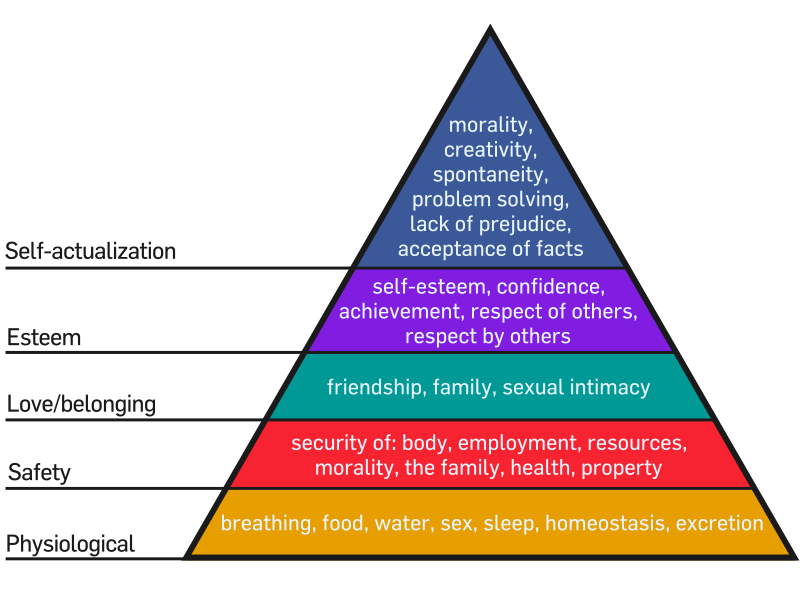

In 1943, Abraham Maslow published a paper on human motivation: “A Theory of Human Motivation.” The ideas (and diagram) from that paper have been widely used in business schools and management training programs. But these same ideas can be applied to human rights.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, signed into life by UN General Assembly on 10 December 1948, just five years after the Maslow’s publication of “A Theory of Human Motivation”, echoes the work via a set of Articles stating the rights of every human being.

Physiological Needs

Article 25 of The Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that everyone is entitled to the right of adequate food (and presumably water is included), housing and clothing (for homeostasis control), and medical care. The right to medical care implies to me the right to live healthy, or at least healthy to the best of ability of a particular individual.

This right to medical care as a universal right of all human beings can be interpreted to mean many things. For the purposes of the comparison to the Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, it could be interpreted as every human has the right to have their physiological needs met.

This could be very difficult — breathing can mean clean air and thus imply environment law limiting man-made pollutants. But how do we define clean? For individuals with asthma, air quality controls might need to be set quite high…

Maslow includes “excretion” as one of the physiological need, which could be interpreted as part of a set of employment rules — providing enough breaks for all workers to meet their sleep, nutrition, body function, even sexual needs. In fact, Article 24 of The Universal Declaration of Human Rights specifically addresses the rights of reasonable limitation of working hours and payed holidays.

Safety

Maslow’s Pyramid includes security of body, employment, resources, morality, the family, health (again), and property as forming the basis of the second foundation of human needs.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 3, states that “everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person.” While Article 4 specifically address slavery: “No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms.”

While not directly mentioned in Maslow’s Pyramid, torture and cruel and inhuman treatment from others are clearly in violation of both Physiological and Safety Needs. Article 5 specifically deals with this: “No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.” While Article 9 addresses arbitrary detention and exile.

Article 17, states that everyone has the right to own property which can’t be arbitrarily taken away.

Article 16 protects human rights in relation to having family and provides for equal protection as to marriage, entered with full consent of both parties involved.

Article 23 deals with the rights to work and having free choice of employment, as well as equal pay for equal work and right to form unions. Obviously, there are geographical considerations — different economies value similar work of a different pay scale (thus we are able to import goods from countries that have cheap labor…). The “choice” of employment is also culturally and geographically determined. But Maslow’s Pyramid only provides that a person needs employment…

Article 25 also provides for state assistance in event of “unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.”

Love/belonging

Friendship, family, and sexual intimacy form the third foundation of Maslow’s Pyramid of Hierarchy of Human Needs.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights provides for friendship, family, and sexual intimacy via instituting equal rights under the law, Articles 6 and 7; via protection from “arbitrary interference”, Article 12; and via right to a nationality, Article 15.

Friendships and families need equal protection under the law clauses to form and blossom, for friendship can only form among equals. Protections from “arbitrary interference” also provide for freedom to choose personal associations. And the right to nationality provides for group belonging.

Esteem

Abraham Maslow defines Esteem as self-esteem, confidence, achievement, respect of others, and respect by others. While many of the Articles of The Universal Declaration of Human Rights discussed so far are necessary for Esteem, a few address this need by providing for educational opportunities. Article 26 covers the human right to education.

I believe self-esteem, confidence, achievement, and respect of and by others is a direct outcome attaining full educational potential. This is clearly a very difficult goal to achieve.

Self-actualization

The top of the Maslow’s Pyramid is composed of self-actualization defined by morality, creativity, spontaneity, problem solving, lack of prejudice, and acceptance of facts. Access to education clearly plays a huge role in self-actualization. But The Universal Declaration of Human Rights goes even farther.

Article 27 provides for the right “to freely participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits”; as well as the right to “the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he is the author.” This is an amazing clause of The Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Article 28 stipulates a world where all of the rights outlined in The Universal Declaration of Human Rights are possible: “everyone is entitled to a social and international order in which the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration can be fully realized.”

And finally Article 29 outlines the duties of individuals to their communities.

Human Needs versus Human Rights

Abraham Maslow created a hierarchical set of human needs — self-actualization and esteem require that a person’s physiological needs and safety be met first. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is a collection of human rights. These rights not only spell out that the basic needs of individuals have to be met, but also go farther to guarantee some of the higher needs, like desire for love, family, and personal achievement.

Are the rights outlined by The Universal Declaration of Human Rights passive or active rights? Dr. Jacques Steyn gave a very good explanation of the difference during his 2011 talk on ICT & Human Rights: passive rights are aspirational — this is what we all hope to achieve someday; active rights are prescriptive — violations needs to be address by the world’s community.

By looking at Maslow’s hierarchical pyramid of needs, it’s clear that some needs/rights have to be active — right to food and water, to medical care, to shelter, freedom from torture… But other rights in The Universal Declaration of Human Rights seem to be more passive — right to education and self-furfilment. We hope that everyone has all of the rights, but we as a world community have to take some responsibility for insuring that the basic needs, the active rights, are met for all.

Health and the surrounding needs (access to medicine and food & water and safe environment) is clearly one of the active rights.

1 comment for “Health, Human Rights, and Maslow’s hierarchy of needs”