Chapter 1: Second Visit

March 2, 1953

Olkhon Island, Lake Baikal, Siberia

The man was dragging the boy by his ear, practically lifting him off the ground. The boy made whimpering sounds, but didn’t scream.

“I’ll teach you and your vermin friends,” the man yelled, adding curses and foul expletives in a deliberately theatrical manner. A small crowd of spectators started to gather. Entertainment was hard to come by in the little fishing village on the shore of Lake Baikal, deep in Russian Siberia.

The man dragged the five-year-old boy to the side of the road, where a crop of stinging nettles was still standing from the season before. He grabbed a bunch of stalks with his gloved hand, then tried to rip the pants off the boy, who was squirming to get away. “I said I’ll teach you!” the man yelled again.

He planned to whip this midget criminal. No one stole from Gleb Gregorivich. No one!

Another of the fisherman spoke up. “Hey, the kid wasn’t even the one who took your fish. It was one of ’em older boys.”

“It’s not my fault his legs are short. He should have run faster,” the man snapped back. “He’ll make a fine example for the others.” He finally managed to expose some bare flesh on the boy’s back. “Vorov isn’t doing a good job with the boy. Vorov–even his name means thief. So I’ll teach him myself.”

The old man lashed the clump of dried-up stinging nettles right across the boy’s naked skin. The boy screamed as red bloody lines bloomed on his back–the result of not only the force of the blow, but also the stinging poison in the nettles.

Gleb raised his arm to hit the boy again, but someone grabbed his hand and twisted it behind his back. He yelped in pain, cursed, dropped the boy, and fell to his knees onto the frozen mud of the road. The boy quickly scrambled out of reach.

“What are you—” Gleb stopped short when he saw the man twisting his arm.

The man was tall–much taller than the other men gathered around–and too well dressed for a local. Even here, in the backwaters of Soviet Russia, a man was judged by the clothes on his back. And this man was dressed to impress. He wore a full length, double breasted, forest green wool coat, in the latest European bourgeois cut, with a dark fur collar that accentuated his broad shoulders. His fedora was a matching green with a dark silk ribbon, and his impeccably fitted gloves were a slightly deeper shade of green. In his left hand, he held a cane made of black wood with a golden handle, intricately carved with geometric patterns. His eyes were hidden by small dark oval glasses wrapped in gold rims.

Next to him stood a woman who was equally well dressed, but in black and pink colors rather than green. She wore a similar pair of gold-rimmed glasses.

In Siberia, well dressed usually meant warm. But these two were elegant, which probably meant they were big shots from Moscow, out here on official business. Just one look at their clothing would make people jump, trying to avoid trouble. High-ranking government operatives who found themselves so deeply exiled from Moscow to Irkutskia Oblast must have displeased someone very high up. And that made them doubly dangerous—both powerful and punished. There was no predicting what people like that could do.

The residents of Olkhon Island instinctively shied away from the couple, giving them plenty of room.

After a few heartbeats, the man in the green coat let go of the old sadist, who scurried away in a hurry. The crowd of onlookers quickly dispersed. No one wanted trouble out here. Soon, only the couple and the boy remained.

The fashionably dressed woman looked down at the boy with concern. “Where is your mother?” she asked. She spoke with a proper Russian accent, marking her as a stranger to these parts.

The boy’s eyes got big and his whole body trembled. He seemed so lost, so small. He looked around as if trying to figure out which way to run, where to hide. There was something feral about his movements.

The woman reached out to touch him, but her companion pulled her hand away.

“It’s okay, Erdene,” the man said to the boy. “We’re friends of your mother, Bolorma.”

At the mention of his own name and that of his mother, the boy froze again. He tried to look the man in the face, but couldn’t do it. He was like a small wilding, scared of any attention from strangers.

Finally, the boy seemed to come to some decision, and he ran. Dodging between the dockside clutter, he disappeared behind a low structure across the street from the piers.

“Let him be,” the man said to his companion. His expression radiated a mixture of pain and anger.

“Those welts on his back and shoulders looked bad–” the woman started, but the man cut her off.

“Stop that, Angie,” Paris Urt practically growled. They were now alone on the street.

Angie shivered, pulling her black fur coat tighter around her neck. Her delicate long fingers, covered in shocking pink leather, sank into the thick, silky dark strands of animal fur. “Bolorma will find out about Ira’s release soon enough. It is probably best that we are not around for that. Let’s go.” She snaked her arm around Paris’s and pulled him back toward their boat. Reluctantly, the man allowed himself to be led away.

The Urts’ boat was boxy and top heavy with a shallow flat bottom. In March, the ice of Lake Baikal was still too thick to break–meters thick in some places–so the boat had been lifted onto a large sled. Most of the smaller local boats had been pulled out of the water for the long winter, even though the icebreaker had resumed its semi-regular service between Olkhon Island and the mainland. The locals preferred to drive automobiles right over the lake, or to saddle a dugout over two pairs of skis and equip it with a sail–the fastest way over the ice. But skis and dog sleds were the most common means for getting from place to place in the winter months.

As they climbed aboard, Paris looked over the edge of the boat at his reflection in the thin layer of crystal clear melt water on top of the ice-covered Lake Baikal. He wore the body Bolorma had picked for him, the one they’d helped design and program together. This was the body she said she’d love forever. But would she even notice him now? Would he have to let her go? Would he be able to let her remain in the arms of this Ira, a prisoner in a Siberian gulag?

Ira Vorov was Bolorma’s husband and the father of the scrawny putative fish thief that Paris and Angie had just rescued. Ira was also a Zek–a political prisoner in a gulag–exiled to Siberia from Leningrad by Joseph Stalin during one of his purges. After World War II, there were almost two and a half million Zeks just like Ira, scattered in thousands of gulags all over rural Russia. His crime? “Treason against Soviet Power.”

Ira hadn’t actually committed treason–he hadn’t even planned on doing so. But taking action wasn’t required before being sent away to die in a gulag. Thought crime was enough. And that was easy to prove. Did Ira act scared when the police came for him? Yes? Well, there’s the proof! If he hadn’t done something wrong, he would have had nothing to be afraid of.

It didn’t help that Ira Vorov was Jewish. That in itself was a high crime during Stalin’s reign.

Ira’s sentence had started with back-breaking labor: constructing a railroad through the tundra of Siberia. It was expected that he would die there. But after a few long months, he had met a beautiful woman, and for some reason, she liked him. After that, he was inexplicably transferred to the gulag in Peschanoye Selo, a small fishing village on Olkhon Island, the biggest island on Lake Baikal.

Zeks sent to Olkhon were the lucky ones–they got to work in a fish factory canning omul, the local fish, which beat digging through the frozen dirt. And it was this lucky break that had kept Ira alive for the last seven years, while most gulag prisoners, sent to work in the metal mines or on a railway project, lasted only about eighteen months. Ira knew he was lucky; he just didn’t know to whom he owed his luck.

Paris and Angie were in Siberia to orchestrate luck for Bolorma and her son. They were to make sure that she and Erdene survived the upcoming upheaval. The Urts had done the calculations and knew that Stalin would be dead within days. Bolorma was one of their own, and the Urts took care of their own. Ira Vorov’s survival was also desirable–he was Erdene’s father, after all–but not necessary, in Paris’s opinion. Paris hated the man—or, more accurately, he hated the fact of him–but Bolorma loved him. And that changed everything.

Angie maneuvered Paris belowdecks, down into their cabin, and locked the door. “Come, Paris,” she said, trying to pull him out of his dark thoughts. “I am starting to feel it–I’m feeling sick. I have to go back to our side now,” she added, her hands shaking.

Paris nodded, then began stacking their traveling trunks into a complicated arrangement. The cases of hard luggage strewn about the cabin snapped together like pieces of a three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle.

Angie watched him work and worried about him. He vacillated between being sad, angry, and erratic. She wondered, not for the first time, when he might snap. She felt sorry for the wretchedness of his situation, even as she envied Paris his deep mating bond with Bolorma. She wanted that kind of bond for herself and hoped against hope that someday she would find a soulmate for herself somewhere on Earth.

Paris pushed his cane into a slot generated by the geometry of the stacking pyramid of luggage, and the structure clicked together. Then he pulled open the lid of a wooden trunk that rested on its side at the base of the structure, and from inside, bright white light flooded the dim cabin.

“Come,” he said, extending his hand to Angie.

They climbed inside and closed the lid behind them. The cabin was dark again.

From behind discarded old fishing nets and rotting barrels, Erdene watched as the windows on the boat lit up with a piercing light for just a few heartbeats. And then it was gone. His back itched terribly in the afterglow.

***

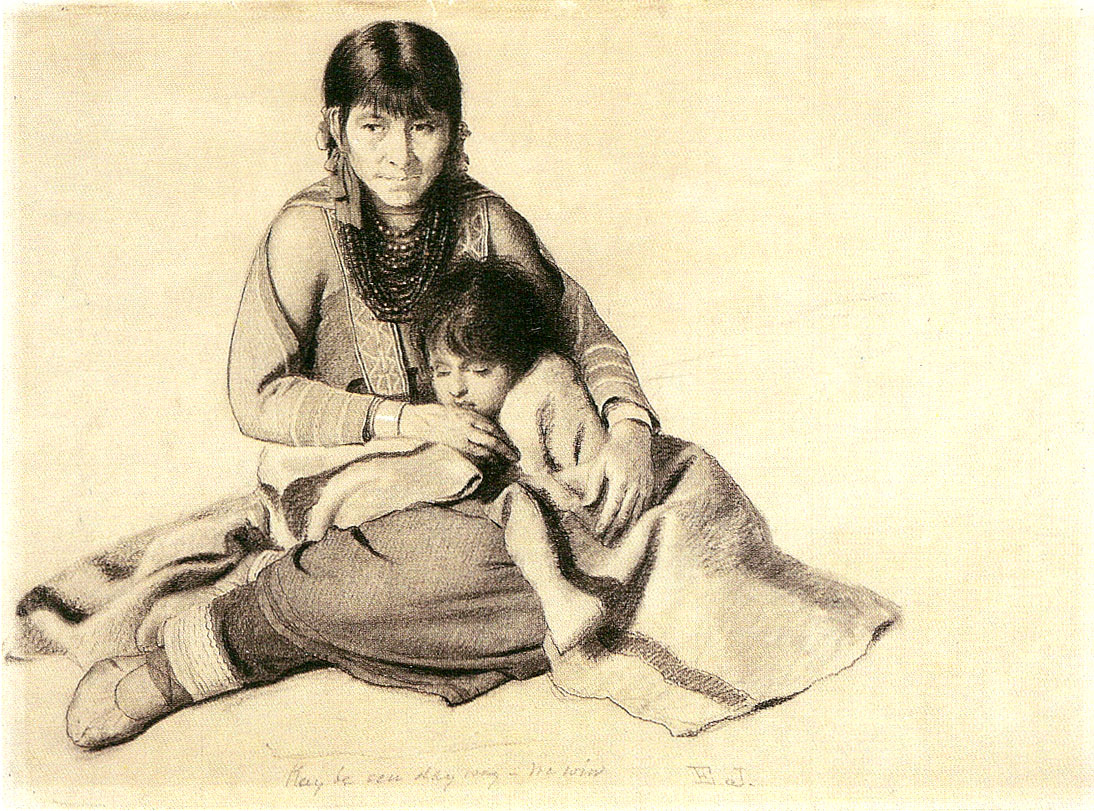

“Why do you always do what those older boys ask of you?” Bolorma Vorov asked as she tended to the cuts and bruises on her son’s body.

“They said they were hungry,” Erdene replied.

“That doesn’t make it right to steal,” she countered. The boy gasped as she used a tincture of iodine to disinfect a nasty cut just below his shoulder blade. “That old coot really got you good this time,” Bolorma grumbled under her breath.

She inspected the damage from the stinging nettle whipping. It looked like it hurt a lot, but her son was a fast healer. All traces would probably be gone by morning. “Try not to get caught next time,” she said.

“He said my legs were too short,” the boy complained, but he smiled at his mother.

Old Gleb had always had it in for Erdene. He called the boy a half-breed on account of his father being Jewish, but out here, everyone was a mutt of some kind. Even the Buryats, the ethnic non-Russian population that lived on the shores of Lake Baikal, were a mixture of Eskimo and Mongolian ancestry. Who was Gleb to call Bolorma’s little boy a half-breed?

Bolorma had witnessed the population grow and change over the years. She had been living around the sacred lake for almost half a century, ever since she woke up broken in the fallen forest on the bank of the Tunguska River.

Bolorma didn’t remember herself before then. She didn’t even know how old she was. She looked like a woman in her twenties, but she knew that wasn’t true. She was just slow to show signs of aging. But she had learned long ago that people were scared of strange things–and being slow to age was strange indeed–so she’d moved around the region a lot, staying in any one village for no more than a few years.

She had thought she was too old on the inside to have babies—or too broken—but now, here was Erdene. She hugged her boy gently, trying not to put any pressure on the wounds caused by Gleb’s stupid head and angry heart.

She hated to see her son abused, but he had to make his own way. She worked all day at the prison camp, and Erdene wasn’t allowed to join her on the grounds. When Ira was transferred to the fish factory gulag, she had come with him in hopes of finding work nearby. The factory had an unexpected opening for a cook, and Bolorma got the job. Now there was always food for her and her son, and she was usually able to ensure that Ira got enough to eat as well. It was a good job. But during the day, Erdene was in the loose care of the two old women from the village who rented Bolorma and Erdene a room in their log house. It wasn’t much, but Erdene had a roof over his head, and the women did keep an eye on him—at least, when he was somewhere their eyes could see. Unfortunately, Erdene wandered.

“Mom?” Erdene perked up. His back looked better already—the skin practically healed before Bolorma’s eyes. It was another thing she had learned to keep quiet about; no one else healed like that around here. She was grateful for her blessings, but she knew it was wise to keep them well hidden. No one liked people who were special.

“Yes, child?”

“There was a man and a woman out by the docks. They weren’t from around here.”

“I heard about them,” Bolorma said. Everyone heard about everything around here.

“The man, he stopped the old coot—”

“Be nice, Erdene.”

“Gleb Gregorivich,” Erdene corrected himself, but he made a face to show he still thought the man was old and mean. “And you called him that.”

“That doesn’t give you permission to do the same,” Bolorma said. “You’re going to get thrashed again if you add disrespect of elders to your list of crimes.” She took a deep breath. “So, what about these people?”

“I saw them get on a boat,” Erdene said. “And there was a lot of banging about inside. And then there was a very bright light. Bright, like the sun, but bubbly.”

“Bubbly?” That got Bolorma’s attention. As far as she knew, Erdene didn’t have the magic senses she had. Bolorma could taste movements and hear music in smells. It was one of the reasons she was a good cook–she danced as she made food, and it always tasted better than the ingredients she started with. But as much as she had tried to teach him to do the same, Erdene had displayed only ordinary perception. There was no magic in his ears, or eyes, or tongue, or any other part of his body as far as she could tell. It made her sad. But at least he possessed the magic healing; that was more important than food music anyway.

“When you say bubbly, Erdene, do you see light bubbles? Like sun bunnies?” When the trees were full of leaves in the summer, the sun streamed through the patchwork of holes in the canopy and made circles of sunlight below–sun bunnies. Bolorma sometimes made them with her long black hair, and she had taught Erdene how to make them by interlacing his fingers and leaving little gaps in between. Once, during a partial solar eclipse, the sun bunnies each had a bite taken out of them—thousands of tiny images of the crescent sun.

“No, not like sun bunnies,” Erdene said. “For a moment, when the light was the brightest, I could feel it on my skin, and it felt like bubbles in a brook. Little tiny bubbles just popping all over my hands and back and face.”

“So you couldn’t see the bubbles?”

“No, I just could feel them,” he said. “And then they were gone, and the light was gone. And there was no more sound coming from the boat. I waited and waited to see if it would happen again, but then I saw the old… Gleb Gregorivich, so I ran home.”

Bolorma considered her son’s story. He’d always had stories for her: a shaman riding the wind, or a colorful bit of cloth tying itself around the sacred posts out by Three Brothers Rock, or a large seal–an old nerpa–giving him a gift of fish for dinner. Were the stories true? Bolorma liked when the nerpa’s gifts were enough for a good fish stew. But there probably wasn’t a magical fish-granting seal, and her boy was just covering up a theft.

She lay her son down in the bed. Even though it was still early, it was already cold and dark. This was March, and winter was still ever-present. As she pulled the blanket over her son, Bolorma took another peek at his back—it was completely healed now. That was exceptional, even given their blessing of fast healing.

“Tell me if you feel the white bubble light again,” she said as she tucked the blanket around him.

Tomorrow, she decided, she would check on these visitors for herself.

***

URT Space

“How did it go?” Asa asked Paris and Angie as they stepped inside the vestibule. The rest of the Urgent Response Team–the URTs–were there to greet them.

The vestibule, connecting the URT’s space with the Earth simulation, was shaped like a long, meandering corridor. It was white all over, with white light permeating every corner and every turn. Next to the door through which Paris and Angie had just returned, there were two screens, both showing the inside of the boat cabin–a dark, wooden space with a locked door and a small round window, also locked. It all looked secure.

“We saw the boy,” Angie said. The white light of the vestibule felt effervescent on her skin. It was programmed to cleanse and heal any injuries sustained during the outing into the simulation, and it also gave an energy boost to the tired bodies of inter-world travelers. Angie immediately felt better, the simulation immersion sickness–the SIS–completely gone.

“For our second outing among humans–” Asa started, but Paris cut him off.

“The kid was being beaten. We barely got there in time.” Paris’s voice broke as he spoke. “And Bolorma wasn’t where you said she’d be,” he said angrily to Haskalah, who was in charge of getting location data for all of the survivors.

Haskalah recoiled from the venom in Paris’s voice, stepping back behind the other members of the team.

“Paris.” Asa put his hand on Paris’s shoulder. As the socio-psychologist, Asa was in charge of supporting the emotional needs of his people. “This is all new to us; we’re all trying,” he said, trying to calm the situation with his voice as well as his words. Paris could put other team members in danger if he couldn’t control himself out there in the Earth simulation; his raging emotions needed to be kept in check. “She must have been close if you found the boy right there,” Asa added.

“He knows, Asa,” Angie interceded. “It’s just that it was so physical, so raw. It’s one thing to look at the vids, but being right there… it felt so real.” She struggled to communicate the overwhelming power of being immersed in a simulation after the decades spent within the confines of their bland existence between worlds. It had been so long since any of them had been inside a world that felt genuine. “And the boy, he got hit so hard.” Angie shivered at the memory of bright red blood bursting from Erdene’s back.

“They’re savages,” Paris spat. He knew he had to master his emotions, but he was finding it hard. After years of watching Bolorma survive in that godforsaken wilderness, feeling helpless as she was brutalized by both man and nature, Paris had hoped he would finally be able to see his mate with his own eyes, to hear her voice, to touch her skin, her hair. Instead, he’d had to watch the son of the woman he loved being abused by some loathsome specimen. It was sickening.

Everyone understood why Paris was explosive when it came to Bolorma. For their people, the mating bond was more than an emotion. It permanently fused the lovers’ souls together. When a couple was together, the bond suppressed physical pain and augmented strength and endurance. It increased the couple’s chances of surviving a crisis. But when the couple was stressed by physical separation, the bond was hard to handle. Distance and threat of danger made rational thinking almost impossible; one mate would do anything to save the other. Some described the sensation as having their chests ripped open.

Asa could only imagine how painful it was for Paris. Without the physical proximity of his mate, Paris was undergoing constant torture.

Bolorma, on the other hand, was spared the pain. She was completely oblivious to the mating bond connection, which, for her, had been severed by the blast almost half a century ago.

Asa watched Paris closely, noting his elevated blood pressure, labored breathing, and racing heart rate. Paris was going to be particularly difficult to deal with, both emotionally and physically.

“Did you feel her? Did the bond work?” Asa asked in soothing tones. He had to know.

Paris didn’t answer right away. He tried to collect himself. He knew he was acting badly, but it was so difficult to keep it together when he thought of Bolorma’s son being been beaten right in front of him. He took another couple of deep breaths and emptied his mind of the image. He took almost a full minute to compose himself, and the others didn’t rush him.

“I’m sorry, Haskalah,” he said at last.

“It’s fine, Paris,” Haskalah replied, but didn’t move any closer. “I have some ideas. We can work on them together if you like.”

Like Paris and Bolorma, Haskalah was a coder–his job was to create and manipulate the simulation, and to program the resources the team needed to survive both here and out there.

“Yes. I’d like to do that as soon as possible,” Paris replied, now almost in full control of himself. He didn’t really blame Haskalah for not finding Bolorma; he understood the difficulties of locking a person down in space and time within the simulation. It had just been his frustration talking.

“We can start right away,” Haskalah offered brightly.

Paris started to move, but Asa stopped him from walking away. “Paris, did you feel the bond?” he asked again.

“I… I felt a connection to the boy,” Paris finally answered. “It wasn’t very strong, but I felt it. That’s not normal, is it?”

“Perhaps it is within this simulation,” Asa offered.

“I don’t know,” Angie said. Asa glared at her, but she ignored him and continued. “We don’t have a way of making extra souls here. Back home, Erdene would have been born with a fully developed unique consciousness. But here on Earth? Since we are not of this world, how would that work? Perhaps part of Bolorma’s soul was fragmented into her son? That would be my guess.”

“That might explain why my connection to Bolorma is more tenuous,” Paris said. “It feels different than before. But why would it feel different now, rather than when the child was born?”

“Perhaps she and the boy were physically closer together before?” Angie speculated. “Bolorma carried Erdene with her everywhere for the first three years. And before that, she was pregnant, so they were together that way. It is only in the last year or so that Erdene has been more independent. And even then, they are still together a lot. You might not have been able to pick up on the distance between them from here, outside of their space.”

“If that is true, it would mean that I am losing Bolorma,” Paris said, a slight quiver in his voice. “Even more than before. More than I thought.”

“She’s still there, Paris. And the biggest part of her is still here with us. Someday, we’ll be able to fuse her soul together again,” Asa said.

Asa took Paris by the arm and gently guided him out of the vestibule and back to their settlement. The rest of the team followed, but they gave Paris and Asa plenty of room.

***

The URTs were a team of scientists who had tried but failed to protect their own simulation after the Great Revelation–that terrible destructive realization that nothing was real and that everything, and everyone, was nothing more than computer sprites. Before their world was destroyed, along with the millions of souls within it, the team had managed to escape, surviving their simulation’s destruction in a tiny crack they had carved out in the virtual space between the millions of other simulations.

The URTs—the twenty-seven who had survived–then looked for another simulation where they could fit in unnoticed and live out their lives as refugees. They all agreed on the characteristics they wanted for their new home. For starters, they wanted their technology to give them an advantage, so the simulated civilization had to be less advanced than their own; but they also had a fondness for indoor plumbing, so they weren’t interested in simulations stuck in the Dark Ages. They agreed that the dominant intelligent species had to be on top of the food chain–it was no fun being eaten by a predator–and that this species had to be an air-breathing land dweller with senses intuitive to the URTs: vision, hearing, touch. The species also had to be able to build things. Finally, they wanted a world that wasn’t on the verge of its own Great Revelation. They had just witnessed the destruction of their own civilization and couldn’t bear to face another similar catastrophe.

After reviewing thousands of simulations, they finally decided on Earth. It fit their criteria well. But one feature of Earth was unexpectedly new to the URTs: Earth had an excess of governments, races, languages, and religions. The URTs’ world, like most of the other simulations, was made of one people with one set of beliefs, one language, and one government. Some of the other simulations the URTs had encountered had different species competing for dominance, but Earth was the only one where the single dominant species was broken into so many different factions. But this wasn’t necessarily a problem; the URTs reasoned that, if the Earth did have to face the Great Revelation, perhaps its diversity would help protect it. Perhaps the monoculture of the URTs’ world had contributed to its downfall.

Even in their exile, the URTs kept their familiar social structures. They worked in triads and found them critically important. Like legs of a tripod, each member of a triad was carefully chosen to balance and support the others. Each member contributed their own unique, complementary skills and perspective to a problem, thus increasing the chances for a successful resolution. Apart from the mating bonds, these work triads were the most stable social structures of their world. And while triads would sometimes split to allow members to move on to different projects, usually work triads remained together for life.

Not that any of that really mattered now—seeing as only fourteen survivors were left.

Originally, the triad of Sekhel, Gibbor, and Zonah was in charge of creating bodies. Before they could attempt to break through into the Earth simulation, the URTs needed to design and program human bodies that they could use to store their own consciousnesses while visiting a foreign simulation. But after a decade of work, they still hadn’t come up with a way to stuff an URT’s entire consciousness into a human form. It was like trying to cram a feather mattress into a suitcase: no matter how much they managed to stuff in, there was always some left over.

If they’d had more time—perhaps another thirty years or so—they felt they could have solved the problem. But no one wanted to wait that long. So Gibbor came up with a radical solution: to split an individual consciousness between two vessels, and construct a programmatic link between them. The human body held about half, and the other half was held inside the Alpha body, now immobile and stored within the URTs’ inter-simulation space. By linking the two together, the URT member in the human body could seem to be whole… at least for a while.

Gibbor’s triad started with a few Earth body types–nothing too flashy, just practical construction and hard-to-identify racial features to fit into the Eurasian part of the world, which was climatically similar to the URTs’ world. They created seven archetypal body forms: an old man and an old woman, a middle-aged man and woman, a young man and even younger woman, and a very young girl. They could make small adjustments within each body type, so none of the URTs looked identical to the others. But there was one distinctive feature that all the bodies shared: vivid emerald green eyes. Sekhel liked that shade of green.

Paris worked closely with the triad developing and programming the body types. He had a knack for adjusting easily to different bodies–quickly adapting to their different physical characteristics–so he acted as a test pilot. Out of the seven forms created by the triad, Paris ended up with three of them for his own use: an old man, a young man, and a very young girl. Bolorma had approved of the young man for its sexiness and vitality, but Paris could choose any one of his three forms for his outings on Earth. The rest of the URTs each had only one human body form they could use out in the simulation.

Unfortunately none of the Earthling bodies worked all that well yet–they were just prototypes. Gibbor’s triad expected to spend many more years perfecting them, so each of the URTs chose their first Earthling body knowing that they could change to another when selecting their permanent form.

Bolorma wasn’t very good at body swapping, and she wanted something permanent right off. She chose the body of a beautiful fifteen-year-old girl. Paris had approved it, of course. Once fully integrated into the Earth time stream, the bodies would start to age, albeit very slowly. Being young at the start would allow Paris and Bolorma to have a large family. They both wanted a lot of children.

Angie chose the same body, with adjustments. Like Bolorma, Angie was terrible at adapting to dissimilar human forms. She was hopelessly awkward with adjusting to different heights, weights, and physical abilities. It was already hard enough to get used to a new Earth body–she didn’t want to worry about switching between different models, too. And she wanted to be a beautiful young woman. Very beautiful. Angie liked being the center of attention.

For her first body, Asa chose the form of a middle-aged man. The body was designed to be forgettable–your basic boring body type–to more easily blend in. Plus, males seemed to have additional privileges in this world’s simulation. Later, Asa figured, she would pick something more appropriate. No rush.

While Gibbor’s triad worked on developing the Earth bodies, the triad of Haskalah, Chapar, and Khulan–the triad that had created the crack that had allowed the URTs to escape from their own failing world–was in charge of breaching the Earth simulation barrier. The simulation barrier was analogous to the surface tension that separated water droplets from each other. It was necessary to precisely match the conditions of the simulation in order to allow a vehicle to enter the Earth simulation without disturbing it too much.

When the URTs made their escape from their own simulation, they’d only needed to break though one such barrier, and it hadn’t mattered much what they left behind in their wake–their whole world was in the process of collapsing anyway. But now that they were safely in their crack between simulated universes, the URTs had to be more careful, both to preserve their tiny space as well as not to damage their potential new home.

For many decades, the URTs were limited to just observing the Earth and its inhabitants. But there was nothing like a hands-on experience when it came to really understanding the laws and the driving forces behind a simulation. So when the bodies were ready, the URTs planned a visit.

The first visit to Earth was to be purely exploratory, avoiding any interactions with humans. The URTs picked a remote location in Siberia, near the Stony Tunguska River, far from any human settlements. On that visit, the goal was to ensure that the newly designed bodies worked properly in the simulation, creating a template for future adjustments and improvements to the prototypes. After that, each URT member would pick the permanent body that they wanted to settle in as refugees to Earth.

The subsequent visits to Earth were to be lasting. In their new bodies, the URTs would disband, each to their own chosen location on Earth, and they would try to live out their lives as refugees. They hoped to blend in and live in harmony with the people of Earth.

Nineteen of the twenty-seven survivors decided to participate in the first visit to the Earth simulation. They were anxious to try out the bodies they had created, and they wanted to be the first to explore the new world in person. They called it “stretching their legs,” which was an inside joke–their Alpha bodies didn’t exactly have appendages that could be called legs. Haskalah stayed behind to monitor the simulation, while his triad partners, Chapar and Khulan, joined the expedition. Zonah also stayed behind while her triad partners, Sekhel and Gibbor, went. They were leaving for just an hour–two at most.

Those who stayed behind watched anxiously on the vids. It felt like a party, a celebration of a new beginning, a new life in a new world. It would be glorious, they all believed.

Their craft broke through into the simulation in the early morning hours of June 30, 1908.

And right away, it was obvious that something was wrong.

An anguish-filled wail echoed around them, coming from the Alpha bodies of the explorers–and a moment later, there was a blast. The URT members left behind could only watch as mature trees were flattened to the ground in a circular pattern all around the blast site. Altogether, two thousand square kilometers of forest were affected. The Tunguska Blast–as it became known to the inhabitants of Earth–had unleashed energy equivalent to that of an atomic bomb.

Eleven of the URT explorers died instantly. The partial souls in their Earth bodies were extinguished, and with them, the Alpha bodies they left behind were also killed. The other eight survived the initial explosion, but the links to their Alphas were shattered, and they forgot who they were.

Within days, two more survivors were lost. While they were able to heal themselves of physical injuries, the shock of fractured consciousness proved too much to overcome.

And thus, after a week, only six remained in the Earth simulation: Bolorma, Sekhel, Gibbor, Naran, Gerel, and Adamah. These survivors had no way to get back, nor even any memory of where they had come from. And the eight URTs who had stayed behind in the crack between simulations had no way to mount a rescue operation.

Out of the millions of souls of a once-great civilization, only fourteen individuals were left.

***

After the blast, the eight who had remained outside of the simulated worlds did their best to protect their six comrades trapped on Earth. The vids–passive taps into the simulation–allowed them to watch what was happening, but they had no power to intervene directly, so they could only look on helplessly as their comrades struggled, enduring hunger, injury, and loss.

It took decades before the URTs found a way to manipulate the Earth simulation without actually entering it–and even then, their influence was very limited. They could use their ability to give small advantages to their stranded people–a nudge here and there to improve their lives in an alien world. At times, they were able to provide money, information, and other resources. They created papers–title or wills which endowed their people with the tools they needed to survive. And occasionally the URTs smoothed relationships with the local authorities and bureaucracies if there was trouble. They even set up advantageous meetings with Earth’s powerful and influential, who could provide direct assistance. The URTs encouraged, prodded, and manipulated everyone into rendering help to their people.

The URT survivors on Earth knew about none of this. Most of them simply felt lucky. What they didn’t know was that this “luck” took a lot of behind the scenes work by the rest of the team.

But it was agonizing for the remaining URTs to be unable to do more for their stranded friends. And they needed to do more. For one thing, the survivors’ bodies were just prototypes and didn’t work perfectly yet. In their little inter-simulation niche, the URTs were practically immortal; death was a programmed phenomenon, coded into the matrix of the virtual world. But death was all too real inside the Earth simulation and for the URTs trapped within. In the absence of regular repairs–resets to the original designed specs—the survivors’ bodies would be damaged over time, and their occupants killed.

Of all of the survivors, Bolorma proved to be in the most danger over the years. She had chosen the body of a beautiful young female, which proved to be a fraught choice in rural Siberia at the turn of the twentieth century. After the explosion, she had been sexually assaulted and sold into marriage–a horrific experience. Her first child, who would have been the first true hybrid between their worlds, died. Paris forced himself to watch all of it, even as he was unable to do anything to prevent it.

And Bolorma was the most difficult to nudge. She was stubborn. She refused most of the little lucky breaks and coincidences that Paris created for her in his attempt to get her out of rural Siberia and someplace a bit more civilized. She made the decision to stay in the cold wilderness, where she became a bone-carving artist, and a well-regarded one at that.

Bolorma met Ira Vorov on a railroad gang. Paris was still not sure how it happened that she fell in love with that man, but he knew she had no memory of Paris. She was free of their bond, and she was young, beautiful, and talented. How could any man resist her?

Others fared better. Immediately after the blast, Sekhel and Adamah found each other and survived together. Sekhel had chosen the body of an old man, and Adamah the body of an old woman. After their Earth bodies healed, they traveled out of Siberia, through Mongolia and China, to eventually settle in Tokyo.

There, Sekhel discovered Zenyoji Temple, built for a sacred six-hundred-year-old pine tree, Yogo-no-matsu. He settled down as a monk. Adamah worked at the temple as a healer. Of course, neither had knowledge of their true selves. The other URTs could only watch as they struggled and starved in war-torn Tokyo. But both survived World War II, and they were safe where they were for now.

Like Bolorma, Sekhel lost the connection to her mating bond. The bond still existed, but the fraction of her consciousness that contained the bond stayed back in her Alpha body. Gibbor, unfortunately, felt his bond to Sekhel all too well, even if he had lost his memory of her. But his strong attraction to an old male monk was just not manageable in the world of Earth cultures in the first part of the twentieth century. So he chose to move as far from Sekhel as possible, to try to suppress the strong attraction he felt. He reached London–a dangerous place during the world wars–and became a distinguished gentleman of undetermined age, working as a revered scientist and inventor at the Museum of Natural History.

Naran and Gerel took different paths after the blast. Naran ended up as a mathematician in Vladivostok at the southeast tip of Russia. Gerel made her way west to France and settled into a rural community about fifty miles from Paris.

In addition to nudging events on Earth to help these scattered survivors there, the URTs outside the simulation tried to find a way to one day successfully extract their friends—or to join them in the Earth simulation safely.

Unfortunately, the Tunguska accident had destroyed all but one of the URTs’ working triads. Without Sekhel and Gibbor, Zonah was left to work alone, and she was overwhelmed with the task of trying to fix the Earth bodies. Haskalah, the only surviving member of his triad, had the same problem, but his situation was made worse by the fact that he felt he was responsible for the blast in the first place–so not only was he alone, he was also crushed by guilt. He threw himself into his work, laboring for years to try to come up with a safer approach to break into the Earth simulation, and rebuffing any offers of help.

Eventually, Haskalah succeeded and created the vestibule, a virtual structure acting as a bridge between their crack between worlds and the Earth. From this vestibule, Haskalah could cut a slit into the Earth simulation without a need to match variables between their space and that of Earth. For his first test of the technology, he insisted on being alone, with the others back in the safety of inter-simulation space. Only after he had succeeded did he allow the others to venture into the Earth world.

And so the URTs started traveling to Earth. At first they had only temporary slits, just a tear in spacetime, which would disappear after use. Paris’s stacking pyramid of luggage helped stabilize these slits, creating a temporary door into the new world. Later on, the URTs created permanent doors—stable passages between the vestibule and fixed geographic locations in the Earth simulation. From within the vestibule, such doors could be right next to each other, yet would open to different continents on Earth. It was a perfect, instantaneous discrete point transport system.

Access into the Earth simulation was just the first step. Now the URTs had to solve the body problem and fix the split consciousness. Both were required to save their friends trapped in the alien simulation, and both were necessary if the URTs were ever to become refugees of their civilization on Earth.

Chapter 2: The Funerals

Sunday, January 4, 2009

Zenyoji Temple, Tokyo, Japan

I stood holding hands with Paris. I knew she wasn’t really a cute seven-year-old girl with long pigtails and giant green eyes–that was just the body he was using at the moment. Paris had several bodies for his trips into our world–although he had one less now. The body of the old man, Mr. Lee, had been stolen from him by the Others, and now he was dead. Well, the body was dead; Paris was still very much alive.

In fact, that was why we were all gathered here in this damp graveyard: to bury one of Paris’s bodies, the body of an old monk. It was a body I had known since I was a baby–the body of Mr. Lee, who lived in our building and ran a fake-o travel agency while secretly keeping an eye on my family: Erdene and Eve Vorov, my parents; Julie, my older sister; and my grandmother, Babushka Bo.

“Are you okay, Peter?” Paris the little girl asked. We were placed a bit to the side, in the “kids’ section” of the funeral held at Zenyoji Temple.

I just squeezed her small fingers in answer–it felt awkward to speak during the ceremony even if I didn’t understand a word of it. My Japanese was rather non-existent. But I knew we were all saying goodbye to the many monks who were killed in the carnage caused by the Others.

Gibbor was standing close to us. He was the real reason I was here in Tokyo, attending this funeral. Joseph Gibbor Svetovich the Third, as he liked to call himself, was another survivor of the Tunguska Blast, just like my grandmother. And he was having medical problems, just like my grandmother did. I knew his memories had been fractured in that blast a century ago–half staying with him in his Earth body, the other half getting stuck back in that other space the URTs had created outside of our world. My grandmother Bo, short for Bolorma, was split in the same way–and she died when her soul got too confused. Or at least, that’s how Paris explained it. The same thing had happened to all the other members of the URT original landing party. Of that group of survivors, only Gibbor still lived.

The URTs had offered to attach my soul to Gibbor’s–to some extra portion of his consciousness that didn’t fit into his Earth self. They had done the same procedure with my sister Julie–attaching her soul to my grandmother’s. Now she was more than just human. Now she had skills! And if I were to attach my soul to Gibbor’s, I’d have those skills too. Not only would I know what Gibbor used to know–or at least what was hidden in his memories that were not part of the Earth-bound Gibbor–I would also be able to use URT technologies.

Unfortunately, I would only take in Gibbor’s extended self once his Earthbound body died. It wasn’t a gift, it was an inheritance. It was the same with Julie–her changes occurred after Babushka Bo died. And from what I’d seen so far, Julie had gotten the best inheritance anyone could ever hope for. Don’t get me wrong–I missed my grandmother a lot. But because of the Julie-Bolorma soul fusion, she wasn’t all gone, not completely. Part of her lived on in Julie. She wasn’t dead dead. And Gibbor wouldn’t be dead dead either, not if I had part of him in me.

I thought it was an excellent plan. And my dad wanted me to do this soul bonding, too. Frankly, I thought my dad would have preferred it was him, but the URTs told him he was just too old to accept additional mental stuff. I was only eleven–well, eleven in a few weeks–so my brain still had the necessary plasticity, as the URTs explained, to accommodate the extra baggage, even exotic baggage like Gibbor’s half-consciousness.

So technically, the real reason I was in Tokyo was to check out how much I liked Gibbor. But now there were also these funerals to attend…

That’s funerals with an “s”–almost a dozen monks died after the Others used Paris’s body to rampage through Zenyoji Temple–a temple dedicated to an ancient pine tree. Three of the funerals were for URT members: Sekhel, Adamah, and Mr. Lee. Of course, Mr. Lee was actually Paris, and Paris was still standing next to me in his little girl body, holding my hand. But Sekhel and Adamah were dead. Gone. Confusing, I know.

Babushka Bo’s funeral was only a week earlier. I had never been around so much death in my life–I was only ten, after all. And now I was waiting for Gibbor to die. I wasn’t sure how I was supposed to feel about all this. All morning my parents had been giving me looks of concern.

Oh, and something had happened between Julie and Paris. I didn’t know what yet–they didn’t tell me everything. But I always knew more than they thought I did.

For instance, I knew Mr. Lee was Paris before anyone else in my family did. Maybe because I’d spent more time with Mr. Lee than the others did. When Paris was Mr. Lee and I was just a little kid, he would go to the park with Babushka Bo and me. He taught me the names of different plants and rocks. And when I showed an interest in natural history, he started to bring me cool rocks and specimens from all over the world.

Mr. Lee even went on field trips with my elementary school; whenever my grandmother came, he came too. He was a real interesting person, and he treated me like I was an interesting person too, not just some kid.

So when the URTs pretended to move into our apartment building, posing as a single dad with two young daughters–Asa Urt, Angie Urt, and a little girl named Paris Urt–I recognized Mr. Lee in Paris. Well, not right away–but eventually. Paris was Paris, and it didn’t matter what body he decided to use.

Now I stood with Paris–young, little girl Paris–waiting for Mr. Lee’s funeral to be over. It was raining, of course–it always rains during funerals, right? Gibbor had this giant black umbrella, and Paris and I huddled next to him when the rain got stronger. Paris cried. I knew she wasn’t crying for her own body–that would have been too weird. She was crying because the other people who were killed were like her family. She said it was her fault. But it wasn’t–her body had been stolen and used as a murder weapon. Not her fault!

I wanted to make her feel better. When Paris was in the body of a little girl, it was hard not to feel super protective toward her. That was the weird part about body swapping–how much your feelings toward the person changed depending on how they looked. I guess we humans are still a very backward people.

Of course, I was not all human. I was the grandson of Bolorma Urt. That made me a quarter URT. And soon, I’d be much more than that.

Angie wasn’t at the funeral. She should have been, but she wasn’t. It was strange, and I noticed. I asked Paris about Angie, but she just brushed me off; that was very uncharacteristic of her. Gibbor wouldn’t tell me anything either, but he might not have known what it was all about. And Asa was a typical adult–he deflected my questions and told me we would talk later. I knew that Angie’s absence was bad, I just didn’t know in which way it was bad.

My sister was another person who should have been at the funeral and wasn’t. I was told that she had managed to save Paris after an epic battle in some geometric prison–again, the details I’d gotten were very hazy–and now she was just too tired to attend. That didn’t make sense to me. I had just flown to Tokyo from San Francisco, which was a very long flight, and I was exhausted, but I still had to go to the funeral. Julie could just step through a transport portal door and she’d be here, no mundane human travel necessary. It was weird that she didn’t.

The funerals were conducted in Japanese, and I don’t speak Japanese. But sometimes language can be a distraction. Without understanding what was being said, I could focus on what was important: body language. For instance, I saw that my dad repeatedly looked over at Paris in a funny way–bad funny. Paris was crying, but my dad’s expression wasn’t sympathetic, but angry. And I caught Paris glancing back at my dad and then hiding from him behind me. Meanwhile, Asa kept looking back and forth between my parents and Paris–back and forth, back and forth.

Something was going on that had nothing to do with the funerals, that’s all I’m saying.

Angie did show up toward the end. She walked up directly behind Asa and pulled him off to the side. And they talked. I haven’t been to a lot of funerals, but I knew you’re not supposed to do that. She kept glancing over at Paris. When she motioned for Paris to join them, I came as well, and Paris didn’t try to stop me.

“I couldn’t find Julie,” Angie said. She was always direct. No point in wasting words.

“She didn’t return to the lab?” Paris asked. After the prison experience, everyone assumed Julie needed a bit of extra-worldly medical attention. Inside the vestibule, a space that connected our world with the space they programmed for themselves after their world ended, the URTs had a medical center. Zonah–she wasn’t at the funeral either–was their doctor. Paris said that Zonah had worked on him after Julie rescued him. Paris had been in a bad way after that experience, or so I had been told.

“That’s what I thought. I figured we’d give her some time. But she was very upset with you… with all of us,” Angie said.

“I know. I should have followed her. But I wanted to give her some space,” Paris said.

“Why is Julie angry with you?” I asked. “Why does she need all this space-time?”

But I was ignored as usual.

“Can you feel her?” Asa asked Paris. Now that was interesting–I didn’t know that the URTs could feel each other at a distance. That’s what I mean about being observant: sometimes you can learn things just by listening.

“I don’t know,” Paris said. “Sometimes, it’s like all I can focus on. And sometimes it fades away to almost nothing. I don’t understand it.”

“As Julie absorbs more and more of Bolorma’s consciousness, she changes,” Asa said. “It probably takes time for you to recognize her.” I didn’t understand most of that, but I did hear that the connection to the memories wasn’t instantaneous.

I looked over at Gibbor. He stood with his head down, absorbed in the eulogy for one of the monks. He was fluent in Japanese. I wondered what was stored in Gibbor’s memories. He was a grown man, and I was just a kid. I hoped it wasn’t too X-rated. I was too young for that stuff, but I had to admit that I was interested, in a theoretical kind of way.

“We have to go find her!” Paris spoke louder than she should have, because my dad’s head spun in our direction, and now he was coming over. “She could have walked through any one of the doors,” Paris continued. “And some–”

“You’re talking about my daughter!” Dad broke in. “You told me she was resting. Am I hearing something different now?” My dad was good at getting to the point too.

“We thought Julie would just walk back to the medical center. Zonah was waiting there for her.” Angie was less direct and more diplomatic when she talked to my father. “But now it seems–”

“Now it seems that you don’t know where she is,” my dad finished.

“Yes.”

Dad turned on Paris. “What were you two fighting about this morning?”

Impossibly, Paris shrank to an even smaller size–she looked like a five-year-old. Her big eyes were red and swollen with tears; she was pathetic. But the little-girl thing wasn’t working on Dad. He knew Paris was also Mr. Lee.

“We told you that Bolorma and Paris used to be mates,” Asa said. That was interesting, and it explained a lot, but I didn’t say a word. I was learning to keep my mouth shut. “So when Julie got Bolorma’s partial memories, it seems she also got some of the bond,” Asa continued.

“The bond?” Dad’s voice contained a mixture of anger and anxiety. I recognized it–it was the same voice he used with my teachers when I got in trouble during recess.

“A mating bond,” Asa explained. “Our people mate for life. Bolorma lost her bond to Paris during the Tunguska accident.”

I noticed that he used “accident” instead of “explosion.” Each URT had their own way of talking about their initial breach into our world.

“So what does that mean to my daughter?” When my dad grabbed hold of a topic, there was no shaking him off.

“We believe Julie is experiencing some echoes of that bond,” Asa said.

“Meaning?”

“Meaning it is not appropriate,” Paris said. “I was trying to tell her that we’d extinguish the bond as soon as we figured out how. But Julie rejected that. She wants to keep the bond.”

“I see. And she was so upset that she ran away?”

“We thought she just needed–” Asa tried.

“But you thought wrong, didn’t you?” Dad interrupted. “And now my daughter is missing.” He looked at Asa, Angie, and Paris in turn. Asa nodded dejectedly, cowering under my father’s withering gaze. “How many doors to this world do you have? How many possibilities are we talking about?”

“There are two hundred and eleven doors,” Asa said. That was good to know. “We have doors to most large metropolitan centers.”

“San Francisco, Tokyo…” Dad said.

“Yes. And many more. Paris took Julie to a Hawaii beach house we keep as a little vacation getaway. Julie has also been to Paris.”

“Yes, I knew about that. Is there a possibility my daughter could get hurt in any of these places? Does she know how to get back into this… this…”

“Vestibule,” Angie said helpfully.

“Vestibule,” Dad repeated.

“No. We have tight security measures. Julie won’t be able to get back if she walked outside.”

I noticed Mom had quietly joined us and was listening. She looked even angrier than Dad.

“Then go get her,” Dad said.

“That’s exactly why I was getting Paris,” Angie explained. She took Paris’s small hand and pulled her away.

“I’ll go with them,” Asa told my parents and left in a hurry.

Mom took Dad’s arm and pulled him to follow. She looked like she could chew nails. The funeral service was over by then, so we all walked back in the rain to the little house next to Zenyoji Temple.

Only Gibbor stayed behind.

***

Zenyoji Temple was built around a single ancient pine tree. Back home, we had forests of giant redwood trees tended by park rangers; Zenyoji Temple was just one huge pine tree, tended by a band of Buddhist monks. The tree itself wasn’t very tall, but its branches were very long, and each branch was supported by a custom-fit trellis system like a clutch of crutches, holding up the branches. The tree covered more ground than the actual temple! But it was raining, and everyone was freaked out over Julie’s disappearance, so it wasn’t like I got to see much of this sacred old pine tree.

The URT-owned house was just across the street from the temple, behind a fence enmeshed in a tall hedge, completely invisible from the outside. It was traditional Japanese construction–just like the houses in manga comics. The roof was slanted and the edges were low. The low eaves combined with small windows meant that it was rather dim inside.

But that was just in the outside rooms. The core was entirely different. It was like a spaceship had been camouflaged inside a traditional Japanese shell. The central room had a door that opened to the vestibule–a cool bright white corridor with many doors; two hundred and eleven, as I had just learned–each of them a special shortcut to a different location here on Earth.

If I got my inheritance from Gibbor, I would be able to go into the vestibule and have any injury–any scrape or scar–instantly healed by the prickly white light. I could also use the corridor to travel anywhere on Earth I wanted just by walking through a designated door. Which was apparently what Julie had done–she had run away by walking through one of those doors, creating a big fuss like she always does.

Unfortunately, only the URTs—and now Julie–could safely go into the vestibule. The rest of us, even part-URTs like Dad and me, would die if we tried to step outside of the Earth. Or so I had been told. I wasn’t sure I really believed it, but it seemed stupid to risk dying just to see if the URTs were lying to us.

Within the gleaming light of the vestibule, the big guy, Mattan, gave Asa a hard questioning look. I think he was asking Asa whether my mom should see this stuff; they had always made a point of hiding things from her. Asa made a resigned gesture.

I looked over at my mom, who was staring, transfixed, at the gleaming white corridor. All of a sudden, she had pretty irrefutable evidence that what Erdene had been telling her all this time was true.

“How do you plan on locating my daughter?” Dad asked.

“We were hoping that Paris would be able to feel Julie–” Asa started, but was interrupted by Mom.

“How does this feeling work?” she asked. “From how far away?” The way she said “feeling” made me think she found something creepy about this extra sense. An extra-dimensional link between souls–who comes up with this stuff?

“Well, normally, pair-bonded individuals are aware of each other at all times. But since Julie is not exactly…” Asa seemed very uncomfortable describing the situation. Normally, he acted all confident, but now he was hesitant. He sounded like a Health Ed teacher talking about sex to a group of six graders. Awkward…

Paris was standing behind my back, outright hiding from my parents. I pulled on her hand, and we stepped into another room. “Can you really tell where Julie is?” I asked in a whisper.

“No. I wish I could. I mean, sometimes I can. But it’s confusing. I can feel you and your dad, too.”

“Really? But we’re not pair-bonded, right?” The whole idea was icky.

“No, not like that,” she said reassuringly. But I wasn’t all that reassured. The idea that Paris knew where I was at all times wasn’t very appealing. A guy needs his privacy, know what I’m saying?

“When your dad was born, my connection to Babushka Bo was split,” Paris explained. “I could sense them both. And then when you and your sister were born, there was another shift, and I could feel all four of you. Not well, but–”

“Well enough that playing hide-and-seek with you wouldn’t be fair?” I said. She smiled and nodded. I liked making Paris-the-little-girl smile. “So,” I continued, “you can kind of tell where we are in the world, but not all the time. And now you can’t tell where my sister is?”

“Something like that. When Bolorma died, it all changed again.”

“Can Julie feel you?” I asked.

“Yes. That’s how she found me in that prison.”

“I see. Handy.”

“It was certainly useful at the time.”

“Is it stronger if you’re nearer?” I asked.

“Sometimes. But not necessarily. And it changes over time. We’re planning on finding a way to sever my connection with Julie, but if we didn’t, then it would probably stabilize at some predictable level.”

“With what you’ve got right now, what can you do? If you were in the same room with Jo, would you know?”

“Oh yes. For sure.”

“If she were on the other side of a door?”

“Probably.”

I was thinking of all those doors in their vestibule. “How about the doors in the corridor? Could you feel her and pick the right door?” The Earth was a big place–too big to visit each and every location behind each and every door. But if Paris could guess the right door, it would narrow things down a lot… from two hundred and eleven.

“Maybe, but I don’t think so.”

“How about if you opened each door? Could you go through each one and feel for her?”

“Maybe.” Paris closed her eyes and concentrated hard, squinching her cute face. She was adorable. “That might work. I can open all the doors and walk through each one, just trying to feel if she’s someplace close.”

“That’s it! Go do it!” I was happy I could help them solve this problem. Perhaps they could locate my idiot sister before something bad happened to her. How could one person cause so many problems in such a short time? I could feel my own eyes rolling in frustration.

***

There were only nine members of the Urgent Response Team left. And now Julie, sort of.

It fell to Gibbor to entertain my parents while the rest searched for my sister. He took them into the kitchen to have tea–very British of him. I didn’t like tea, so I stayed in the core talking with Mattan, who was in the vestibule.

Mattan had gone with Julie on the rescue mission for Paris, and something had happened to him. He had passed through a wormhole of wrong-handedness, and now he had a problem with chirality. That’s what he said. Until they figured out if it was safe for him to leave, he was stuck in the vestibule and the other space that the URTs called home.

Mattan was big. I mean, really big. I’d be happy if I grew to be five inches shorter than him, he’s that big. He still sort of looked like Mr. Lee and Gibbor and Asa, if they were all combined together, shaken up, and then given growth hormones. Did I mention Mattan was big?

Mattan sat on the floor of the vestibule in front of the open door to the Tokyo house, while I sat directly across from him. We were each careful to keep our limbs on our respective sides of the divide. It was much easier for me; I wasn’t built like a defensive lineman, if you know what I mean.

“Does your sister do this a lot?” Mattan asked.

“She jumped off a cliff on the Lands End trail,” I volunteered. Jo, I mean Julie, thought it was a big secret, but when you do something as stupid as hiking in the dark on an off-limits portion of the Pacific Ocean trail, you didn’t get to keep it a secret. It was in the newspapers and on Facebook, for goodness’ sake!

“I heard it differently,” Mattan said.

“Really?” It was amazing how information flowed between worlds.

“I think she was pushed,” Mattan said. He looked guilty about it.

“Did you do it?” I asked.

“Oh, no! I would never!” Mattan waved his arms in protest.

“I didn’t think so. I haven’t met an URT I didn’t like yet.” And it was true. They had all been very nice to me. But then people don’t tell me everything.

“Well… you haven’t met Haskalah.”

“You’re saying Haskalah pushed Jo? But he’s out there now, looking for her. Why would he want to hurt Jo?”

“At the time, we didn’t know about the Others,” Mattan said.

He narrowed his eyes at me, like he was trying to figure out how much I knew. I already knew about the Others—the other beings besides the URTs who had managed to break through into Earth from some other world simulation. The Others were responsible for killing the body of Mr. Lee and all those monks. I was told the Others wanted our world, but they didn’t want it occupied. And since I was rather fond of living here–I was rather fond of living, period–I had a problem with that.

“But you managed to password-protect Earth, right? We’re good now?” With all that was going on, I wasn’t up on the latest details of the plan to contain the Others.

“Haskalah worked on that. No one else can break through now,” Mattan said. But he still had that guilty look.

I had made a decision to learn as much about the URTs as I could. They were my special study, now that I was betting my soul on them. And one thing I had learned was that the URTs were sometimes deceptive–which meant I needed to know when I was being lied to. Unfortunately, Asa and Angie were very hard to read. Paris the little girl was easy—she fidgeted when she fibbed. I wasn’t sure what Mattan’s tell was yet.

“No one no one?” I asked.

Mattan looked uncomfortable. He squirmed and scratched his shoulders and shins. It was sort of comical on a body like Mattan’s, but given the subject matter, I wasn’t laughing.

“What are you not telling me?” I asked.

“No one else can break through,” Mattan said. “But… if any of the Others are already here… then they are locked in with us.”

“Here on Earth with us?”

“Yes.” At least Mattan didn’t lie.

“Do you know how many are stuck here with us?”

“No idea. We’re not even sure we know how to find your sister.” He didn’t pull any punches. It was like he’d said, Yes, we URTs are feeble, and you’ve bet the safety of your entire world on us!

“Hmm,” I said. I was thinking about my computer games. Those programs knew where all the characters were and what they were doing at all times. So if our world was a computer simulation, that sort of knowledge would be part of its program, wouldn’t it? The computer would have to know. “Do you always know the locations of all of your team members?” I asked.

“We keep track of our people pretty well,” Mattan said, but it was clear he was hedging.

“How well?”

“Well, we believe in privacy,” he said. “We live in a really small space. Privacy is really a matter of not looking, rather than some technical thing.”

“So you just pretend not to see each other?” I asked.

“It’s not pretending. It’s not noticing on purpose.”

“How very civilized of you. Babushka Bo used to tell me it wasn’t polite to notice when people… passed gas.”

“She was a very civilized woman,” Mattan agreed. “And that’s especially important in a group our size; there aren’t many of us, you know. It’s easy to get to the point where everyone knows everyone else’s business, and that can destroy a group. It was one of the reasons we let Paris keep his dealings with your family private.”

I thought about it. Jonathan Shu, my best friend, used to go to a big public school with me, but now he was going to a small private school and hated it. You fart and everyone knows about it, he’d told me once. “So privacy is a protective thing?” I asked.

“It was one of the problems we had back on our world,” Mattan told me. “Our world was much smaller than yours. Asa called our society a ‘monoculture’–we were all of a type.”

“A type of what?” I asked.

“Similar looks, similar beliefs, similar thoughts.”

“Sounds boring.”

Mattan laughed. “Maybe a bit, when you compare it to how wild the Earth is. But the real problem with monocultures is that they’re less resilient to disaster. Think of agriculture–you’ve studied farming, right?”

“No. San Francisco kids don’t farm.” We really don’t, unless you’re talking about playing Farmville–which wasn’t my game anyway. “But I know what you mean,” I said. “Dad told me about the pest problem with bananas.”

“There’s a banana shortage?” Mattan looked surprised.

“No, not a shortage, exactly. But Dad says that years ago, bananas tasted better than they do now. That banana species got wiped out by some insect or fungus or something, so all over the world, people started to grow another species capable of resisting the pest. That’s the species we eat now. Cavendish, I think? Anyway, now there’s another blight, and it’s wiping out all the Cavendish bananas, too. If they don’t find a way to destroy the blight–or come up with another banana species that’s resistant to it—that’s it for bananas,” I said. “You were like the one banana world?”

“An interesting analogy,” Mattan said. “Angie explained to you about the Great Revelation?”

“Obviously.” I felt my eyes rolling again. It was a Jo move, but it seemed appropriate here. And she didn’t have a monopoly on eye rolls anyway.

Mattan laughed. But it was a sad kind of laugh.

“So you think our diversity will protect us from the Great Revelation?” I asked.

“Asa thinks so.”

“And what do you think?”

“I don’t know,” he said honestly. I liked this guy.

“So about knowing the location of your people…” I bet he thought I had forgotten about it. People always think that if you’re a kid, you must be feeble-minded.

Mattan looked uncomfortable. It might have been that he was just cramped from sitting on the floor, but it seemed to me that it was more than that. “Locating our people on Earth is difficult,” he said. “But after the blast, we had to keep track of the survivors. We learned a few things that might help us find Jo, too.”

“So.” I took a deep breath. “How long do you think it will take to find her?”

Mattan reached down and put his left hand right into the white floor of the vestibule. His fingers completely disappeared under the surface. It was like the floor had become non-solid just under his fingers–like he literally plugged himself in.

“Cool!” I said. I couldn’t help it.

“She’s in Siberia,” he said. His face had a faraway I’m-not-really-here look.

“Really?”

“Unfortunately, she left the little shelter we built there.”

“But it’s really cold there, right?” I couldn’t believe how stupid my sister could be when she wanted to act out. Life wasn’t like a video game. Oh, wait–life might be exactly like a video game. Still, you only get one life–I was almost certain about that. “Is she going to be okay?”

“She’s been out in the snow for a while. But as long as we find her alive, we can fix her,” Mattan reassured me. He had a lot to learn about reassuring humans.

“Don’t say anything about Jo being near death to my mom, okay?” She wouldn’t take that well at all. Not at all.

“Asa is saying that Paris can feel her again,” Mattan said. His face still had that faraway look.

“That’s good, right?”

“Yes, very good. She’s alive, and I think they’ve located her. They’ll get her to the infirmary soon.”

“I don’t think people say ‘infirmary’ anymore.”

“They don’t?”

“Never mind. Just tell me when Jo is safe, okay?”

“Absolutely. Let me go and check on them in person.” He got to his feet and started to run down the corridor away from me. “I’ll be right back,” he called over his shoulder.

Mattan never closed the door behind him, so I had a perfect view of their vestibule, now that it wasn’t blocked by Mattan’s massive frame. It looked like a long curving corridor with many doors on both sides. Each door had two flat panel display screens, one on either side of it–probably showing what was on the other side of the door. And the whole area was bathed in white light.

I moved closer to the opening to get a better peek, but the light hurt my skin like it was made up of millions of little sharp bits of glass. I quickly moved back to a safe distance.

The door to my location was made of black wood, and sort of matched the other doors in this house. Unlike the Japanese homes I’d seen in the movies and comics, this one had no paper walls or partitions. The URTs were all about privacy, I guessed—the wooden-doors kind of privacy as opposed to the paper-walls kind. I was good with that. Who would want to go to the bathroom with paper walls? Sound travels. I didn’t think paper walls kept smells from traveling either.

The next door down the hall looked like a plain office door. From what I could make out on the monitor next to it, it led to some kind of closet–I could see boxes and stacks of toilet paper and one of those yellow rolling bucket things that janitors use. Our school had a few of those buckets and one of those closets–a janitor’s closet. I wondered what building that closet belonged to. Would doors that were close together in this white corridor be close together on Earth, geographically speaking? If I had designed the doors, I would have made it work that way. But the URTs might do things differently. It was always a mistake to assume aliens were just like us. I’d read enough science fiction to know better.

I tried to make out the next door down. The white light created a glare, a bit like fog, which obscured things that were farther away. That door looked metallic, though, and wasn’t shaped like a rectangle. Did that mean it was on some kind of a ship? Maybe a submarine? If I were in charge, I would have made doors on planes and trains and boats. Sometimes, it’s good to have fast transportation even when you have cool extra-dimensional shortcuts.

I wondered if the URTs had a space station. If I could program one, I would have made a big one. Then I would create a door to this space station, and any time I wanted I would have just stepped through into Earth’s orbit and taken pictures of the continents rolling by. But that’s just me.

I felt a hand on my shoulder, and I jumped.

“Sorry, Peter,” my dad said. “How is it going? Have you heard anything yet?”

“They found Jo, I think.”

“Where?”

“Mattan said she was someplace in Siberia,” I said. “The URTs have a base there, apparently.”

“Of course they do,” Dad said. There was quite a bit of sarcasm in his voice. Dad must have noticed that I noticed, because he added, “My mom–your grandmother-and I lived in Siberia when the URTs first found us. It makes sense that they’d have a permanent door to that location.”

“Do you remember when they found you?” I asked. I’d never thought about my dad being little before. But obviously he must have been. And I sort of knew he was born in Siberia. “It was near Lake Baikal, right?”

“Peschanoye Selo–literally translating to ‘Sand Village.’ It was a small settlement back then. I think it’s a ghost town now. No one lives there any more. Is that where they found Jo?”

“I don’t know. Mattan did this cool thing with his fingers and sucked the information right out of the floor.” I pantomimed the motion Mattan did with his hand. “He said that she had left their shelter and gone out into the snow. And then he ran back there to help.”

“You didn’t try to go after him, did you?”

“I…”

“What did you do?” Dad asked. He wasn’t angry, just curious.

“I tried to move a bit closer to the door, but the white light hurt. Well, not really hurt, more like prickled my skin. Anyway, I scooted back.”

“I see.” My dad extended his arm slowly toward the opening into the vestibule. He was careful and didn’t push his hand through. I watched as surprise and then fear flickered across his face, and he pulled his arm back and rubbed it. “Stay out of it,” he said.

“That was my plan,” I said. “How’s Mom doing?”

“She has one of those headaches again. The last several weeks have been difficult. I took her to our assigned bedroom to get some rest. I promised to let her know as soon as I knew anything.” He turned to go, and then added, “Stay out of there, but tell me as soon as you know anything, okay?”

“Yes, Dad.”

“And Peter? Good observation.” He moved his fingers the same way that I had just shown him while mimicking Mattan.

“Thanks, Dad!”

Almost immediately after Dad left, Gibbor showed up. My guess was that he had been waiting for Dad to leave.

“So what’s up, kid?” he asked.

“Just waiting,” I said.

“Hmm. Well, I think I’ll go and have a look.” Gibbor stepped past me and walked through the door into the vestibule. He had no problem with the white light, of course. I watched him carefully, and his facial expression didn’t change at all.

Someday, I’d be able to do that too.

You can buy “Coding Peter” on Amazon (and other places) here.

If you like the story, please consider leaving a review and tell your friends!