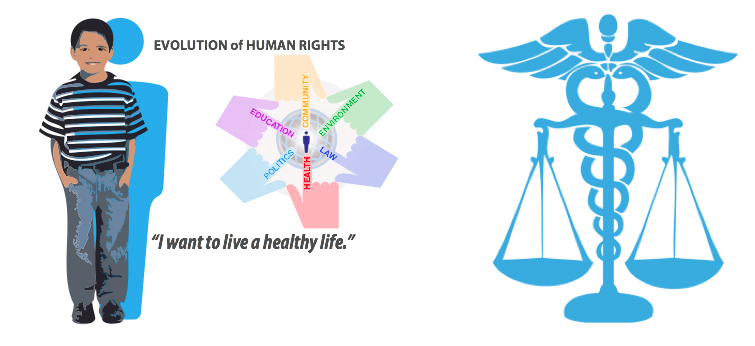

“I want to live a healthy life!”

For as long as humans have lived in groups, this meant a social covenant — conforming to rules set by many to insure mutual survival.

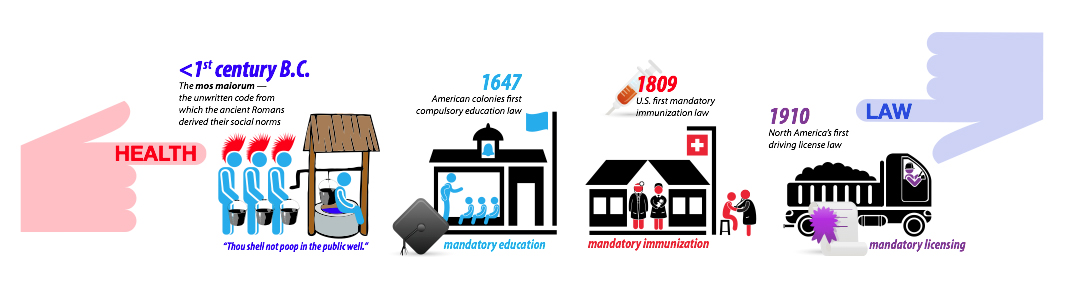

One way or another, health and law have been intertwined for millennia:

- don’t poo in a public well — one of the first health edicts along with burial customs

- religious food-limiting laws — limiting food born illnesses from decimating communities

- mandatory immunization — the need for herd immunity

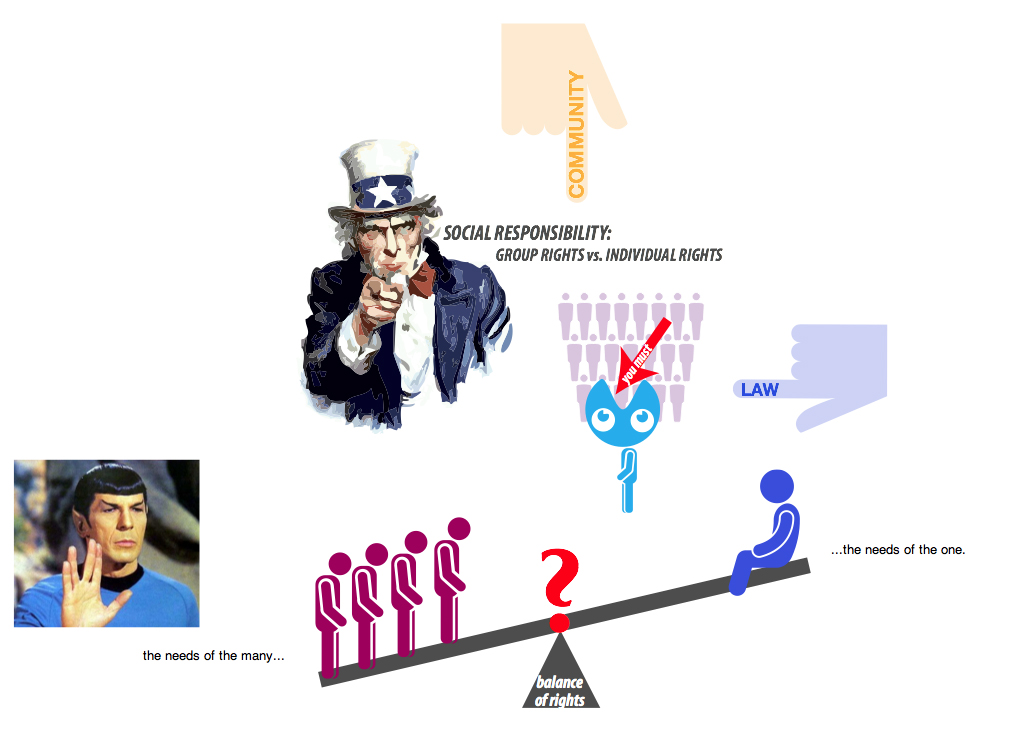

Health and community are mutually entangled. The price of living in a community means giving up certain personal rights:

“the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few or the one”

But this is a delicate balance. As a group, societies have done horrendous thing to individuals in a name of greater good:

- taking a right to privacy

- forced quarantines, treatment, and sterilization

- compulsory rehabilitation

- subjugation of women and minorities

Starting about the mid of the last century, the awareness for the need to protect the rights of the few and the one from the many grew in its momentum.

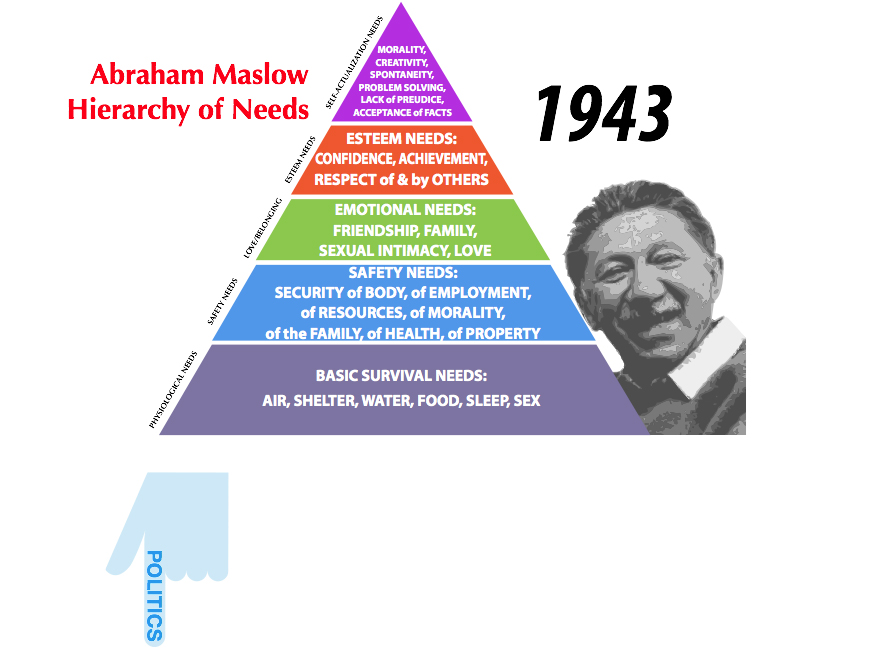

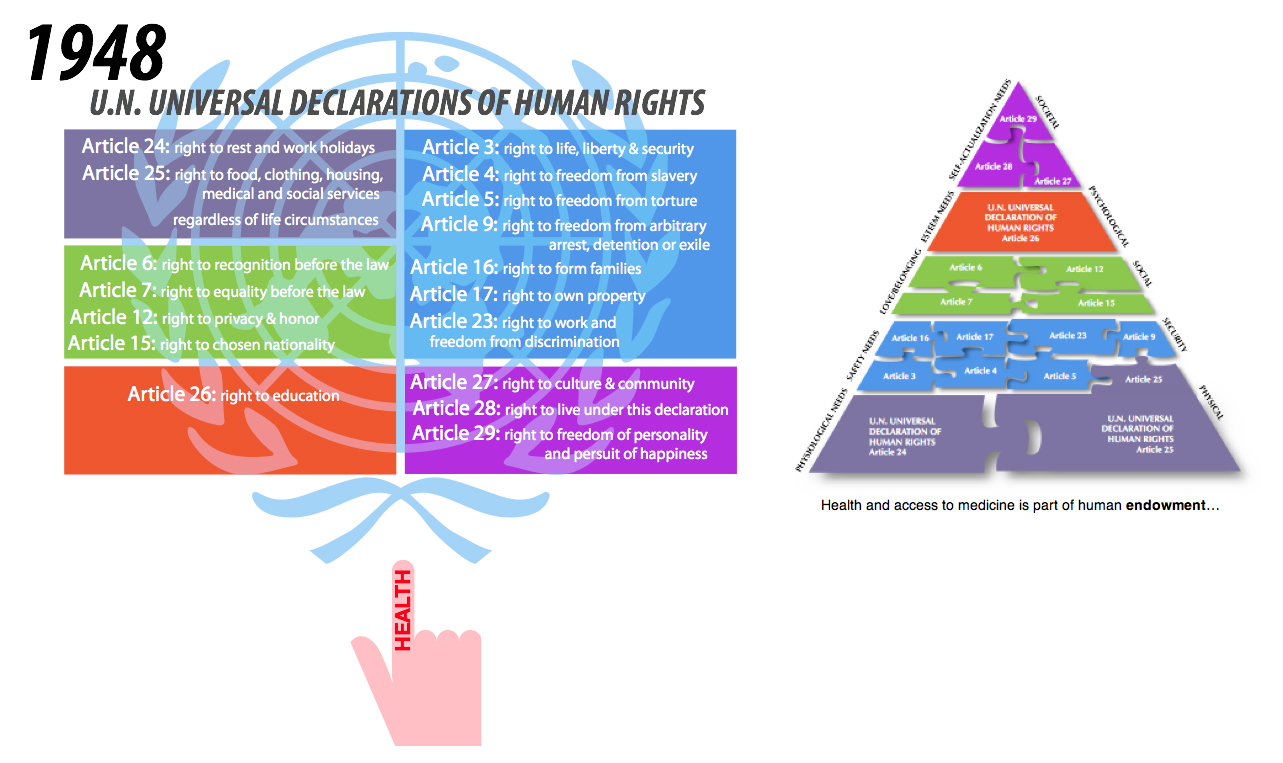

It was striking to me how the 1943 Abraham Maslow’s Pyramid of Human Needs became an echo for 1948 UN’s Declaration of Human Rights.

In particular, it’s easy to see how the careful construction of Maslow’s Physical Needs, Security Needs, Social Needs, Psychological Needs, and Societal Needs reflect the 29 UN Articles of Human Rights.

And in one form or another all those needs and rights revolve around health.

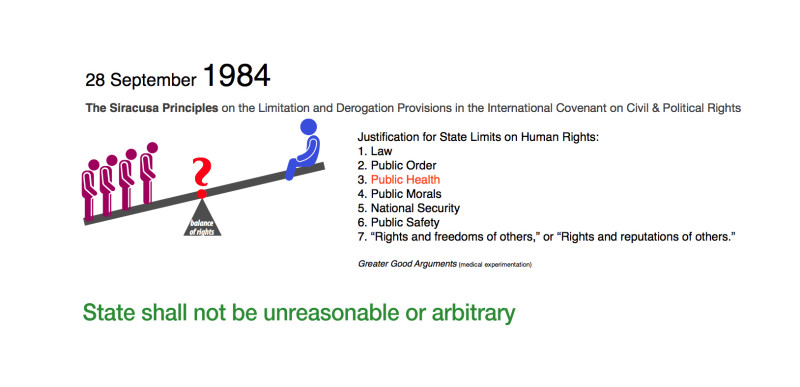

It was not until almost 40 years later, in 1984, that The Siracusa Principles created an international covenant on Civil and Political Rights of Individuals.

It was a set of principles that limited state’s powers and tried to safeguard individual freedoms and rights. The State could take away human rights for the Greater Good in cases where it needed to

- maintain order,

- or during epidemics,

- or when it interfered with majority morals (think nudity),

- or in case of state security (Martial Law),

- or when public safety was a primary concern (think train derailment),

- or when the actions of one individual interfered with those of others.

But Greater Good arguments can lead to some very unpleasant outcomes — think medical experimentation.

The Siracusa Principles stated that the State couldn’t be arbitrary or unreasonable when it took away human rights — in a quarantine, for example, infected people had to be treated equally. A politician’s kid had to be treated the same as my child.

All members of the group are to be treated equally.

But let’s get back to health and human rights. We know what leads to poor health outcomes:

- social & economic status

- gender discrimination

- racial discrimination

- religious discrimination

- moral/cultural discrimination

- ability discrimination (physical and cognitive)

- environmental and geographic location

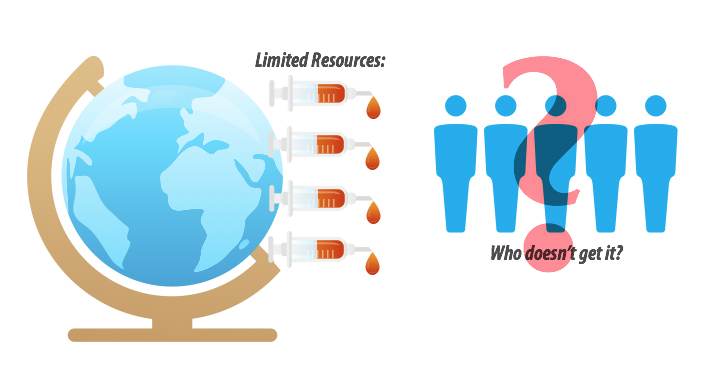

One of the reasons for discrimination is limited resources — we don’t have enough for every human on this planet. So who doesn’t get it?

When we develop a Declaration of Human Rights, meaning all human, how do we think about limited resources versus opportunities to lead a healthy life?

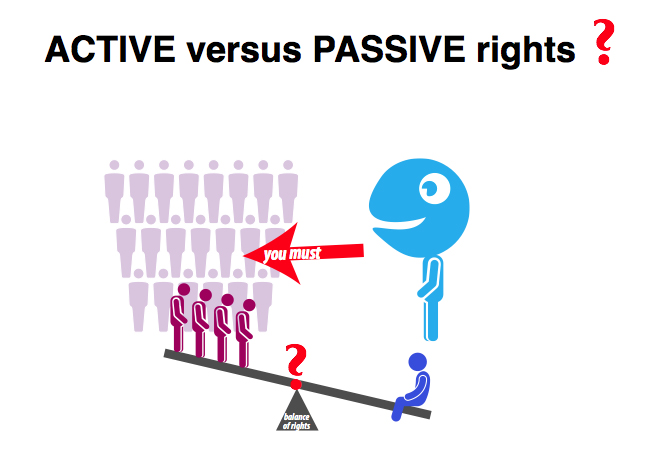

So consider Passive versus Active Rights.

This is a difference between YOU MUST and YOU SHOULD TRY.

As a society, we are great at forcing individuals to conform — YOU MUST NOT

But we are not very good on the other direction — THE STATE MUST…

If all humans on Earth have a right to be healthy, then it is the responsibility of all of us to make it so — this is the ACTIVE right. All give to a one or a few.

But in a PASSIVE rights, the edict is to try. Then depending on where you are born, you will have a better chance at being healthy.

“The right to health does not mean the right to be healthy… But it does require … policies and action plans which will lead to available and accessible health care for all…this is the challenge facing both the human rights community and public health professionals.” — Mary Robinson, former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights

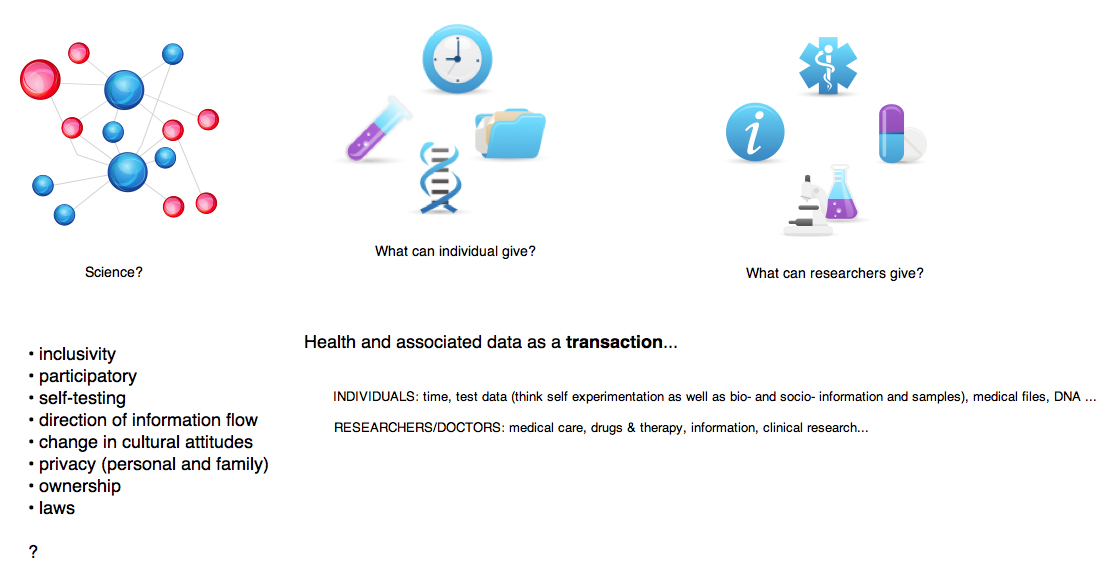

As far as research and science, health is a transaction — individuals can contribute data, time, and resources. Professional Health Community contributes medical care, drugs & therapy, information, clinical research…

But transactions only work well when all parties understand what they are contributing to the bargain. When contributions are not arbitrary or capricious. When all involved are able to make informed decisions when entering into this covenant.

Right now, individuals seem to be on the Passive rights side of the bargain…

I just returned from the Health Foo Conference. For two days we talked, debated, shared ideas, demoed products, and bonded over the future direction of health — How do we share data? What about citizen scientists? How do we develop new drugs? Where’s the money? Gamification of health? Health and behavioral economics? Nudging for better health? Who owns data? Big data? Data silos… Lot’s of ideas, lot’s to think about.

It felt like we were the futurists of health. And as such, we have to think about health globally — we can’t shy away from discussions of human rights in a context of health.

One Last Thought

I go to quite a few conferences. Of all my prior experiences, the Foo Camp was probably one of the best. I always meet interesting people and sometimes leave with a few actionable projects. But this was different. The Foo Camp was a shortcut to trust — there was enough time spent and few enough people to achieve bonding. I trust people I met there and I gained even more trust of those individuals that I met previously. Higher level of trust means greater possibilities. Here’s to designing for good!