Our only truth is narrative truth, the stories we tell each other and ourselves—the stories we continually recategorize and refine.

— Oliver Sacks, The River of Consciousness , page 121

, page 121

Our memories are not static. Each time we reach for one, we refresh and form new neuron connections, in fact changing the memory itself via our contemplation of it. Like Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle — we can observe a particle’s momentum or its position but not both simultaneously — each time we recall a particular event, we change it due to that recollection. After the mental touch, the memory is no longer the same. And this is true not just in some metaphorical sense, but in a real, tangible, physical way — the act of recall alters the neuron structures forever! And yet we eagerly recollect our favorite memories, and we just as eagerly try to forget the painful ones (and the very act of thinking of those painful memories makes them that much stronger, that much more connected and integrated into our neural memory networks).

Social groups have always been aware of this property of memory. Cultures are molded out of stories, songs, epics, ballads, and now memes that bind us together by the endless repetition. “Titanic” is no longer just the name of a trans-Atlantic ship, it’s a synonym for a “disaster of epic proportions.” But such cultural references work only as long as the person grew up enmeshed in these stories. In fact, one of education’s main goals is to give students these cultural foundations, the shortcuts to understanding. And each culture has a unique set (subset), even if we now share a lot of global references.

One of the ways to create a sub-culture is to generate a “private” list of cultural touchpoints — a collection of stories that set apart the individuals in that group from all others. Memes have become particularly good at this. There are global memes, religious memes, cultural memes, professional memes, city-wide memes, school memes, and even family memes. But all of these are just shared stories, stored in our memories, and triggered through either passive recollection and active remembrance.

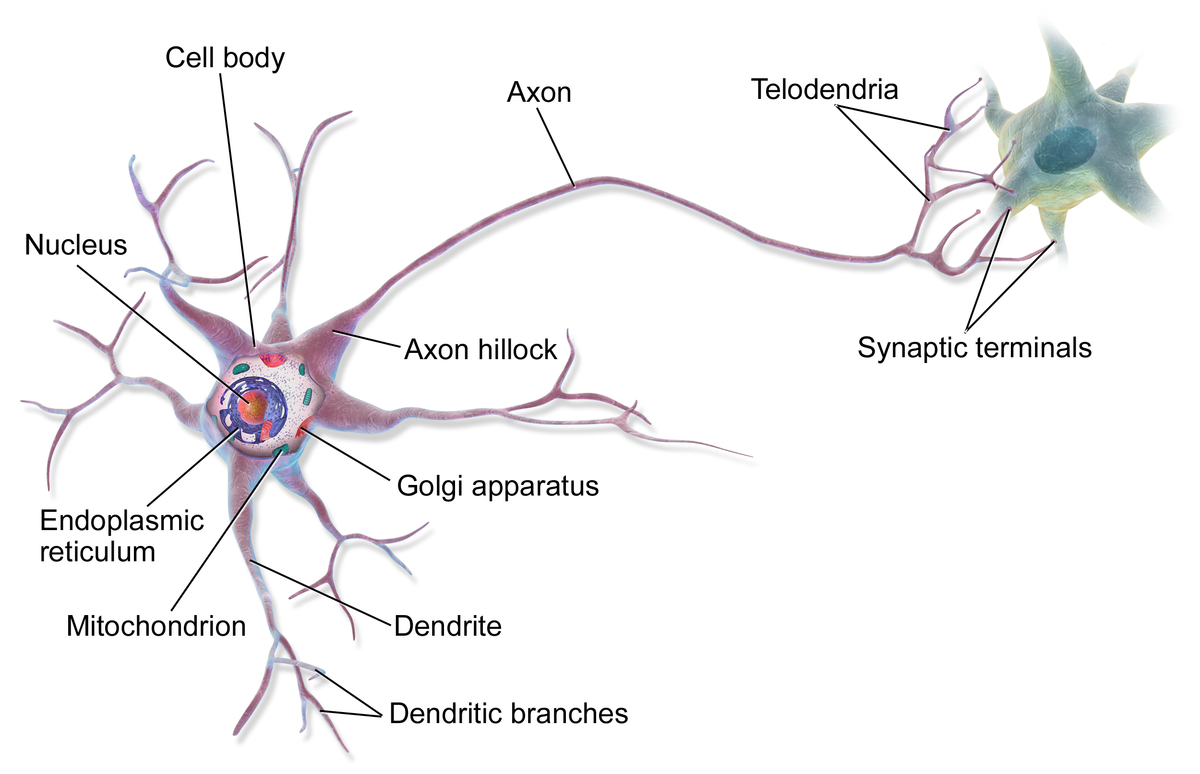

Passive recollection is achieved when a story is brought to mind via external circumstances — a word, an image, a video clip, etc. Active remembrance is when a person tries to remember, works at it. Most situations are a blend of the two mental activities. And each time the memory is “touched,” its connection to other memories, its strength of recall, its vividness, its availability is increased, not in just some abstract way, but in a very concrete, more axon connections kind of way.

So what if we want to make a particular memory stronger? What if we want to memorize something? Something important? Something we want to learn? Well, it seems like our ancestors have figured that part out — tell stories of the important stuff. Vivid, interesting, absorbing tales help us remember even the most difficult subjects. And in our society, increasingly more science focused (I hope), we need memorable stories about science. Fun experiments, field trips to museums, hands-on activities are good, but science fiction stories, when you add emotion to facts, are so much more effective. Teaching kids about medicine, or physics, or chemistry as part of a narrative creates a rich interconnected network of memories that are easier to recall.

But that means that we need stories that are true — science fiction with an emphasis on science! When we show kids stories with human and dinosaurs interacting, what they will remember forever is that humans and dinosaurs existed at the same time — not true, but oh so memorable. In fact, over 40% of Americans believe that humans and dinosaurs walked the earth at the same time.

There’s so much potential in storytelling as a means of transferring information. I wish we could embrace it fully. Ask kids to write their own stories or memes based on the science and history they’ve learned. Recommend books that help strengthen the learned facts with the emotional impact of a good yarn.

One last point — stories can be used for good or evil. Marketers and political operative have weaponized the stories’ potential to create strongly anchored memories. So it’s about time that the same technique is used for good.