The “Why” questions are important part of design: Why are we building this product? Why would users want it? Why us? Why now? Why this technology?

The value of any question asked during the design process is in how the answer to that question helps advance the project; or help the design group bond; or reveal a significant insight into the problem that the group is trying to solve; or help clarify the use scenario; etc. All such questions are about moving the project forward. But it is easy to get sidetracked here, and I saw just that at the NIH biomedical research design brainstorming meeting.

Before I proceed, let me describe a bit of background research and give a concrete example when the wrong answer to the Why question jeopardizes the design solution.

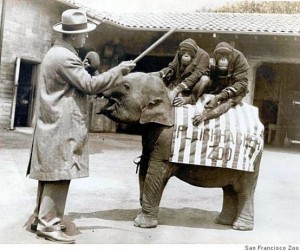

About ten years ago now, we were asked to design a set education materials for the San Francisco Zoo. The problem was lack of structure for school visits. San Francisco public schools allow all elementary school children to visit the city zoo once a year. That’s a lot of school children…and a lot of visits per kid. But do these students learn anything during these visits? And do they manage to learn something different each year? The answer seemed to be no.

Part of the problem was the changing mission of the zoos in general — from a strictly entertaining ventures that they were at the turn of the last century, zoos evolved their missions to focus on conservation. Somehow, having all those animals behind bars for visitor enjoyment seemed more palatable if wrapped in a coating of saving the species. The Why question for the zoos’ existence have radically changed (at least in the Western World). So how can this message of conservation be driven home to school children?

The issue with the “Why do these animals need saving?” question is that the answer leaves many helpless to affect change. There’s been research done on this (here’s one example) — we now know that when visitors to zoos are told of habitat destruction, of species extinction, and of animal suffering but given only the option of donating a few dollars, they turn off. It’s very discouraging to feel bad and helpless when faced with what is presented as an intractable problem. “But what can I do? Not much…”

When faced with a problem, we want to be able to find a solution and act on it. People — all people — hate feeling helpless (or too out of control). We get fatigued when continuously assaulted by negativity.

Why questions tend to focus on emotion. And emotion is a strong motivator — it helps focus the goals; it spurs interest and focuses attention; it helps bind individuals into action groups; and it prepares the body for physical response.

Why questions can focus on positive or negative emotions. If the focus is on negative emotion, designers have to develop cognitive scaffolding to direct that negative emotion into positive actions which ultimately make individuals feel good about themselves.

So in the case of zoos, we created materials (educational training and scripts as well as messaging) that gave visitors options of what they could do to drive change. Students at each age level were given “conservation tools” that the could use: recycling strategies, energy conservation ideas, food choices that protect the environment, etc. In short, things/actions that would empower them to change the world, even if on a very small scale.

Why We Should Promote Citizen Science

Getting back to the NIH citizen science discussions, there was a point in discussion when the Why question was asked. But the answer left (most if not all) people uncomfortable and unable to challenge it without generating negative emotions (guilt). The answer given to “Why are we doing this?” was a picture of a girl who died of cancer — “we are doing this to stop this from ever happening again.” On some level that’s true, but it is not a productive answer. Little girls will continue to die from cancer and other horrible diseases for many many years to come. We all know this. What’s more, when little girls born in the West stop dying from cancer, girls born else where will continue to do so for a long time afterward. Medical miracles are not evenly distributed…

But there are productive answers to the Why question of citizen science led biomedical research and the free sharing of personal genotype, phenotype, and other medical information. And here are just a few:

- Make a Difference Argument: We want for everyone to feel that they can make a positive difference in someone’s life.

- Have Fun Argument: We want for everyone to know that science is a lot of fun.

- Permission Giving Argument: We want to empower individuals to do science, to participate in research, and to engage with biomedical community.

- Be a Part of the Community Argument: We want people to feel like they are members of a community working to do good in the world.

- We are All in It Together Argument: We want to remove the “us versus them” paradigm in medicine, in research, and in science. We are all productive and contributing members of the biomedical community.

- Break the Barriers Argument: We want to remove fear barriers to participation.

- Give Back Argument: We want to give individuals an opportunity to contribute.

- Education Argument: We want to encourage scientific literacy.

- Empowerment Argument: We want to give individuals power to do something even in personally medically difficult circumstances.

- Membership Argument: We want to make sure that people don’t feel isolated or alone.

None of these arguments are based on emotion of guilt. Citizen science is important not because people die, but because this is the root of science. Before science became a profession, every person could contribute. The “us versus them” distinction between scientists and regular people is very new. Scientists are regular people and regular people can do science. With all of the new technology that helps collect data and provides easy access to training, the barriers to entry are mostly psychological. NIH can help empower individual to do science.

So as the French say: Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité — freedom to participate in citizen science; equality of all contributors (professional and amateur scientists alike); and membership in a scientific community.