This page will slowly accumulate the glossary of terms that I use in my work, classes I teach, and in the book. It will take awhile, but eventually, I hope to approach completeness.

-

A

- Action Cycle

- evaluate the state of the world –> interpret the data –> create a new goal –> create an intention to do an action that advances the state of the world closer to the desired goal –> figure out the actual physical motions that need to done to execute the intention –> evaluate the state of the world again

References

- Norman, D. (2002). “The Psychology of Everyday Things.” Basic Books. ISBN-13: 978-0465067107

- Affordances

- for the purposes of product design, affordances are user perceivable elements that suggest the possible range of possible actions with the interface that can be used to achieved a desired goal

References

- Norman, D. (2002). “The Psychology of Everyday Things.” Basic Books. ISBN-13: 978-0465067107

- Autopilot Errors

- inattention errors occur when we are very comfortable doing something—we are experts at performing the sequence of actions. For example, we rarely end up at a store when we are driving around looking for a particular address. So anytime a person is asked to perform the same action over and over again with only an occasional variation, there is a strong chance that autopilot errors will arise. Such errors are the bane of factory assembly line workers and can lead to serious injuries.

References

- Werby, O., Werby, C. (2010). “Cognitive Blindness—Looking for Sources of Human Errors with Product Interactions & Interfaces.” 2010 IADIS Conference: ITC, Humans & Society Conference, Freiburg, Germany

- http://www.pipsqueak.com/pages/papers.html

- Werby, O. (2008). Interfaces.com: Cognitive Tools for Product Designers. CreateSpace, USA

- Norman, D. A. (1988). The Psychology of Everyday Things. Basic Books. ISBN: 0465067093

B

- Behavioral Targeting

- a form of online marketing that uses behavioral tracking technology (using cookies—small text files that are exchanged between a web site and a person’s browser upon visiting the site) to display ads based on individual’s previous surfing history (if you visited a baseball site, then you will be targeted with baseball merchandize) on all subsequent web pages. As with Retargeting, the resulting effect can feel “creepy” when done poorly—a person might start to feel like he/she is being watched. Google is one of the companies that is actively pursuing this technology.

-

C

- Cognitive Blindness

- refers to the recognition of the difficulties designers face when they try to imagine cognitive differences between themselves and their users. The result is that product designers focus on designing products that are intuitive to them, but not necessarily so to their users. Users make mistakes, experience frustration, and develop negative attitudes towards products. For a simple example, consider the ability to remember a photographic image. Are you better then most at this task? How can we compare and judge the quality of visual memory? Did a person focus on details or the overall effect? Was the composition or color scheme more memorable? Did everyone see the same color?

References

- Werby, O., Werby, C. (2010). “Cognitive Blindness—Looking for Sources of Human Errors with Product Interactions & Interfaces.” 2010 IADIS Conference: ITC, Humans & Society Conference, Freiburg, Germany

- http://www.pipsqueak.com/pages/papers.html

- Darnell, M. J., (1996-2010). “Bad Design.” A Web site that contains a collection of poorly designed products and author’s experience with them together with a few design improvement suggestions: http://www.baddesigns.com

- Cognitive Surplus

- Clay Shirky introduces the concept of Cognitive Surplus at the 2010 TED Conference—the ability of people of the world to volunteer (have enough spear time after providing for life necessities) on large-scale problems and products and the availability of technology to link those individuals into cooperative work groups. Both conditions have to be satisfied to create Cognitive Surplus. Shirky goes on to give examples: the birth of Ushahidi and crisis mapping, Wikipedia, open source software.

References

- Shirky, C. (2010). “How cognitive surplus will change the world.” 2010 TED Conference

- /blog/product-design-resources

- Conceptual Design

- an initial stage of product design that focuses on what a product does. The start of the process is identifying the audience and then visualizing what that audience wishes from a particular product. Then we can identify the goals and expectations of each audience type under the different circumstances of use. We can then seek ways of satisfying those user goals and shaping those expectations. Rather than driving this process by what can be done technically, it’s best to adapt an “audience experience” approach to determining a product’s feature set. Conceptual design also takes into account the business needs behind product development: business goals, budget, man power, time-frame, resources, technical capabilities, etc. Conceptual Design answers the question: “What does this product do?”

References

- Werby, O. (2008). Interfaces.com: Cognitive Tools for Product Designers. CreateSpace, USA

- http://www.pipsqueak.com/pages/design_process.html

- Culture

- is defined as a those aspects of social patterns, knowledge, customs, and language that get passed on to members of a particular group. These groups could be quite small in size, as in office workers of a small branch of a paper-selling company in an upstate New York, or as large as citizens of United States of America. It all depends on how we want to slice up the population, how fine grain we want our distinctive variabilities to be. Members of one culture can usually easily identify each other by the turn of a phrase, by the clothing they choose to wear, by actions they take, by the food they like, and so on. Members from different cultural groups might have problems understanding each other even if they speak the same language.

-

D

E

- Evolutionary Design

- an incremental improvement to product design driven by selection of features that increase utility and comfort over many generations of use. For example, consider the design of a chair. Over eons, humans have carefully improved their implements for sitting. From logs and rocks, we moved to fine craftsmanship that doesn’t only consider our ergonomic needs in its contours but also our desire for beauty. In the past, furniture was expected to last for the lifetime of its owner and beyond. Wood was chosen for its durability, color, and aesthetically pleasing grain. The height of the back rest and legs were measured and adjusted to fit the users. The width and depth of the seat as well as the curvature of the surfaces were engineered to support generations of resting bodies. But these designs didn’t spring forth overnight. Each generation of chairs had functional improvements on past versions and incorporated the cultural definition of beauty of its day. Improvements were made slowly. People had time to live with and appreciate the fine design of a chair. And as flaws in design were discovered, the next generation of chairs incorporated furniture makers’ solutions to those problems. Such evolutionary design has the following structure: design—test—adjust—use—get feedback from users—adjust—use—get feedback—adjust—use—get feedback—adjust—use… For a chair, this design feedback loop spans thousands of years. Similar evolutionary design forces shaped many of our common tools: hammers, saws, files, pens, scissors, and so on.

References

- Werby, O. (2008). Interfaces.com: Cognitive Tools for Product Designers. CreateSpace, USA

F

- Flow

- an Optimal Experience. To be an Optimal Experience the activity has to consume total attention, be engrossing; has to be enjoyed by the person doing the activity; has to be performed under appropriate environmental conditions; and has to be cognitively exhilarating—not too hard and not too easy. Flow happens when all four conditions are satisfied. An optimal experience lives in an Intellectual Goldilocks Zone.

References

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1991). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper Perennial; ISBN: 0060920432

- Werby, O., (2009). “Designing Optimal Educational Experiences.” 2009 AACE Conference: ED-MEDIA, Honolulu, Hawaii

- http://www.pipsqueak.com/pages/papers.html

- Werby, O. (2008). Interfaces.com: Cognitive Tools for Product Designers. CreateSpace, USA

G

H

I

- Interaction Design

- a stage of product design that focuses on how a product behaves. It touches all the points of contact between a product and the user. As such, it unlocks the functionality of a product. Information architecture is part of interaction design. For example, during the interaction design period of a Web site, the designer might determine how the Web pages organize the content. Interaction Design answers the question: “How does the product do it?”

References

- Werby, O. (2008). Interfaces.com: Cognitive Tools for Product Designers. CreateSpace, USA

- http://www.pipsqueak.com/pages/design_process.html

- Interface Design

- a stage of product design that focuses on how the product looks and feels. Often the problems of look and feel are mistakenly thought to be the entire design problem. But look and feel is only successful if the other design issues have been carefully crafted first. Interface Design answers the question: “How does the product look and feel?”

References

- Werby, O. (2008). Interfaces.com: Cognitive Tools for Product Designers. CreateSpace, USA

- http://www.pipsqueak.com/pages/design_process.html

- Interruptus Error

- an interruptus error occurs when you forget what was being done in the middle of an action. You opened the refrigerator but then forget why you were there—it just slipped your mind. You were trying to make a point, but forgot what you were going to say—you lost your train of thought. In both cases, working memory got overloaded with other thoughts or outside resulting in an awkward moment. These are also examples of attention control errors—failure to keep the ideas in working memory by paying attention to them. People who daydream a lot or who get easily preoccupied or distracted suffer interruptus errors all the time. The same is true for anxious individuals—most of their attention is taken up by worrying, leaving only a small sliver of working memory space to deal with current reality. Interruptus errors can be particularly damaging for individuals who have a smaller than average working memory. These people already have a hard time managing the in and outflow of information. If, on top of this limitation, their attention easily wanders away from the task at hand, their performance suffers.

References

- Werby, O., Werby, C. (2010). “Cognitive Blindness—Looking for Sources of Human Errors with Product Interactions & Interfaces.” 2010 IADIS Conference: ITC, Humans & Society Conference, Freiburg, Germany

- http://www.pipsqueak.com/pages/papers.html

- Werby, O. (2008). Interfaces.com: Cognitive Tools for Product Designers. CreateSpace, USA

- Norman, D. A. (1988). The Psychology of Everyday Things. Basic Books. ISBN: 0465067093

J

K

L

M

- Mental Model

- a mental representation of how something works. People have thousands of mental models of devices they use everyday: computers, calculators, cars, cameras, camcorders, cats, coffee makers, c-sections, coolers, spray canisters, rice cookers… Mental models evolve based on observation. Unfortunately, people are not very good at making accurate observations. Individuals tend to pay attention to things they think are relevant and omit those that don’t seem to be connected to the object of interest. Thus it’s easily decide that two events form a pattern even when they have nothing in common other then spatial or temporal proximity. Understanding the mental models that the users are likely to bring to the products is key for designers. Interaction designers can help users form more accurate mental models by creating diagrams or making action-sequence links more visible. Optimally, designers want to maneuver the user into taking a single action—the only obvious and right thing to do with the product. Like mental models provide explanations and could be right or wrong and they might generate good predictions or bad. And mental models can be completely wrong and still have pretty good predictive powers. Users have lots of mental models, but so do product designers. And designers are not immune to generating wonderfully outlandish ones. But the mental models don’t end with product designers; they get released into the world through the products they create. Mental models don’t only affect how users interact with products. They also change how designers approach them.

References

- Werby, O., Werby, C. (2010). “Cognitive Blindness—Looking for Sources of Human Errors with Product Interactions & Interfaces.” 2010 IADIS Conference: ITC, Humans & Society Conference, Freiburg, Germany

- http://www.pipsqueak.com/pages/papers.html

- Norman, D. A. (1988). The Psychology of Everyday Things. Basic Books. ISBN: 0465067093

- Norman, D. A. (1983). “Some Observations on Mental Models.” In Gentner, D. & Stevens, A. (Eds.), Mental Models. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. (pp. 7-14).

- Young, R. M. (1983). “Surrogates and Mappings: Two Kinds of Conceptual Models for Interactive Devices.” In Gentner, D. & Stevens, A. (Eds.), Metal Models. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. (pp. 35-52).

- Mode Errors

- result when a device has multiple modes of operation, making an appropriate action in one mode give an erroneous result in another. This is the familiar remote control error—you press the play button for the DVD while the remote is in a TV mode and nothing works as expected. This is just another form of attention control error. Unfortunately, as devices get smaller and smaller, designers rely on one button to do multiple actions, thus spawning numerous mode errors. And while they seem harmless (you can always just try switching modes), some people never get comfortable with the operation of some devices due to multiple functionality of controls. And in cases like car radio buttons, which tend to do double duty as CD controls, drivers can get into accidents while they fiddle with mode controls.

References

- Werby, O., Werby, C. (2010). “Cognitive Blindness—Looking for Sources of Human Errors with Product Interactions & Interfaces.” 2010 IADIS Conference: ITC, Humans & Society Conference, Freiburg, Germany

- http://www.pipsqueak.com/pages/papers.html

- Norman, D. A. (1988). The Psychology of Everyday Things. Basic Books. ISBN: 0465067093

- Carroll, J., Thomas, J. C. (1982). “Metaphor and the Cognitive Representation of Computing Systems.” IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, & Cybernetics. 12(2), 107-116.

N

O

P

- Perceptual Blindness

- an attention control error—it occurs when individuals focus so intently on a task that the miss obvious information coming in through their senses. Selective attentional focus in combination with limited working memory resources can be the source of many user errors.

References

- Simons, D. J., Charbris, C. F. http://viscog.beckman.uiuc.edu/djs_lab/

Q

-

R

- Retargeting

- a form of online marketing that uses tracking technology (cookies—small text files that are exchanged between a web site and a person’s browser upon visiting the site) to display ads for a particular item that a person seemed interested in (when that person visited an e-commerce site) on all subsequent web pages. The resulting effect can feel like “synchronicity” when done well and out right “creepy” when done poorly—a person might start to feel like he/she is being watched. A company Criteo sells the technology for Ad Retargeting.

References

S

- Skeuomorphic Design

- is an interaction and interface design approach that focuses on reproducing the look and feel of real world products.

-

T

-

U

- User-centered Design

- a design philosophy that puts the users’ needs at the center of the design process. It states that design is iterative in nature and users should be considered at multiple stages of product development. Designers are encouraged to try to think like users when coming up with design solutions. These solutions are then exposed to real users. Testing reveals some of the design flaws. Designers then are supposed to correct them and iteratively go through this process again and again.

References

- Werby, O. (2008). Interfaces.com: Cognitive Tools for Product Designers. CreateSpace, USA

V

-

W

- Working Memory

- where all the thinking takes place. It’s where we manipulate ideas that we pull from long term memory, store interim solutions, and examine observations coming in from our senses. But working memory is very limited. The common proverb, “he’s able to walk and chew gum at the same time,” is the commentary on the limitations of working memory. It’s very difficult to do multiple tasks simultaneously—working memory gets easily overloaded and we lose track of important information (e.g.: the next sequence in a complex routine, the first digits of the telephone number, car keys).

References

- Werby, O., Werby, C. (2010). “Cognitive Blindness—Looking for Sources of Human Errors with Product Interactions & Interfaces.” 2010 IADIS Conference: ITC, Humans & Society Conference, Freiburg, Germany

- http://www.pipsqueak.com/pages/papers.html

- Werby, O. (2008). Interfaces.com: Cognitive Tools for Product Designers. CreateSpace, USA

- Woolfolk, A. E. (1998). Educational Psychology, Seventh Edition. Allyn & Bacon, Needham Heights, MA

X

-

Y

-

Z

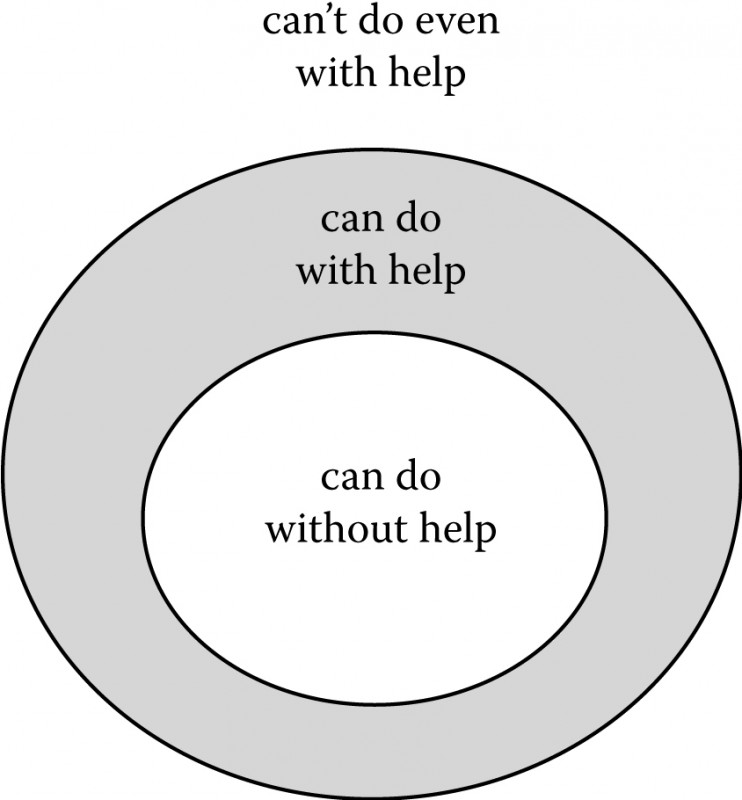

- Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD)

- a concept introduced by a Russian psychologist, L. S. Vygotsky, in his theories on human knowledge acquisition shortly after the Russian Revolution. ZPD is the zone between what students know how to do on their own and what they can’t accomplish even with the help of a great teacher. Stated another way, it’s what a student can achieve with guided assistance. All effective teaching efforts should be aimed at this zone. Efforts aimed beyond this zone, according to Vygotsky, will be ineffectual.

References

- Vygotsky, L. S., (1978). Mind in Society, The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Werby, O., (2009). “Designing Optimal Educational Experiences.” 2009 AACE Conference: ED-MEDIA, Honolulu, Hawaii

- http://www.pipsqueak.com/pages/papers.html

- Werby, O. (2008). Interfaces.com: Cognitive Tools for Product Designers. CreateSpace, USA

2 comments for “Glossary”