Belkin, L. (2010). “Keeping Kids Safe From the Wrong Dangers” New York Times Online. Retrieved on October 6, 2010: http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/19/weekinreview/19belkin.html?_r=1 Summary: Belkin puts the spotlight on the somewhat irrational behaviors of parents when it comes to protecting their children. With the best of intentions, they worry about kidnapping, school snipers, terrorist, dangerous strangers and drugs, while the most likely things to cause children harm are car accidents, homicide (usually at the hands of someone they know), child abuse, suicide and drowning. So why are parents constantly overestimating rare dangers while underestimating common ones? The author makes the point that evolution may have something to do with it in that our brains are not designed to process abstract or long-term risk, but rather to react to an immediate dangers for instance represented by a sound and make a determination of whether not it presents a danger. In today’s fast-paced world where we are bombarded with all kinds of worst case scenarios and sensationalism, our sense of proportions gets distorted. So, we end up driving our kids to play-dates, when a walk on their own may have been better both health and safety wise. User Groups: So how can parents make more…

Tag Archive for problem solving

Anchoring Errors, Background Knowledge, Background Knowledge Errors, Causal Net Problems, Diagnostic Errors, Featured, Mental Model Traps, Metaphor Mistakes, Misapplication of Problem Solving Strategies, Pipsqueak Articles, Product Design Strategy, Scaffolding

What is a p-prim?

by Olga Werby •

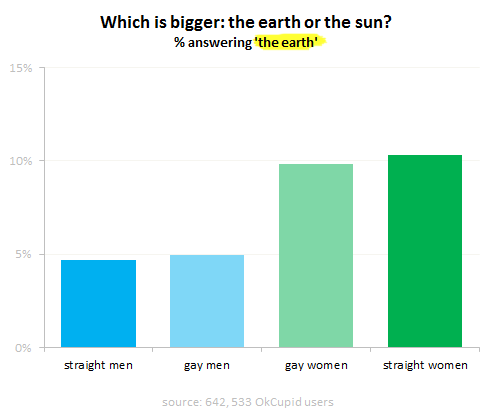

I’ve been using the p-prim ever since I’ve learned of them, back in my graduate school days at UC Berkeley. P-prims stand for phenomenological primitives and were “invented” by Andrea diSeesa, a UC Berkeley professor in the School of Education who also happens to be a physicist (diSessa, 1983). Visit his Wikipedia page and check out some of the cool projects he’s working at now. Before I give a definition of a p-prim, I think it would be good to give a few examples. Here’s a graph published by OkTrends on beliefs of various groups (in this case as defined by their sexual orientation) about the relative size of our sun versus the Earth (our planet). Even disregarding the differences in percentages due to sexual preference, an awesome 5 % to 10 % of our population believes that the planet we live on is larger than the star it orbits. Would this qualify as a p-prim? Yes: it’s not a formally learned concept; it describes a phenomenon; it’s a bit of knowledge based on personal observations: the sun looks like a small round disk in the sky; it’s a useful problem-solving tool when one has to draw a picture with…

Autopilot Errors, Background Knowledge Errors, Conceptual Design, Diagnostic Errors, Errors, Interaction Design, Interface Design, Interruptus Errors, Misapplication of Problem Solving Strategies, Mode Errors, Perceptual Blindness, Perceptual Focus Errors, Pipsqueak Articles, Product Design Strategy, Scaffolding, Users, Working Memory

The History of Usability

by Olga Werby •

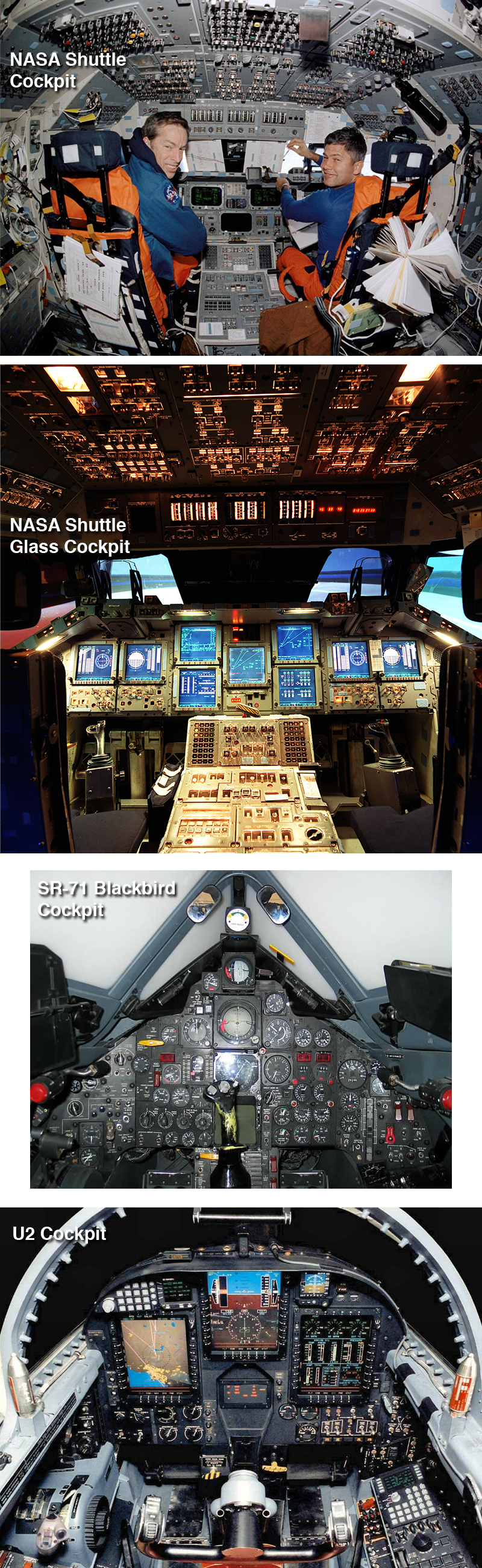

When did we start being concerned with usability? Some will say that such concern is part of being human: cavemen worked their stone tools to get them just right. Interaction design mattered even then. But the field of usability research really came into being when the tools we used started to run up against our cognitive and physical limitations. And to avoid hitting literal, as well as psychological, walls, it was the aviation engineers who started to think about usability seriously. While cars were becoming ever more sophisticated and trains ever faster, it was the airplanes that were the cause of most usability problems around WWI. Cars were big, but didn’t go very fast or had a lot of roads to travel on at the turn of the century. In the first decade of the 20th century, there were only 8,000 cars total in the U.S. traveling on 10 miles of paved roads. In 1900, there were only 96 deaths caused by the automobile accidents. Planes were more problematic. For one thing, the missing roads weren’t a problem. And a plane falling out of the sky in an urban area caused far more damage than a car ever could. Planes…

Background Knowledge, Background Knowledge Errors, Mental Model Traps, Misapplication of Problem Solving Strategies, Pipsqueak Articles

Grabbity and Other Folksy Wisdom

by Olga Werby •

We spend our lives engaged in problem solving: When should I leave the house to get to work on time? What can I make for dinner given the stuff in my refrigerator? How much work do I need to get done today in order to leave a bit earlier tomorrow? What’s the best driving route given the traffic report coming over the car radio? Can I make the this green light? Can I talk my way out of a traffic ticket? What’s the maximum amount I can pack into my trunk after a COSTCO run? How can I get that stain off the carpet? Is this blog good-enough to post? Looking over this sample list of problems, it’s easy to see that some have to do with temporal and spatial processing (e.g. packing the trunk, picking the best route, judging speed, making schedules), some with background knowledge manipulation (e.g. coming up with a recipe given a list of ingredients, looking up cleaning strategies), some with social processing (e.g. ability to analyze social situations and make correct predictions of possible outcomes—”I will get that ticket, if I run that red light.”), and some with metacognitive tasks (e.g. judging quality, comparing standards…

Attention Controls Errors, Conceptual Design, Contributor, Ethnographic & User Data, Interaction Design, Interface Design, Product Design Strategy, Scaffolding, Users, Working Memory

Depression’s Upside

by Theresa Bruketta •

Lehrer, J. (2010). “Depression’s Upside.” The New York Times. Retrieved on 29 June, 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/28/magazine/28depression-t.html Summary: Depression is a disorder that has long been associated with the anguished artist who is fixated on his work. The gloomy state of mind may have an upside and, according to research by psychiatrists Andy Thomson and Paul Andrews, it is this ability to be more attentive to our problems. Approaching the issue of depression from an evolutionary perspective, they believe it is not likely for the brain to adapt “pointless programming bugs”. Unlike other mental illnesses which occur in small percentages of the population, approximately 7 percent of people are afflicted with depression every year. Despite, the evolutionary problem which results from lowering one’s sexual libido (and limiting the urge for reproduction), depression could be viewed as an adaptive to the stressors of one’s environment. Neuroscientists in China observed a spike in functional connectivity in the brain allowing depressed people to be more analytical and able to stay focused on a difficult problem longer. The research of psychologist Joe Forgas, found that depressed people were better at judging accuracy of rumors, less likely to stereotype strangers, and had better recall memory. Rumination, the…

Background Knowledge, Background Knowledge Errors, Diagnostic Errors, Perception, Pipsqueak Articles, Users

Distilling Information

by Olga Werby •

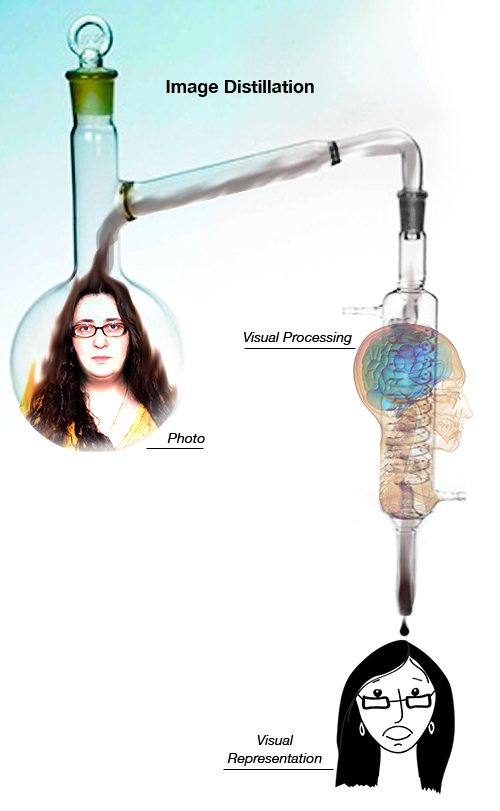

When it comes to my students’ participation in this blog, it’s all about distilling information found in the news to something product designers in our midst would find useful, on a practical level. Consider the illustration below. We see a person’s face (mine in this case). We can describe some of the features. But what do we actually remember? Remembering complex visual information is hard—too many details. Recalling a drawing is easier. That’s because an artist already distilled the complexity into its essential parts—only those details that are required to remind us of a particular individual are included in the rendering. We are all pretty good at judging wether a portrait looks like the person it was intended to represent. We can quickly say if it does or if it doesn’t. But it would be difficult to explain what details in the illustration make the likeness or what’s missing from the drawing that didn’t hit its mark. Distillation of information is hard. Some people are good at it, some are not. It’s an acquired skill. And each category (e.g. sensory like visual, audio, tactile or knowledge-based like physics, economics, biology) requires its own training and its own set of talents.…

Anchoring Errors, Background Knowledge, Background Knowledge Errors, Diagnostic Errors, Mental Model Traps, Pipsqueak Articles

Working Memory Limitations vs. the Size of Problem

by Olga Werby •

The illustration above comes from Wikipedia, which has a complete entry on the Asian proverb about blind monks who examine an elephant and generate multiple hypotheses of what it could be. In product design speak, these monks are doing collaborative problem solving with a shared goal of identifying a mysterious object—the elephant. The monks, the story goes, all come from different backgrounds: an old tailor touching an elephant’s ear describes it as cloth; an aging gardner hugging the leg imagines a tree trunk; an elephant’s tusk is envisioned as a weapon by an arms master. Each monk brings his own life’s worth of experience to bear on the problem, but each has very limited access to the whole. It’s easy to see how this story can be used to explain the pains of collaborative and cooperative group projects in which individuals focus on product design. Each person brings their own expertise to the table, hopefully contributing positively to the whole process. But this story is also a good metaphor for understanding problem solving in context of our very limited working memory capacity. Unlike elementary school math problems that we all calculated, real world problems are messy and don’t come with…