One: Dead Awakening

On the day his mother died, Pigeon learned he could fly.

It was a particularly cold night and Pigeon and his mother were curled up under a wad of blankets. His mom had collected them and piled them on top of a bunch of cardboard boxes to keep out the light drizzle that had started earlier in the day. She’d said she was very tired and didn’t want to go to the back of the restaurant to gather leftovers as they usually did; she just wanted to get comfortable. Pigeon didn’t mind too much. He ate the pastries they’d picked up a few nights before — sugar tastes great even stale. And the extra time meant that Pigeon could read his book for a few hours longer — always a treat. Living on the streets didn’t provide much time for leisure activities like reading.

Aside from settling in for the night early — about the time most people started their commute home — nothing was different that day. Most evenings, Pigeon’s mom would make them walk until they were sure the cops would leave them alone for the night. Pigeon didn’t like those “evening strolls,” as his mom called them. He always preferred setting up their nest of blankets and cardboard early enough to snag the best doorways. The competition was stiff, and since they were newbies in San Francisco, they were often pushed out and had to move. But if they grabbed the spot early enough, somehow they were more likely to keep it. That was the unwritten street code.

Even so, a few times they’d lost everything when some drunk just climbed in with them. Pigeon had yelled and screamed the way his mom had taught him. Once a passerby helped them get rid of the guy. But most people just pretended that he and his mom weren’t there at all. Their invisibility among the normals kept them safe and together, his mom always said. But now she was dead, and Pigeon was hovering about ten feet above their nest, watching the policemen as they tried to shake his mom awake and then slowly realized she was dead.

It frightened him, and he almost screamed, but Mom taught him never to vocalize unless he knew exactly the effect he wanted to have on the people around them. He wasn’t a baby, after all. Pigeon was eleven and seven months. They celebrated all of his full and half birthdays.

“She must have died in the early hours of the morning,” the policeman said to his partner.

Pigeon remembered snuggling up next to her last night, after he’d finished reading. She hadn’t minded, and she was so warm. She sure wasn’t dead then.

This morning, Pigeon had awakened as he always did, at first light. His stomach felt queasy. The rain had stopped, and he had reached for his mom to tell her he was going to get up, but his hand hit a cold metal pipe. That startled Pigeon awake. But it was what he saw when he opened his eyes that was truly startling. Although his back was still against the brick wall of the building, the blankets and cardboard were now more than a story below him — as were the police officers and his mother’s body.

“Must have overdosed,” the officer told his partner. “Hate this cleaning duty…” He pushed the boxes aside and started rummaging through the nest Pigeon and his mom had made the evening before. “It’s all just a bunch of crap.”

Pigeon dared not move — not that he knew how to anyway. There was a funny feeling in his gut, like when he would go a day without food, but different. Perhaps the pastries were bad after all? Pigeon was scared that the policemen would look up. And he didn’t like the way those men were poking his mom. She never did drugs — what did they know? He almost told them to put the blankets back on. Mom had said she was cold.

“OD?” The other police officer leaned in. “I’ll call for an ambulance.”

They’re going to take her away! Pigeon freaked noiselessly. His mom couldn’t be dead — she had been fine just a few hours ago. They had both been fine. And now they weren’t. Pigeon tried to get a better look. His body seemed to be pressed against the side of the building. He was almost certain he could push away, but he couldn’t do it right then. It was like the building was holding him, as if he were a refrigerator magnet.

The officer found his mom’s purse and Pigeon’s book. “Let’s collect these; the rest can be trashed.” Pigeon didn’t want the man to take his book, but the man had already slid it into the evidence bag. Pigeon knew it was an evidence bag — he had seen them before, when they collected Stevie after he got too sick to live on the street. They never saw Stevie or his stuff again. His mom had said that Stevie probably died in a hospital somewhere, because he would have come back if he could have. And now they were collecting his mom.

The screams inside Pigeon’s head felt loud enough to wake the dead. He didn’t want them to take his mom away.

“They’d collect me too if they knew about me,” Pigeon realized with a start. If he could keep from being collected, then he could find her. He would follow them and find her. The mental screams stopped, and Pigeon was able to inhale. “Just breathe,” he told himself. “One breath at a time.” His racing heart slowed a bit. “Stay in the moment. Stay in the moment.” He muttered the silent prayer his mom taught him.

He couldn’t be seen by the police. He needed to get away before one of them glanced up. Pigeon tried moving his fingers a little. His body gently moved a bit. This gave him the confidence to flap both his wrists—and that’s how he thought about it: flapping. Flying. It worked.

Pigeon cleared the drainage pipe. He moved up faster. Too fast! He bashed his head on the underside of a windowsill. The cop paused. Pigeon held his breath, but no one looked up. Why would they? Kids don’t tend to fly over dead people. Slowly, Pigeon floated all the way up and over the edge of the roof. He wrapped his arm around a pipe running along the edge so he wouldn’t float any higher, then he peered down from the roof.

An ambulance came, and his mom was loaded in. She no longer looked like his mom. Mom had smiled all the time, and she made little noises, and hummed, and moved. She had been so different from the thing that was being wheeled away. This thing didn’t look like a person at all. The left arm and fingers were stuck in a strange position as if they belonged to a store mannequin. The eyes were open and staring off into space. Instead of relaxing into the ambulance gurney, the body stayed stiff and looked so small. Definitely not like Mom.

Another car came. Three people in white masks and blue gloves gathered up all of their belongings and put them in big garbage bags. Mom and their nest and everything they owned were gone, just like that. It was like they had never been there. Like he had never even existed.

Pigeon leaned over the edge of the roof. It looked very far down. He wasn’t floating anymore and he had let go of the pipe. He still felt a tinge of that strange sick-in-the-stomach feeling, but it was almost gone. He could remember how it felt, but it was only a memory of a feeling. He tried flapping his wrists. Nothing happened.

He was alone on the roof. The ambulance with his mom had gone, and so had the people with the garbage bags. The policemen were still talking to each other, but they were clearly getting ready to leave. And the city was starting to wake up. Pigeon felt panic move up from his gut to his chest and head. He crouched low and allowed himself to cry quietly, hidden in the corner of the roof.

Suddenly, he heard a man whistle. Pigeon looked up—the man was just a few feet away from him. Pigeon willed himself to be invisible. I’m just a stupid bird on the roof. Birds sit on roofs all the time and no one cares.

“Hey!” The man was staring right at him. “How did you get up here? Did you climb the fire escape?” The man leaned over to look. The ladder was pulled up and locked. The kid hadn’t come up that way.

“Hey, I said, how did you get up here, kid? Are you by yourself?” The man looked around suspiciously, taking a few wary steps back toward the metal door in the roof’s center, which led back inside the building.

Pigeon tried to answer, but no sound came out. He could taste bile at the back of his throat, and more importantly, he could feel that weird pulling sensation in his stomach again. The man, apparently satisfied that they were alone on the roof, started toward him again. Legs numb and full of pins and needles from crouching for so long, Pigeon pushed up hard and swung over the edge.

“No!” the man screamed. “I won’t hurt you. Oh my God! Stop!”

But Pigeon was already over the side. He didn’t fall. He bounced off the cornice and flipped a few times in the air, but he didn’t fall. He tried making frog movements with his legs, like his mom taught him when they had gone swimming that one time in a lake. That seem to help stabilize him somewhat, and he stopped spinning. He still didn’t know how to move in a particular direction, but it didn’t matter very much at that moment. All he wanted was to get away from the screaming man on the roof.

Thrashing around in the air, high above Taylor Street, Pigeon tried to figure out how to control at least the direction of his flight. He started swimming the other way and managed to slow down a bit before hitting the building across the street. The impact was still hard, but at least he hadn’t smashed a window. The man on the roof had stopped screaming by then and was just looking. Pigeon needed to get out of there. He didn’t want the man to attract attention by shouting and pointing.

Pigeon felt pretty buoyant. He wasn’t going to fall, at least not yet. He used his fingers to pull himself along the brick siding and turned the corner away from the man on the opposite roof, out of his line of sight. He tried flapping again with his free hand while pushing away from the wall with his other. That didn’t work; he just got pushed back into the wall again.

Pigeon stopped moving altogether and gently hovered next to a window. Inside, someone was watching TV and making breakfast. Pigeon felt panicky. He didn’t want to see or be seen. He tried swimming with his arms again and kicked off from the building. This time he was able to get away from the building’s pull and glide out over the street.

Pigeon floated above Geary Street. Below, cars were moving in the early morning fog. Stores were still closed and there were very few people out. It was cold. Very cold. Pigeon shivered and felt himself rising another dozen feet or so. He was now well above most rooftops. He could see the giant Christmas tree in Union Square. They had just been there yesterday, he and his mom. Pigeon had wanted to watch the ice skaters glide around the temporary rink. Mom said that she would let him try it on Christmas Day. It would have been a good present. But it was closed and there wasn’t anyone there now.

Pigeon spotted a few street dwellers below, wrapped up in doorways. They were still asleep; it was still too early and cold to start the day. The shops weren’t opened yet anyway — no point in moving until they had to. Pigeon could tell them apart by their nests. Mel’s red and black sleeping bag was tucked into a corner of a souvenir shop; the pair of shoes placed neatly on the cardboard box to the left belonged to the guy from New York; and the collection of superhero toys in lots of small plastic bags was Jupiter’s.

Jupiter was a Jew named Peter. “Jew plus Peter, get it?” he’d said the first time they’d met. He allowed Pigeon to play with his toys sometimes, but only one at a time. Jupiter was okay. Mom even allowed Pigeon to hang out with him when she had to go away for a few hours to run errands. Jupiter would stay asleep as long as he could. He became a Silver Statue late in the afternoons, working the southwest corner of Union Square nearest the theater district. He said people gave more money when they were on their way to the theater.

Pigeon looked around. Macy’s looked festive: a giant red ribbon took up the whole side of the big building and each window was hung with a wreath. There were Christmas decorations everywhere. But what attracted Pigeon’s attention the most were the roofs. There was so much going on up there. From the street, one had no idea of the maze of pipes and giant fans, the tubing, the endless nooks and crannies. They looked very interesting. The Macy’s roof in particular was amazing. And as Pigeon looked at it, he started to gently float down toward it. On the inside, it felt like he was being pulled by a gut string. He could tell exactly which gut, too, if only he knew where each one was inside. His liver, maybe?

The roof was coming up faster than Pigeon liked. His left side still hurt from the collision with the building, and he didn’t want a repeat. He tried to frog-swim with his legs and flap with his arms. All the swishing around made him start to tumble. He was still descending, but now he couldn’t see exactly where. The sooner he figured out this whole flying thing, the better.

Mom would have known what to do, he thought. That was a bad thought — and Pigeon spun out. It was like his emotions and flying were tightly mixed. Strong feelings propelled him faster and made him more buoyant, but he lost all control over direction and speed.

The world twisted and turned. Windows, trees, lights, cars. Pigeon wasn’t even sure how high he was anymore, but the roofs had gone away. Thoughts were popping in and out of his head as fast as images. Someone will surely see me. Get out of my way, bird! Cool snow globe decorations. Please don’t let me hit the tree.

There was a bump, and Pigeon found himself sitting outside a window. Union Square was still below him, but he was at least half a dozen stories up, on the building around the corner from Macy’s. The ledge he’d landed on was wide, and would have been comfortable if not for the little nails sticking out in all directions along the entire edge. To keep the pigeons out, he noted. I guess they don’t work.

Pigeon adjusted himself off the nails and looked out. No one seemed to have noticed him. Relieved, he leaned back and closed his eyes for a bit. He needed time to think.

It couldn’t have been more than an hour since the police had taken away his mom and all their worldly possessions. He would have to find out what really happened. It was a weird feeling. On one hand, he was sure his mom was dead. She had looked so object-like, so lifeless when the police collected her. But it was also hard to imagine the world without her. He desperately wanted to talk to her about all that had happened — his flying, the police, her dying, the strange man on the roof, roofs in general, and the strange feelings that pulled at him and made him lighter than air.

Pigeon was very tired suddenly. He would just rest here for a while…

There was a rapping on the glass. A face was looking at Pigeon through the window.

Two: Letting Go and Holding On

Startled, Pigeon almost fell off the ledge. But something inside pulled him back; his new ability gave him an increased stability, like one of those self-righting toys that can’t be knocked down. He found himself face to face with the girl on the other side of the glass. He watched the girl’s eyes widen to the size of dollar coins.

“Are you all right?” she asked. Pigeon couldn’t hear her through the glass, but he could read lips well enough to get that.

“Yes. I’m fine,” he answered, exaggerating his mouth movements.

She looked at him a bit longer, then climbed the windowsill on her side to figure out the lock.

Pigeon stood up as well, but she frantically motioned for him to sit back down. He smiled and waited. She couldn’t do more than crack the window, but it was enough for sound to get through.

“Hey. I think I can pop it. Wait here while I get a fork.” She smiled and disappeared back into the room. Pigeon liked her.

When she came back, she stood on the window ledge and pushed a fork through the latch. Her face puffed with effort. “I think I’ll have to break the lock,” she said.

“Aren’t you going to get in trouble?” Pigeon asked.

“We’ll just close it afterwards.” She kept pushing harder. The fork bent. Then there was a snap, the lock popped out, and the girl fell backward into the room.

Pigeon pushed on the window, climbed through, and jumped down into a hotel room. The girl was sitting on the floor, rubbing her elbow.

“Are you okay?” It was Pigeon’s turn to ask.

“What were you doing outside my window?” She was looking up at him with big gray eyes, red hair falling down the shoulders of her pajamas in unbrushed wildness.

“I…” Pigeon wasn’t sure how he should answer that. Anything he said seemed likely to get him into trouble fast.

“Do you climb?” she asked. “My brother climbs. But even he isn’t stupid enough to climb seven floors up a sheer wall.” She looked him over. “And he wouldn’t be wearing that.” She pointed to Pigeon’s baggy jeans, gray hoodie, and old gray sneakers. Everything was slightly too big — Pigeon’s mom always said he’d grow into them.

“I…” Pigeon tried again, but closed his mouth. Never say anything unless you’re sure it’s the right thing to say.

“What’s your name?” the girl asked. “Mine is Ruth Kikkert.”

“Nice to meet you, Ruth Kikkert. I’m Pigeon. Just Pigeon.”

“Like the bird?” She looked over Pigeon again. “It fits,” she finally decided.

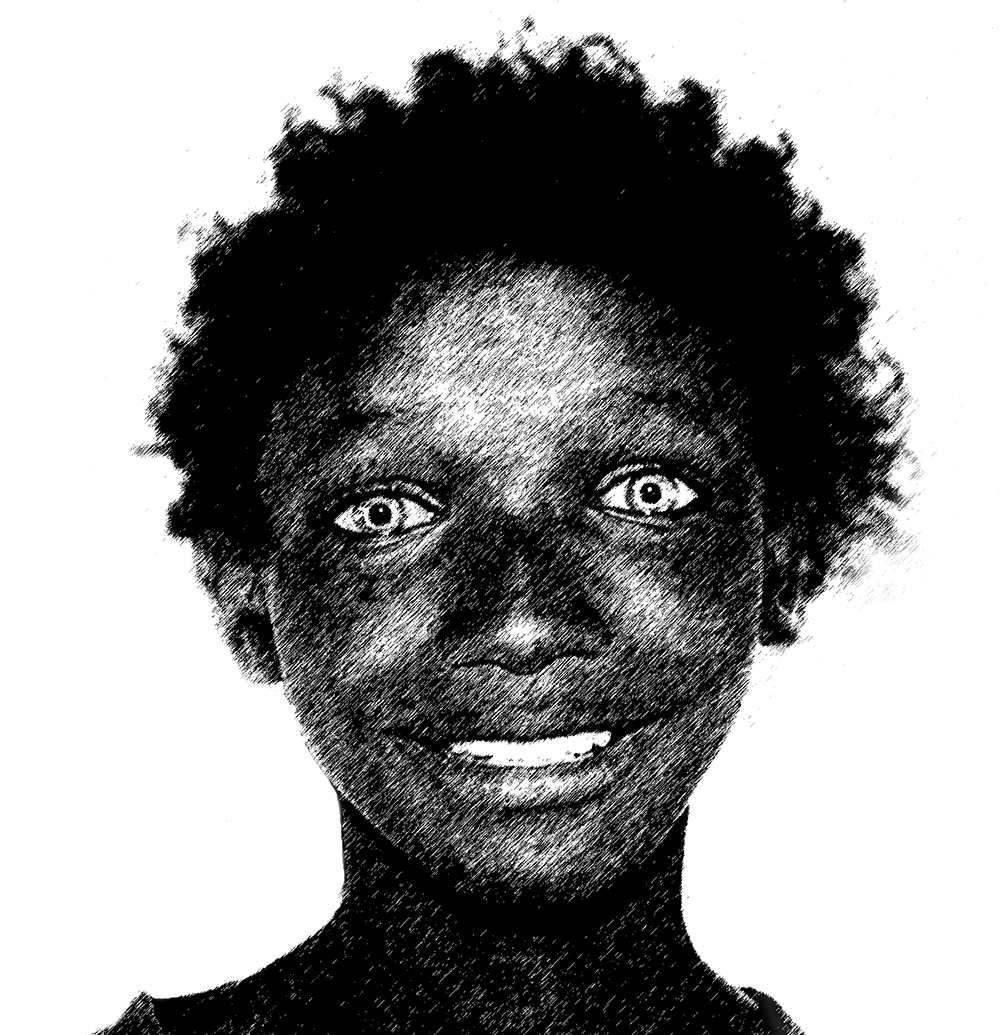

Pigeon was a bit small for his age, but wiry. His skin was medium brown with dark and light freckles all over, and his hair was a mess of wild curls sticking out in all directions.

His mom always said there wasn’t a point to even try to tame it. But the most startling feature of Pigeon’s appearance was his eyes, which were blue. Dark skin and blue eyes was an unusual combination, enough to always elicit a comment whenever Pigeon and his mom met new people. But Ruth didn’t remark upon it. Pigeon liked her more.

“Do you think I can use your bathroom?” Pigeon asked. He wondered if he looked different. Did flying change you? The bathroom would give him a few moments to compose himself in private. What was he going to tell her?

“Over there,” Ruth pointed. “This is my room,” she said, anticipating Pigeon’s next question. “My parents are next door, and my brother’s room is across the hall. But they all sleep late.”

“What time is it?” Pigeon asked.

“Almost eight,” Ruth said, looking over to the bedside table. “When you’re ready, do you want some food?”

“Yes, that would be great!” Pigeon marched into the bathroom. He carefully locked the door and looked around. It was an amazing place. All stone, shiny metal, and fluffy towels. It was even bigger than the family bathroom at the local homeless shelter, bigger than any room he and his mom had ever slept in.

Pigeon looked at his reflection in the wall-sized mirror. He still looked human, he decided. He did have big circles under his eyes and large patches of black soot on his face and on the shoulder of his hoodie. His hoodie also had a rip — must be from the collision with the building. Mom wouldn’t be happy, Pigeon thought, but there was nothing to be done about it now. He tried to wash up as best he could. When he was done, he looked himself over in the mirror again. Could be worse, he concluded.

“Bacon?” Ruth called through the door. It sounded like she was talking to someone on the phone.

“Yes, please.” Pigeon flushed the toilet, even though he hadn’t used it, and came back into the room.

“I like you better without the dirt,” Ruth commented. “Are you homeless?” she asked after she finished her visual inspection.

Pigeon thought about lying, but it seemed stupid. “Yes,” he replied.

“Would you like to take a shower and change into something clean before we eat? It’ll be about fifteen minutes before room service gets here.” Apparently she wasn’t satisfied with his level of clean. She looked him over again. “I think we’re about the same size, only I’m taller.”

“Not by much.”

Pigeon considered her. She was either his age or perhaps a year older. She was skinny, with long legs, so she looked taller than she really was. But he didn’t want to argue the point. Her hair was bright red and was nearly as wild as his own. And she was covered with freckles all over — face, neck, hands, feet. Everywhere Pigeon looked, Ruth was polka-dotted. She was barefoot and wore light green pajamas with little white flowers.

“My mom bought me these.” Ruth pulled at the material, noting Pigeon’s inspection.

“They’re nice,” Pigeon managed to mumble. The word “mom” was painful to hear.

He must have flinched. “Are you okay?” Ruth asked again. “Look, I’m not trying to pry into your personal life, but you did climb into my room.”

“I didn’t mean to, not really.” Pigeon still hadn’t thought of how to explain. “I just sort of ended up here unexpectedly.”

“Really? No one climbs up seven stories unexpectedly.”

“I know. But I did. I was trying to get to the roof of Macy’s.”

“Macy’s! That’s across the corner of Union Square. You can see it, see? There’s a big sign and everything.” Ruth was looking him over, trying to figure him out. “You don’t seem like you’re lying. Confused, then?”

“A bit,” Pigeon agreed.

“Okay, here are some sweatpants, a t-shirt, and some socks.” She pulled out a few things from a set of drawers next to the bed. “You’re welcome to my underwear if you like.”

“No thanks.”

“I didn’t think so. Go take a shower. I’ll put your clothes out for laundry, and you can have them back this afternoon, okay?” She made a wide sweep with her hand in his general direction.

Pigeon wasn’t sure he wanted to stay that long. But he didn’t have a better place to go. “Will this be okay with your parents?” He almost said “mom and dad,” but managed to stop himself in time.

“I won’t tell if you won’t.” She went over to the closet near the front door of the hotel room and grabbed a bag with “laundry” printed on the front. It was half full. “Hurry up or you won’t get yours back today.”

Pigeon took the laundry bag and the clothes she offered — they didn’t look too much like girl’s clothes — and went back into the bathroom. He emptied his pockets and put his three dollars and sixty-three cents onto the counter. To his money pile, he added a particularly large paperclip that he was saving, a pebble, a wad of napkins, and half a candy bar. That was all he had; the cops had all the rest. He didn’t even have any ID, although he wasn’t sure what ID he was supposed to have. His mom recorded important events about their lives — like his birthdays and height measurements — in a journal, but that probably didn’t count as an official document.

Pigeon stuffed all but his sneakers into the laundry bag, then shoved it out the door. He heard Ruth take it away. He quickly stepped into the shower and scrubbed. His mom always told him not to waste an opportunity to get clean. He thought of her and allowed himself to cry a bit. No one can tell in the shower.

Ruth pressed the laundry button on the phone, then pushed the now full laundry bag outside her door. The boy was clearly in trouble, she decided. He was way too young to be on his own. At some point, Ruth would have to tell her parents about him, even if he didn’t want her to. But, on the other hand, he never told her not to.

It was still three days before Christmas, and Ruth didn’t have any family obligations until Christmas Eve. She was allowed to go out by herself, as long she stayed nearby. She hoped that would be enough to help him somehow.

Ruth got dressed quickly and counted the money in her wallet. She had eleven dollars. She would need to get more. She could tell her mom that she was planning on doing some shopping on Grant Street, a touristy Chinatown right next to Union Square. She was sure she would be given some money for that, but she hated to lie to her mother.

Ruth’s heart-shaped face reflected every thought as she negotiated with herself about the plan for the afternoon. Her face was still scrunched up in concentration when Pigeon came back out of the bathroom, dressed in her clothes. She noticed he had been crying. That made up her mind.

“I was planning on walking around the neighborhood after breakfast. Would you like to come? Your clothes should be done by three or so.” She watched Pigeon for his reaction to her suggestions.

“I could just come back later,” Pigeon offered. He wasn’t sure he should stay, but he didn’t know if he was already committed by wearing Ruth’s clothes.

“School’s over, and I don’t have much to do. Do you?” Ruth pushed.

Pigeon didn’t have a plan yet. But he knew he had to figure one out before nightfall. Where was he going to stay? Was there something he should do for his mom? He wanted to ask Jupiter for advice.

“Well, you don’t have answer now. We can eat first…” There was a knock on the door. “Do you mind?” Ruth motioned toward the bathroom. “Go! I don’t want them to see you here,” she told him in a hushed tone, but with an exaggerated expression of exasperation.

Feeling slow and awkward, Pigeon slid out of sight. When he was hidden, Ruth answered the door.

“Thank you very much,” Ruth was telling the men who made the delivery. “Where do I sign?” She seemed very knowledgeable on procedures for dealing with room service. Pigeon was impressed by her poise. He couldn’t have done that. But then he’d never had the need.

“You can come back out now,” Ruth called him back into the room after closing and locking the door to her hotel room. “Don’t want anyone to just walk in on us,” she explained. “So, toast or muffins? Please don’t pretend not to have a preference. People have strong opinions about bread.” There was a large rolling cart with wonderful-smelling food under big, silver, bell-like lids.

Pigeon really didn’t care much one way or the other, but he was hungry. He pulled over a chair and set it up next to the cart and across from Ruth. “Muffin,” he decided.

“Good. I thought so. You look like a muffin man.” She placed two muffins on his plate. “Butter?”

“Yes, please.”

“That’s better. Now eat. I’m sure it will be a full day.” She looked at him. “We’re going out exploring. We have time to kill before your clothes are clean. And I’m sure you can show me all sorts of cool things, being a local and all.”

Pigeon wasn’t sure that the things he knew about San Francisco’s street life were the sorts of things Ruth was interested in seeing. “Actually, we moved here just this summer,” he tried. “So…”

“We?” Ruth didn’t miss much.

“Mom and I.” Pigeon’s voice reflected the strain he felt, and he got that funny feeling in his gut again.

“What?” Ruth was looking at him. “What did I say now?”

Pigeon held on to the arms of the chair — he was starting to lift off. “Nothing,” he managed finally.

“So you’re not on your own. That’s good,” she said. “You don’t have to be so nervous, you know. Just eat. Eggs are really good here. I didn’t know how you like them so I just got them scrambled. I hope it’s okay.”

“Fine, thank you.” But Pigeon made no move toward the food. His feet were completely off the floor now. He held on to the chair with all he had, straining against the strange force that was trying to pull him up to the ceiling.

“Are you trying to show off?” Ruth sounded angry. “Perhaps you’d rather have breakfast with my brother? You and Gabe can compare the size of your muscles.”

“It’s not like that,” Pigeon stumbled. To Ruth, it must have looked like he was doing a push-up off the armrests of his chair. His arms hurt from holding on so hard, but the upward tug was only getting stronger.

Then the unthinkable happened: he floated up to the ceiling, taking the chair with him.

Ruth jumped back and almost fell over her own chair as she leapt to her feet. “What? How are you doing that?”

“I don’t know.” Pigeon couldn’t control his panic. He was pressed against the ceiling now, still holding on to the chair, which dangled beneath him. “I didn’t know I could do this.”

Ruth recovered from her initial shock, and now seemed surprisingly calm.

“What’s the trick?” she asked. “Do you do tricks? Like a performance artist or a street magician?” She walked under him, looking for some hidden mechanism responsible for lifting the boy and the chair off the ground.

“I haven’t figured out the trick yet… I mean, it’s not a trick,” Pigeon started to explain. “I just feel this tightness in my stomach and up I go. I didn’t know I could lift a chair, too. That’s new.” Talking about it was reducing his sense of panic. He felt the chair sway underneath him, growing heavier like an anchor on a rope.

“Is this how you got to my window?” Ruth asked.

Pigeon nodded.

“You just floated up?”

Pigeon nodded again.

The chair started to descend, and Pigeon with it. He was still feeling the tug at his gut, but it was being overpowered by gravity. The chair touched the floor, but Pigeon was still hovering above it.

Ruth came closer and slid her hand between Pigeon and the seat of his chair. “Hmm. Give me your hand,” she ordered.

“It might not be a good idea.” The panic started to well up again, and the chair lurched. Ruth stepped back.

“Let’s try anyway,” she said. “Keep one of your hands on the chair. I’ll hold on to you with one hand and the chair with my other. Okay?”

There didn’t seem much more to lose at this point, so Pigeon did as Ruth instructed. Ruth would be heavier than the chair, right?

“It feels like you’re pulling on me,” she said, her hand stretched up. Pigeon was lying sideways in the air, parallel to the ground. His hand holding on to the arm of the chair was lower than the one holding hands with Ruth.

“Can you lift me up?” Ruth asked.

“Maybe if I let go of the chair. I don’t think I can lift you and the chair at the same time.” Pigeon tried pulling the girl up a little. “I don’t want to let go of the chair.” He wanted a solid point of attachment to the ground. Well, semi-solid.

“Yes, that might not be a good idea,” Ruth agreed. “Can you stop now?”

“I’m not sure.” Pigeon closed his eyes and tried. He wasn’t exactly sure what he should do, but he focused on the feeling in his gut. He tried to relax it away, the way one might try to relax away the hiccups.

“That’s good,” Ruth encouraged. “Keep doing whatever you’re doing.”

Pigeon felt the floor under his feet again, and he let go of Ruth’s hand. “Thanks,” he said.

“For what? Never mind. How did you do that? How did you fly?”

“Not sure. But it feels like a sick feeling in my gut. And the stronger the feeling, the higher I seem to go up. It happened this morning,” Pigeon added.

“What? Flying?” Ruth asked.

“Yeah. It…” Pigeon almost started telling her the whole story, but held back.

“Are you an alien? A mutant, like the X-Men? It’s okay to tell me. I won’t tell a soul,” Ruth promised.

“I’m human.” Pigeon hesitated. “At least, I thought so until this morning.”

“What happened this morning?” Ruth touched him on his shoulder as if to reassure herself.

“My mom died.” Pigeon finally decided to go for it and tell her everything. He had to tell someone, and he liked Ruth. He really liked her.

“Oh.” Ruth felt at a loss for words, which was unusual for her. “Is there something I can do?” she finally asked.

“I don’t think so,” Pigeon replied. “The cops collected her this morning. I watched the whole thing from the roof. I don’t think they know about me.”

“I see.” Ruth had never met anyone who had seen their mother die. And she herself had never even seen a dead person. Her grandfather had died a few years ago, but she never saw his body. Now, Ruth wasn’t sure what was the appropriate thing to say. This wasn’t something she’d ever prepared herself for. “Perhaps we should eat. The food is getting cold.” Food she understood. And she also knew that food made people feel better. There was always food after funerals.

“Okay.” Pigeon sat down again in his chair. “The eggs are cold.”

“Sorry. Do you mind?” Ruth asked.

“No, not really. I’m fine with cold food.” Pigeon moved his fork around on the plate. He decided that he should eat. Never waste food, Mom always said.

Somehow, one forkful after another, both Ruth and Pigeon finished up their breakfast. They ate in silence — there was a lot to digest. Once in a while, Ruth would peek under the table to check that Pigeon’s feet were still on the floor. Pigeon pretended not to notice.

Finally, after finishing her tea and orange juice, Ruth found the courage to ask Pigeon a few questions. He seemed so lost, yet so determined. She just wasn’t sure what exactly he was so determined to do. They’d already established that Pigeon didn’t know much about his flying abilities, but that topic seemed better suited to experimentation than to questioning. And Ruth had already carefully planned out the experimentation while eating her breakfast.

“What happened to your mom this morning?” Ruth asked, figuring she might as well go for the hard question.

Pigeon was expecting it; one didn’t casually drop “My mom died this morning” and not expect a follow-up. Over breakfast, he’d made up his mind that Ruth was a good person to talk to about his mom.

“She died this morning, I think.” He adjusted his position and made sure both of his feet were firmly planted on the floor. Ruth looked down to make sure as well, and met his gaze afterward. “I’ll tell you if I start feeling it again,” Pigeon reassured her.

“I think I would notice.” One of her eyebrows went up in the air.

“I suppose so.”

“So tell me what you know.” Ruth looked around the room. “Do you want me to take notes?” She nodded toward the hotel’s writing supplies by the bed. “I mean, if you’re not sure, we should create a timeline of all the events, don’t you think? That way we can find clues.” She got up and got some paper with the hotel’s logo and a pen. Ruth planned to approach this scientifically.

“Okay,” Pigeon agreed. She looked so purposeful and ready, and it might be a good idea to record all of the facts while they were still fresh in his mind.

“Do you want me to ask questions? Or do you want to just tell the story?” Ruth prodded.

“Why don’t I tell you what I know and then you ask questions,” Pigeon replied, and considered where he should begin. “She… my mom said she was tired and cold, and so we went to make our nest early. She fell asleep right away.” Pigeon recalled his mom’s heavy breathing next to his back while he was reading. “I fell asleep a few hours later.”

Remembering lying next to his mom felt both good and scary. He felt the tug at his gut and tried to smooth it out. He didn’t want to be interrupted by another bout of flying. He wanted, needed time to think things through — and talking about it with Ruth helped. So he carefully recounted all the events of the morning up to his face-to-face encounter with Ruth. He felt her staring at him each time he paused, but she took what looked like good notes, with indents and bullet points, like a proper outline. Ruth’s handwriting was very good, too. Mom would approve, Pigeon thought.

“How are you feeling?” Ruth asked. “Do you feel that tug at your gut now?”

“A little, but talking with you makes it more manageable, somehow,” Pigeon answered. He focused on his insides and examined the strange sensation. It felt like a round ball with a rubber band attached to it. He could mostly ignore the ball part as long as there was no pull. But once the pulling started, he had a hard time not thinking about it. And now that he was thinking and paying attention to it, the tug grew.

“Your feet are off the ground,” Ruth remarked casually. She seemed so calm and accepting of the whole thing. Pigeon marveled at her composure once again.

“I think it was because I was looking it over,” Pigeon said.

“Like in your mind’s eye or something?” Ruth asked.

“Yeah.” Pigeon admired her ability to understand so easily things that were so hard. “I can almost draw what it looks like, even though I know it’s just a feeling. Strange, isn’t it?”

“The whole flying thing is way strange,” Ruth noted.

“Well, yes,” Pigeon agreed.

“Did you ever feel this ball and rubber band before? I mean, before this morning?” Ruth asked. She was ready to write down his answers.

“I’m just not sure.” Pigeon felt frustrated by his own uselessness.

“So no nighttime flying? While sleeping? I mean without your knowledge?” Ruth pushed on.

“I don’t know!” The chair moved.

“Hey. Relax.” Ruth motioned him back down, as if it were so easy.

Pigeon focused on his breathing, the way Mom taught him. Meditation was a good skill, she always said.

“Good. Good,” Ruth encouraged him.

Pigeon felt his feet return to the solidity of the floor.

“I’m not sure we can just wander outside.” Ruth was looking at Pigeon, watching for a reaction. “What if you just take off again? It’s daylight now—people would notice.”

“But I can’t just stay here.” Pigeon wasn’t sure what to do. His plan had been to find Jupiter and talk to him. But now that didn’t seem like a good idea. Maybe he could just hide out on a roof somewhere?

“You can’t just run away.” Ruth interrupted, as if she could read his mind.

“But your parents…”

‘I agree, it would be hard to hide you here. At least for a long time.” Ruth’s face was scrunched with concentration. She supposed they would have to tell her parents eventually, but until they knew more, she didn’t think it would be a good idea. Her dad would just call the police — because that’s what normal people would do. “I got it!” she exclaimed. “We’ll go to my grandma’s!”

“Why?” Pigeon didn’t like the idea at all. He started to regret telling Ruth.

“Look, Pigeon. You’re what? Eleven?”

“Twelve,” Pigeon lied. Ruth gave him a look. “Okay, almost twelve. But what does that have to do with anything?” He was feeling defenseless and helpless — not a good combination, and now even dangerous.

“Think about it,” Ruth pushed on. “You can’t live by yourself out on the streets. I don’t even think it’s legal. They’ll take you away and put you into the system.” The way Ruth said “the system” made Pigeon shudder. No, “the system” wasn’t for him.

“See?” she continued. “You agree with me.”

Pigeon wasn’t sure what he was agreeing to, but he let Ruth go on. He figured she would anyway.

“Grandma wouldn’t rush to get the authorities notified. We can ask her to take you in–”

“What?” Pigeon didn’t want to be “taken in” by someone’s grandma or by the authorities or by the system. He looked at Ruth and saw her standing way below him with her arms crossed.

“Calm down, Pigeon. And come down,” she commanded. The novelty of his floating ability had worn off pretty fast, Pigeon noted. “We need to have a strategy,” she said.

“We?” When did this become a “we” thing?

“You came through my window, remember?” Ruth reminded him again. “But the most important thing is that we need help. You need help. And our options are limited. Do you want to go to the police?”

“No.”

“I didn’t think so. At least not yet,” Ruth hedged. “And you’re right, we can’t stay here: the hotel will notice, or my parents or my brother. We need a safe place for you.”

“But your grandmother’s? Where does she live?”

“She’s just a few blocks from here, at the Palace Hotel,” Ruth said.

“A hotel?” Pigeon didn’t see the advantage of moving from one crowded hotel into another.

“It’s different.”

“How?” Pigeon asked.

“You’d like her,” Ruth assured him instead of answering his question. Her grandma was different, no matter how you defined that. For the last fifteen years, she had lived in one of the top-floor suites at the Palace Hotel. Madam Toad, as she liked to be called — Ruth’s grandmother took a very liberal English translation of their Dutch family name “Kikkert” — was a world traveler and had “seen a thing or two,” as she was very fond of saying. If anyone knew what to do, it would be her, Ruth decided.

“Now we just need to figure out how to get you there.” Once Ruth made up her mind, she usually followed through… sooner or later.

“Ruth, I’m sure your grandmother is a very good person, but…” Pigeon was far from convinced.

“Look,” Ruth interrupted Pigeon. “We’re both just kids. Sooner or later an adult needs to step in and help us figure this out. And I’m pretty sure most adults won’t be very understanding. But Grandma isn’t like a regular adult. She’ll listen, and then she’ll help.”

Pigeon just looked at her. He found it hard to say “no” to Ruth.

“Just trust me. No one lives in a hotel for over a decade. I mean, normal people don’t do things like that,” Ruth said.

Pigeon considered that. “Is she very rich?”

“Yes. But that’s just part of it. She’s just…” Ruth searched for words to describe her grandmother. Madam Toad stood out wherever she went, although lately she had been more sedentary. Her suite was filled with artifacts from her many adventures. (“Artifacts” was a good word to describe her varied collection of stuff, Ruth thought.) “I’ve been everywhere and done everything,” she’d told Ruth on more than one occasion. That wasn’t true of course, but she did have a lot of experiences. Ruth hoped that perhaps Grandma had heard of something similar to Pigeon’s flying ability happening to someone else. In Africa perhaps? Or Siberia? Or some other faraway place? Pigeon couldn’t be unique. Very few things were unique in this world. Well, except for all of us, Ruth thought.

Finally she told Pigeon: “Grandma is just different. Trust me. She’ll know what to do. And if she doesn’t, then she’ll know someone who does.”

The way Ruth said it made Pigeon believe it. Reluctantly he agreed to go. And as he did so, he slowly descended back down to the carpet.

“That’s better,” Ruth approved. “Now we have to find a way of getting you across Union Square and down to the Palace — while staying on the ground.”

As Pigeon visualized the journey, he felt his gut tighten.

“No you don’t!” Ruth grabbed him and pulled him back down. “You’ll have to concentrate and think of puppies or something.”

That made Pigeon chuckle, and he floated back down.

You can buy “Pigeon” on Amazon (and other places) here.

If you like the story, please consider leaving a review and tell your friends!