoan parasite carried by cats which causes an infection Toxo–in our amygdala. Post an active infectious state, Toxo is able to manipulate human dopamine levels. People with the post-Toxo infection have higher than normal dopamine levels, resulting in some interesting cognitive consequences. There’s been solid research that documents a high level of Toxo infections in schizophrenic patients. There…

Conceptual Design, Diagnostic Errors, Featured, Pipsqueak Articles, Users

More is Better: Why iPad doesn’t Satisfy Everyone

by Olga Werby •

There have been a lot of complaints flying around about how iPad doesn’t do this, and iPad can’t do that, and iPad won’t work with that other thing. Some people are so obsessed about all the things that iPad isn’t capable of doing that they overlook all that it can do. By looking for failure, these reviewers lost sight of what iPad is all about. There are plenty of people who are defending iPad out there, so I was interested in why the people who dislike iPad so passionately feel the way they do. We, the people, tend to make our decisions based on little snippets of information that we find to be true and productive for solving various problems. “If something is steaming, it must be hot.” “Big things fall harder and faster.” “Where there’s smoke, there’s fire.” “If one is good, two is even better.” “If it looks clean…” “Little kids don’t lie.” “If it’s natural, it’s not chemical.” “Summer is when the Earth is closest to the sun.” “One can’t get fat eating vegetables.” These are the building blocks of our intuitions. We are all walking encyclopedias of folksy wisdom—common sense explanations that are consciously and unconsciously…