How does one choose a story? Or does a story choose its teller? For me, random triggers in my subconscious coalesce and spark inspiration that is not yet a story but rather the embryo of one. That seed, with time, might ripen enough to be worth planting. But the seed of a story doesn’t contain a compelling narrative that grabs and doesn’t let go until the very last word and beyond. A good story stays with its reader long after the last word is seen or heard. It rises unbidden in the middle of the night to infiltrate the reader’s dreams and deliver something new — a melding of what the author was trying to tell and what the reader took away.

What does it take to develop a good story? A spark of imagination is one. Persistence is another — it takes time and perseverance to get words down on a page. But there’s more. I believe that good stories, like all good products, are constructed following a design process. There are always constraints on how the story needs to be told for a specific audience. There are industry demands on authors. There is a ton of background research. And there are just good writing practices that make the story more enjoyable to read — readers notice even if they don’t necessarily know why something is written well. There are rules to writing a good tale, and good writers follow them.

Designing a Product

Long before I ever published my first novel, I spent my professional life designing products: everything from websites to museum exhibits, children’s software to banking applications. I work with my husband as a partner, and we have a standardized approach to the product design process. Briefly, we start by understanding the needs and goals of our clients. Then we try to figure out who the audience is and what they really want from the product. We try to find how the goals of our clients and the goals of our clients’ users can be met with a designed product. There is usually an intersection between those goals, needs, and wants that becomes a set of constraints on the product’s design. Sometimes, the solution is reasonably obvious. But, in the hard cases, we look for the solution by breaking up the task into conceptual design, interaction design, and interface design: What will the product do? How will it do it? And how will it look and feel? On our company website, we’ve written about our design process in more detail.

Decades ago, when we first started in this business, human-computer interaction and interface design were just an afterthought in the world of business. I remember a strange meeting with the CEO of a very successful start-up lecturing us that it was a waste of money to consider the needs of the end user! Fortunately, things have changed. That change improved the lives of countless of people. Don’t believe me? Just consider all the emphasis we now place on usability as compared to back in the day when most of the emphasis was on appearances. It was believed that people bought things based on how good the package looked. If that was true, why waste time, money, and effort on good design?

Every design problem has constraints. Here, I’m not sure the designer successfully navigated them.

There are many different solutions to each user problem. Finding what works best is what good usability specialists and product designers do.

Some design solutions came in layers, one on top of another, as new regulations required accommodations for users with varying abilities. In this case, Braille labels were added to the existing elevator interface. The results cannot be described as user-friendly.

Books and Good Design

Books are also designed products that have evolved over the centuries. Many credit the Victorian Era (1837-1901) with the popularization of the novel as a consumer product. However, “Robinson Crusoe” by Defoe was published over a hundred years earlier, “The Tale of Genji” by Murasaki Shikibu was written in Japan in the 11th century, and thousands of Greek plays and other fiction have survived from well over two thousand years ago. From the handwriting of scribes to the printing press beginning in the 15th century through to modern day, the actual physical book has gone through a myriad of changes and design adaptations.

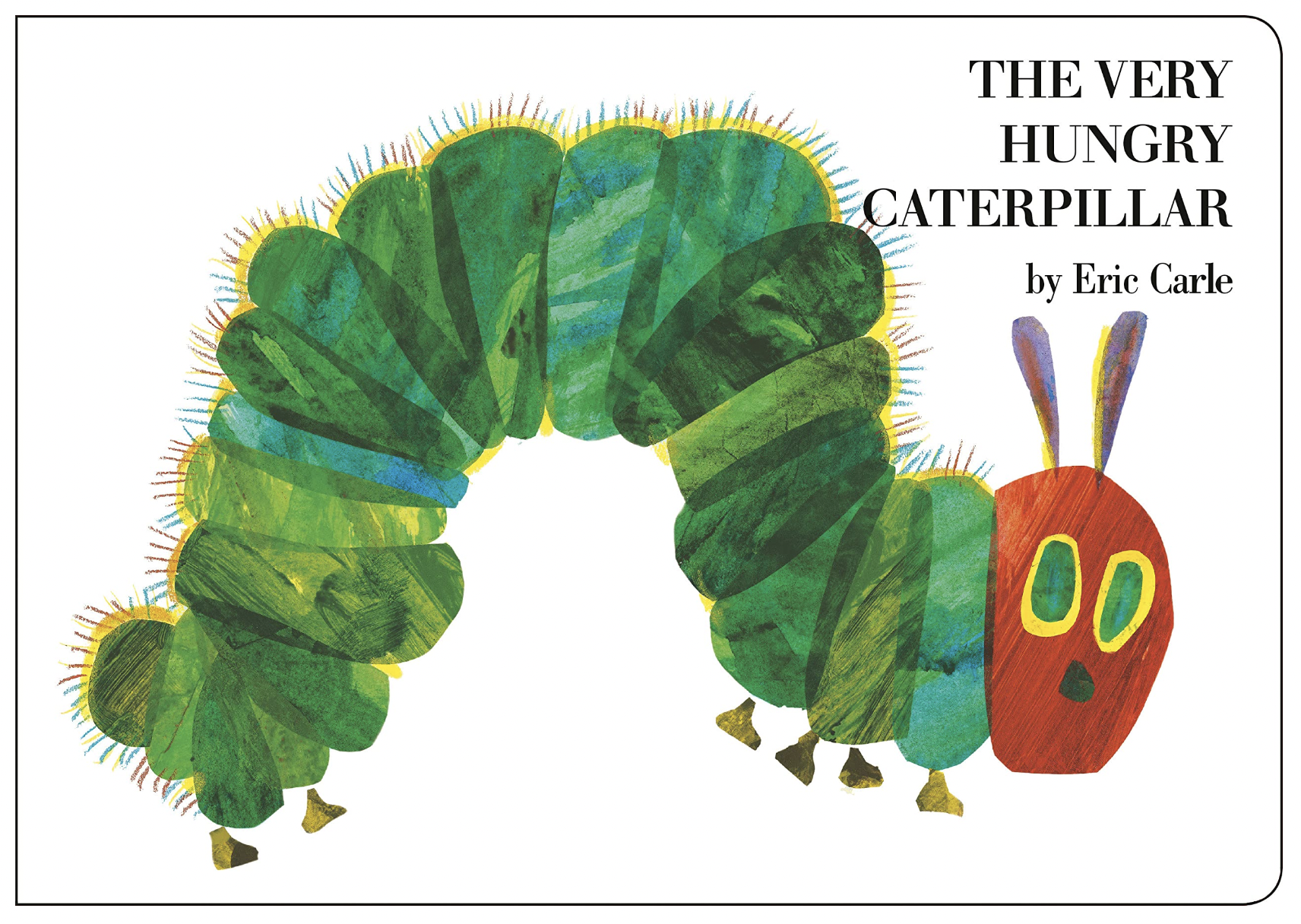

We have a granddaughter now. She’s a little over one year old and she loves books. She enjoys turning the pages and pointing out what’s in the illustrations. She doesn’t talk much yet, at least not clearly, and her dexterity with pages is still limited — paper rips easily when turned with exuberance. So, for now, we prefer books made out of thick cardboard and reduced in size to make the pages easier to handle by little hands. Thick, small pages are easier to turn, they don’t rip, and the book lasts longer. Many classic children’s books — like “Good Night Moon” and “The Very Hungry Caterpillar” — come in the board book format. Their publishers understood the problems facing young children and their parents, and they designed a version that would solve those problems without compromising the content of the book. A product must function well and deliver a good experience for its intended audience. Thinking about the users for a product, even a book, matters.

Above is a cardboard version of the book but there is also a hard cover book with a jacket. We have both editions. I hide the one with the jacket — it already ripped once, and I’m worried about paper cuts on those precious little fingers.

A book is more than just its words. Like other products, it has conceptual, interaction, and interface design elements. Books have pages of a certain size and weight, page numbers, chapters, tables of contents, glossaries, bibliographies, dedications, publishing information, author information and author notes, prefaces that might or might not be written by the authors of the story, maps, graphs, and other illustrations with or without captions, large first caps that signify the start of a new chapter or section, running footers and headers, chapter breaks or section break indicators, headlines and footnotes, and so on. Ebooks have additional features, which I personally use often — dictionaries, text enlargement and font choice, book progress measured in time, reader notes and bookmarks, quotation sharing, access to Wikipedia and other online resources, length of time before the batteries run out, brightness controls, audio adjustments, zoom functions, just to name a few. And ebook screens have to work in all kinds of lighting environments — a challenge that only recently has been overcome. All of these features weren’t born from a story any more than seatbelts arrived with the invention of an automobile. They were invented to improve the readers’ experience. When a book is well-designed, it enhances the experience of reading of a good story; a bad story can’t be saved by good design just as comfortable seats won’t save a car that doesn’t run.

There are other things that have to be considered when a product is meant for a particular audience. A good story that is badly edited leads to a poor reading experience; while a bad story can’t be saved even by great editing. Then, there is age-appropriate vocabulary. Obviously, vocabulary appropriate for adults (and I am not just talking about foul language or explicit content) are not meant for middle grade fiction. When writing for a younger audience, writers have to be cognizant of the language they use. If words get in the way of comprehension, then they are not doing service to the narrative.

However, there are times when unusual words are necessary for the story. In my somewhat strange novel, “Lizard Girl and Ghost”, I intentionally used peculiar word choices to inform the main character. To ensure my readers enjoyed the strangeness and were not frustrated by it, I always included the definition of each of my delicious verbal ticks along with the word itself. Anthony Burgess in “A Clockwork Orange” chose to let his made-up words stand undefined except by context. Word choice and vocabulary is a critical consideration for the target audience, especially if they are young or inexperienced in the book’s subject matter.

Another critical attribute is the story’s length. Each audience, as divided by age, has a preferred length, and each genre has its optimum length. An average adult novel is around 80,000 words, while an epic fantasy can run over 100,000 words. Romance and cozy mysteries tend to have lower word counts, while young adult books are about 75,000 words long. Middle-grade fiction typically hovers around 50,000 words. While the length of books has increased over the last few decades, readers have specific expectations. They know what they like and how long it takes them to consume a story in their preferred genre. If the story is too long, readers can’t finish it in the time they’ve allotted. On the other hand, if a novel is too short, readers may feel cheated. Therefore, writers tend to write within a specific word count range. If the story runs away from the author, there is always the possibility of a second book, provided the first book had a good ending and sold well.

There are many “tricks of the trade” when it comes to good writing. In Elements of Fiction Writing, Orson Scott Card, an author I like and read often, suggested one that I follow in my writing to help readers distinguish between the characters in a story — start each character’s name with a different letter. When reading, many people rely on visual recognition of the word’s shape and do not carefully read each word. If there are too many characters with names starting with the same letter, they start to “bleed” into one another, making the story hard to follow and lowering reading enjoyment.

Representation Matters

We all want to tell the best possible story in the best possible format. Beyond choosing a compelling subject, writers who know their target audience choose their leading characters carefully. When I was young, I stopping reading Jules Verne when I realized that only the boys went on adventures and the girls stayed home and waited for their safe return. After noticing this, I couldn’t enjoy his stories anymore. Readers want to see themselves as action heroes. They want to read about people like themselves — similar gender preferences, tastes, socioeconomic situations, genetic makeup, cultural background, and even physical handicaps. After a car accident in my early twenties, I walk with a cane, even in my dreams (when I’m not flying). While variation is acceptable, I like to read about women roughly my age, similarly challenged, who have had experiences that I can relate to, even if they are aliens from another world.

Representation matters. My main characters tend to span the spectrum of ability, age, sexual orientation, and background. I like characters who face a challenge. I write about homeless kids who save the world, autistic children who overcome all that life throws at them, grandmothers in wheelchairs kicking ass, and so on. Stories should be as inclusive as possible because it makes them relatable and memorable. All writers want their readers to be moved by their work and have the story linger in their minds long after the last word fades from memory.

All writers think about plot and characters. But thinking about a book as a designed product helps a writer visualize their readers and craft an experience to resonate with them.