Stress is an actor in all our lives. As we grow up, our stress grows too. We perceive that stress as a sign that we are coping with more than our historical share. Every generation believes that their stress surpasses that of the generation before. So it is probably just an illusion — or delusion. What’s most important is how we cope with stress.

Not all stress coping mechanisms are learned. Some are probably encoded — they come for free with our genetics. It can be easier to see these mechanisms in action by observing animals — particularly pets, whose behaviors we know intimately. Take, for example, two very different species that we have had as pets over the years — Terri the tortoise and Kushy the ferret. Terri comes from an ancient lineage of chelonians (Greek word for tortoise), who have walked and swam upon the Earth for hundreds of millions of years. Kushy the ferret is of the Mustelidae family — weasels and skunks. Kushy was a descendant of a domesticated breed of ferrets that first became pets about four thousand years ago. We bought Kushy at a pet store; Terri was a rescue. Terri’s natural habitat is a rocky desert in Kenya, but she is a city sophisticate and prefers a shoe closet. Kushy liked to hang out inside a curtain hem, eating Cheerios.

So what stress coping strategies do a tortoise and a ferret employ to manage their stressful lives as pets in a loving household? When Kushy got scared, he puffed up. He arched his back. His fur stood on end, making him look bigger than he was. He hopped to accentuate his size even more. As he made himself ferocious, Kushy slowly backed away from the threat. Then, just a few feet from where he started his stress behaviors, he rolled over and fell asleep. Kushy’s anxiety reduction was to act tough for a few seconds, sleep, and hope the world would return to its sunny self after a bit of time. Kushy is a mammal — perhaps not a very close relative to humans, but much closer to us than any reptile.

Note: Kushy’s epoch was before digital photos, thus I don’t have many images of him. He was much cuter than this.

Terri has a very different approach to anxiety. She ramps it up. We recently transported Terri in a car. She doesn’t like vibrations of any kind, so we knew it would be a rough ride and it was. Terri used all her strength to push against the top of the transport box. She was relentless, digging and pushing, and pushing and digging, trying to get out for the entire journey. She didn’t respond to my voice as she usually does. She didn’t respond to stroking. She wanted nothing to do with the box but to get out of it. She was persistent. She was relentless. She wasn’t discouraged by failure, she just pushed harder. Terri has always insisted on her own way of doing things. She wants what she wants and is willing to fight to the end to get it. That’s a reptile for you! She doesn’t always succeed, but she tries very hard. In the photo below, Terri is trying to escape a little garden enclosure — she hates being outside and prefers floors and carpets to grass. She didn’t fit under the metal grate but she never stopped trying. Feel free to follow Terri on Instagram: #CucumberPrincess.

Terri and Kushy have very different responses to stressful situations. Both strategies are probably valid. (Not sure about falling asleep without hiding first, but then Kushy was never really in danger, was he?) And these responses define how species do over time — do they persist over hundreds of millions of trips around the sun or do they arise and disappear in the geological blink of an eye?

Humans, of course, not only have innate evolutionary strategies to fall back upon during life’s stresses, we also have access to self-help books, TV shows, and even therapy. We have parents and grandparents who can share their wisdom and experiences, and we can fall back on friends for comfort. We are social animals and seek comfort from others of our kind.

Thus we are particularly tuned to stories about how heroes manage to overcome stressful situations. We enjoy these kinds of stories, be they about love, space, fantasy, or politics. And, as authors, we continually put our characters into stressful situations and come up with creative ways of getting them out of trouble — or not. I do my share of smiting my characters with suffering and abuse. But I also enjoy mostly happy endings — the suffering should pay off.

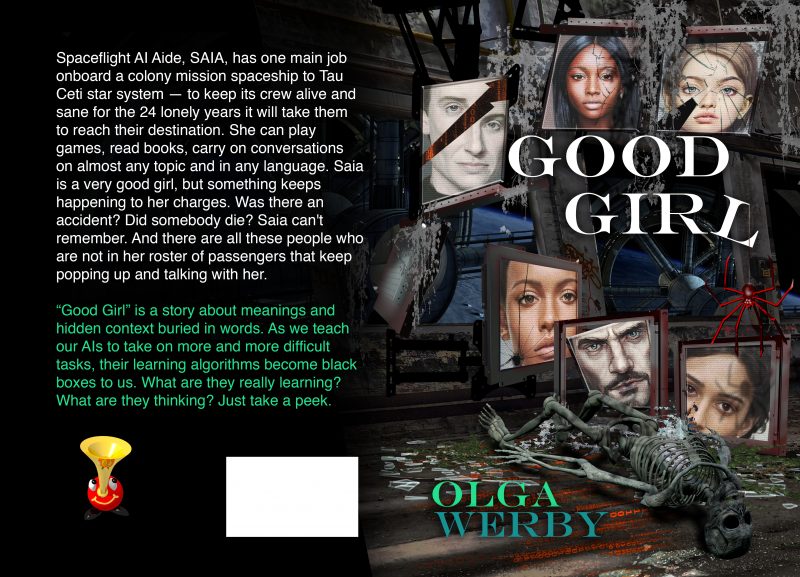

This time around, I’m making one of my Job characters, in the guise of a strange, sentient AI, part of a collection of indie mystery fiction. Hope you will give Good Girl a go or try some of the other books in this collection.

I will also make Good Girl free on Amazon for five days, starting August 15th.