People who are happy are able to turn even routine tasks into play. Or perhaps it is the other way around — people who can to turn routine tasks into play are generally happier. We know that people who manage to turn repetitive and tedious tasks — like working on an assembly line in a factory — into a game, manage to thrive as compared to those who see only boredom and frustration. People can engage with any task by gamifying it. Yes, that’s why that word gets thrown around a lot — a design constrain that aims to turn monotony into a fun activity. The problem with gamifying is the nature of a play — what makes a game fun for one person might not work for another. For me, creative writing is a play of the mind, but it is probably a punishment for others. As they say, “it’s nice to have written, but it sucks to write.” But when I write, I’m free. It’s the most exquisite of games for me.

In life, there are tasks we have to do and those we get lucky to do. My grandmother cooked dinner for our family for decades, as ungrateful and blind as we all were to her hard labor of love. Day after day, month after month, year after year…she didn’t get tired or complained. She managed to find joy in keeping us fed. I didn’t find that remarkable until I had to do it. I am a grandmother to a two-year-old girl who lives with us (her father, my son, does too). We don’t get out much anymore. So I do think about planning our meals and getting the ingredients and then putting together meals so that we get a bit of nourishing joy at the end of a hard day. It’s a daily and repetitive task, and I can set my mind so that dinner preparation can become a nightmare, but instead I dance to music I love and have a great time putting it all together (shopping still sucks, though). I found a way of injecting joy into a routine activity. I don’t know how my grandmother did it, but I am sure she gamified meal preparation, too. She made family dinner management and cooking fun for herself. And she was proud of it — that’s part of gamification, too. We feel proud when we win! So part of the strategy is to arrange a win at the end of the activity.

Most of such games of the mind are games that are played with/against oneself — walk a mile farther than the previous day; do more stairs this week than the previous; beat one’s own time on task completion; combine several activities to break up monotony; try new things within a particular activity (e.g. like a new recipe); share achievements publicly or keep a record (e.g. Instagram, TicToc); etc. Most of the times, it’s not about what others can do or whether they can do it better; it’s about personal satisfaction. And games are never passive — we have to be active participants.

Humans are game-playing animals — we need to play in order to keep ourselves sane.

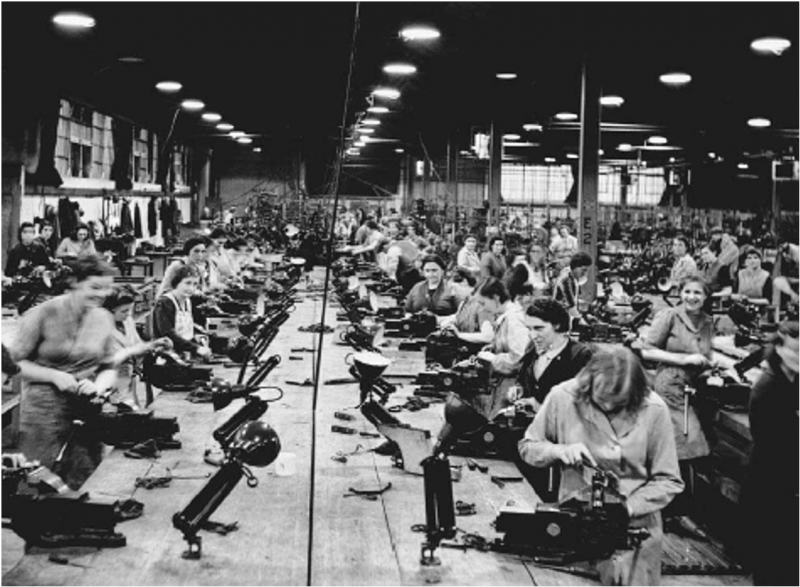

CAPTION: Notice all the smiles and happy faces on the floor of this manufacturing facility — among all the hard work, there was joy! Take that joy away, and the quality of the product will go way down. Because the opposite of play is not work, it’s depression.

As you know, I have had a hard time picking up writing in the last three years — life seems to severely truncate the amount of head room I have for this activity. But writing requires large mind vistas in which to unfold a story. Writing is problem solving, juggling competing storylines and ideas, choosing which characters to keep and which to kill, finding creative workarounds to dead ends, etc. A writer needs a lot of uninterrupted time to write, at least I do. But there might be a flicker of stability entering my life — I might get every other weekend of uninterrupted time. This should help. I have many stories that are in various states of unfinished. One, The Tinkerer’s Daughter, is particularly good and worthy of the time it needs to get finished. It is something like The Count of Monte Cristo mixed with Gallum embedded in a Russian fairytale and set in the years of Russian Tzars at the start of the Industrial Revolution. It is steam punk and magic and tragedy of Russian proportions enriched with psychological twists and with a sprinkling of engineering and metallurgy. I forgot how good it was… Here are the first few paragraphs before Book One of the story (it reads and writes well with Sergei Prokofiev, I find):

My name is Manya Dimitrievna Remeslennikay, daughter of a famous tinkerer, Dima Dimitrivich Remeslennik, and his beautiful, raven-haired wife, Lyla. Yet they call me Baba Yaga, the bone-legged witch. But calling someone by an ugly name doesn’t make that person ugly or the occupation true. I got my bone leg as the result of a childhood accident. Many children get maimed and many die in small settlements in rural Russia. No one here survives to adulthood unscathed. I suppose that’s true all over the world, too. Kids are fragile and resilient. One can be both.

But it takes more than a childhood accident to earn the moniker of a witch. It takes a village…and a city. And a bunch of nasty and stupid people who can’t tell the difference between a strong educated woman and dark magic.

So be it. I have written down my story as I remember it, as I managed to piece together events from talking to other people, including those who were not my friends, and from simply guessing at the truth. I’m a good guesser. If you are reading this, then you have discovered my secret stash of notes, engineering drawings, architectural designs, my personal observations on how this world works. And, most importantly, if you are reading this, I’ve been dead a while. But know that I am no longer bitter…at least not in my death. I did manage to get wiser about the company I keep before then. So all those tall tales of the nasty, bone-legged witch that flew around in a bucket? Well, some of them are true.

I hope you will be interested in picking up the book when I’m done with it.

Happy reading!