ProLog

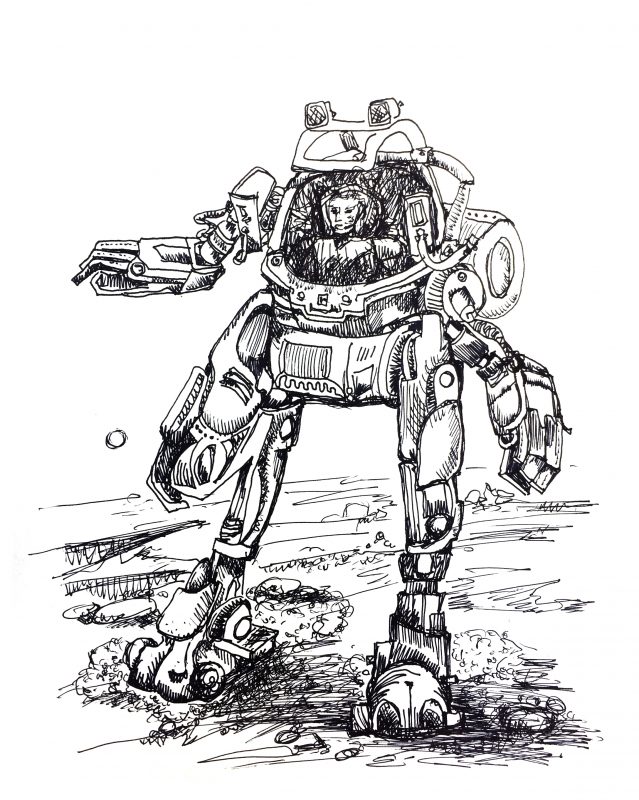

“The exton controls are not responding!” Marc shouted into his exoskeleton spacesuit helmet.

His exoskeleton was the heavy-duty dirt-and-boulder-mover type. Move a ton with exton. Right now, Marc was really just an intelligent bulldozer with life support. But the suit had disconnected from his D-tats, the personal computing device tattoos embedded in his lower arms and jaw, and his directional controls were busted. Now his exoskeleton acted with a mind of its own, moving him away from the construction site and out into the open Martian landscape. He needed to get back to the Malfy–an affectionate acronym for Martians Live Free, a city-sized habitat being built for the next wave of planetary immigrants.

“Marc?” his SB responded from the inside Malfy’s operational center. “What’s on the fritz this time?” Every contractor working outside was in constant communication with a personally assigned safety buddy. “I can’t seem to toss the controls over to my side.” In an emergency, Marc’s SB could take over the controls of his exton and bring him in, even if he was unconscious.

“I’ve got nothing!” Marc was more irritated than scared. This was his second equipment failure in as many months, and their group of union builders had reported three more to the management since the start of the project about two hundred days ago. It was always the same MO: at the end of a shift, the movement controls failed to respond to their operators’ commands, taking the builders out into the desert; and yet, after the rescue when the equipment was checked out, the engineers found nothing wrong with the extons. The first time it happened to Marc, he was even accused of faking the failure to get extra time off for hazardous conditions. As if construction work on Mars wasn’t dangerous in and of itself. Fortunately, Marc’s supervisor made everyone carry extra oxygen and a spare battery pack after the first few incidents. Just in case. Inconvenient for sure, but it was better than being stuck out of breath without a heater among the Martian dunes in minus 125 degrees Celsius.

“Send someone out to get me,” Marc said. “It’s an official request.”

“Are you sure, Marc? You know if they don’t find anything again—”

“I’m telling you, I’ve got nothing. Everything is dead on my side.”

“Yeah, mine too,” Marc’s SB agreed. “I’ll get Greg out there. But he won’t be happy. He just got his exton off and you’ll be cutting into his three days off period.”

“Tell him that I’d go if it was him out here. And tell him to hurry up about it.” The earliest he could expect Greg to arrive would be at least an hour, probably more–it took time get these darn things on.

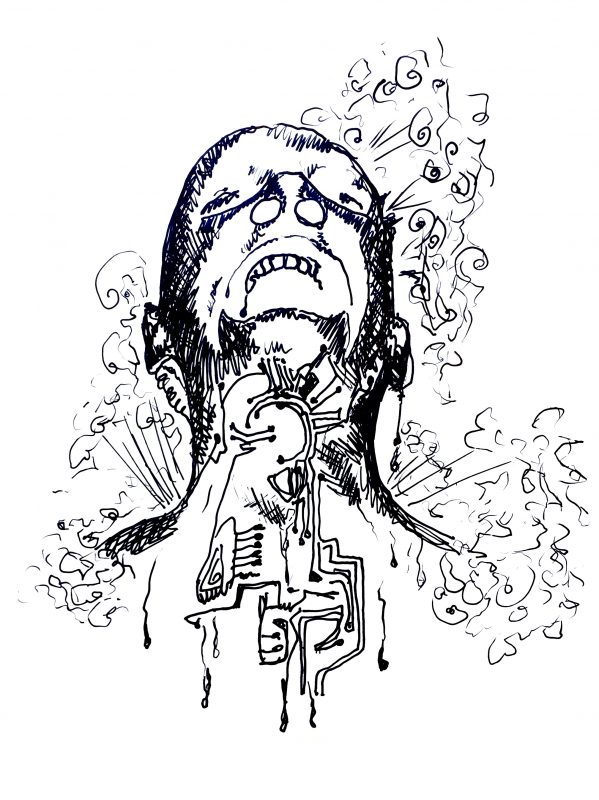

Marc felt funky. His D-tats itched like crazy, probably from all of the energy pushed through them to try to reconnect with his exton. And now his comm was down, too. As soon as he’d gotten over the rim of the crater, he’d lost touch with his SB.

It was lonely out here in the Martian landscape with no one to talk to and all the human structures obscured from view. Marc could only look ahead–his suit didn’t allow him to turn his head–and before him stretched miles and miles of nothing but rust sand and red rocks underneath a yellow sky. Someday this would be paradise, but Marc didn’t expect to live that long. Still, it was decent pay, and the benefits were great. And, most importantly, all the construction workers were to be awarded a family subdivision inside the new MLF. Marc looked forward to moving his wife and a new kid he’d never seen out here from Luna Colony. Kids should run around on the surface of a real planet, his mother always said. In a few years, Marc would make his mother’s dream a reality right here, on this dusty red rock. And when he did, he would be able to tell his kids that he built this place with his own hands. He would point to a boulder and say, “See that rock? Your daddy placed that rock.” It was a satisfying thought…if only the equipment worked right.

He tried to will his suit to obey. Heat erupted around his jaw and down his neck. It took him by surprise–not an emotion he was used to. The off-world building crews went through years of training, and part of that training involved controlling one’s thoughts. Spend too much attention on extraneous thoughts and emotions–like surprise and worry–and space got you. Cognition was a limited resource.

This fact about human nature was drilled into Marc, not just during training but from an early age. All Luna Colony children learned to focus and control their attention. Those who couldn’t didn’t make it to adulthood. It was different there now, in those modern Luna Live Free habitats—Elfys. But when Marc was young…

“Ahhh!” The scream seemed to rip itself out of Marc’s throat without his conscious control. Pain twisted his arms inside his suit. He felt himself hyperventilating. Something was seriously wrong with him, not just with his exton. The horror of that realization hit him hard as the exoskeleton kept marching him inexorably farther from the base. He smelled cooked meat. It took all his willpower not to think where the smell was coming from. The life support systems should have noted his elevated heart rate and responded.

Since his D-tats weren’t working, Marc tried to blink commands directly into the suit. He drilled down several menus and selected a painkiller injection. He needed to get himself under control. Rescue was still at least thirty minutes away.

Sweat trickled into his eyes. It was difficult to see now. He felt cold and yet heat burned his arms, neck, and jaw. His teeth felt out of alignment. There was a constant buzzing in his left ear, different in tone and structure from the one in his right. But at least it was something he could focus on. He poured himself into the strange, asymmetric tinnitus. Bzzz, bzzz, swish, bzzz, bzzz, swish…

“I found him unresponsive.”

Greg sat in front of a board of inquiry. Marc’s death was the first among the Martian chapter of the Off-World Builders Union this year. Given that Mars was deemed a relatively low-risk environment, the death had attracted extra scrutiny from both the union leaders and the insurance representatives for the Martians Live Free project.

“Are you saying Builder Mark Kelly’s communications were out? Or was he unconscious when you found him?”

“At first it wasn’t clear, sir,” Greg testified. “The exoskeleton continued to walk into the desert and wouldn’t stop until I caught up with it and patched into it directly.”

“So the comm was completely out?”

“Yes, sir. I wasn’t able to control the exton from a distance, and Marc lost his communication a while before that.” Greg wiped the sweat from his forehead. He hated answering stupid questions. Everyone already knew what had happened. Marc’s D-tats had fried from some bad connection to his equipment. Shit happens. Get over it. Move on.

The interrogation went on for another hour, but at some point, even the insurance representative recognized that Greg had nothing more to add to the report he’d filed with the union. The conclusion was that this was a freak accident caused by improperly implanted personal computing device tattoos a decade earlier. The Luna Colony medical board was granted jurisdiction over the case.

Chapter One

“Sentient life’s colonization of the Earth is fractal. Even within a single ecosystem, there are many species that possess intelligence and self-awareness. But only one species becomes dominant.”

Professor Volhard took a theatrical pause here. Everyone in the audience knew where she was going with this, but it never hurt to add drama to a presentation.

“Obviously I am talking about humans. We are not the only intelligent, self-aware species on our planet–but we got lucky. We were blessed with favorable initial conditions, and our dominance was almost guaranteed. Lack of luck tends to permanently retard progress. Dinosaurs’ loss is our win.”

There were a few chuckles from the audience, but no big laughs. Varsaad Volhard sighed inwardly and moved on. She never knew how the lay audience would react, but this was all part of doing the book-selling lecture circuit.

Vars was tall and skinny with short, unruly, dark red hair and glasses to match. She looked a bit like a stick insect in her black pants and black sweater. For the tour, she was trying to dress more interestingly than normal–per instructions from her publisher–and so had added the bright orange scarf that her publisher sent in the mail. The instructions that came with the scarf told her to wear matching orange shoes, but Vars didn’t own any orange shoes, so matching black was as good as it got.

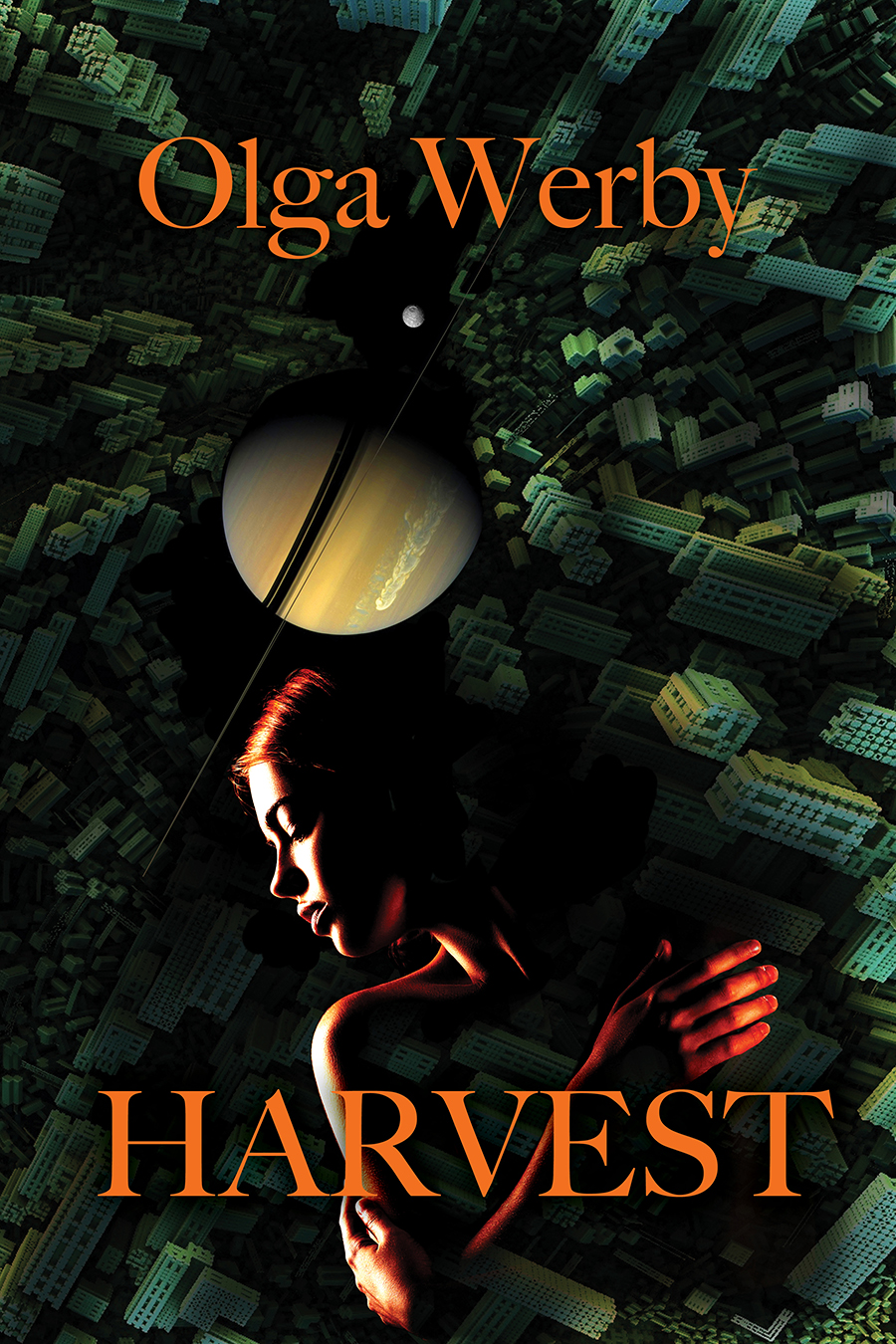

She hadn’t failed to notice that the cover of her book–Luck & Lock on Life & Love: The Human History of Conquest of Resources on Earth, Luna, and Beyond–had the same color orange titles as the scarf. Her agent or someone in the office was obviously trying. Vars made a mental note to figure out who that was and thank them.

Vars talked for a while without paying attention to what she said–that was a gift that came with giving the same talk for the hundredth time. Fortunately, she was almost at the end of her book tour. Two more lectures and she would be done. She could go back to teaching and research–get her life back. This nomadic lifestyle wasn’t for her. But before she got out of there tonight, Vars still had one more surprise argument for these people: a defense of space exploration.

She looked into the dark void in front of her. The stage lights made the hundred people in the theater disappear from view–a plus for a shy researcher. And she was a true believer in the “what you can’t see can’t hurt you” principle. Not only had she opted out of vision-correction treatments, she regularly taught without her glasses, leaving all but the front row of her classroom a Monet-like blur. The trick worked well to relieve her agoraphobic anxiety.

“So, what are the prerequisites of space travel?” she asked.

There were a few shout-outs from up in the gallery–the cheap seats usually occupied by students. “Civilization.” “Faster-than-light travel.” “Aliens.” They were on the right track, even if their sources were limited to science fiction movies. But Vars was an evolutionary socio-historian, and that meant she was trained to look both into the future and the past. She liked to think that her ideas about possible human future scenarios were well informed by historical precedents and intelligent extrapolations of cultural trends–meaning she wasn’t just talking science fiction here.

“Let’s start with something simple,” she said. “Time.” Time was never simple, but people always assumed it was. Everyone had experience with time, so everyone felt like they were experts on the subject. “Humans have a relatively long lifespan for a mammal. And we have the longest childhood of all animals.” Well, that was true now. Neanderthal kids had enjoyed a longer childhood, but Vars didn’t want to complicate things further. “Not only are we able to learn a lot before we plunge into adulthood,” Vars continued, “we also have the time to use that knowledge. I’m sure we would all like to live even longer, but nature has ensured that we live long enough to transfer wisdom from one generation to the next, so our species can build on that, expanding our collective grasp of how the universe works. Each generation stands on the shoulders of all those that came before. Without a sufficiently long lifespan to learn and apply that collective mastery, space travel would just not be possible.”

Vars tried to peer into the audience to check that they were still with her.

“So why not elephants or whales, you might ask. Both species live a long time and spend a significant proportion of that life as children.” Vars didn’t wait for answers. “Unfortunately, neither were lucky enough to evolve hands. Even the elephant’s prehensile trunk can’t compare with the nimbleness of human fingers. And whales have the additional disadvantage of living in an underwater environment. These are significant handicaps to developing space travel. So again, humans got lucky. We evolved to live on land, and we have the right appendages to be able to tinker with objects in our environment. To bend it to our will.”

“Language!” someone screamed out of the dark.

Vars smiled. Language came up over and over again at each of her lectures. “Yes, language,” she said into the darkened auditorium. “It’s been said that language is the ultimate tool of mankind. Its greatest invention.” There were sounds of agreement from the audience. “But are we the only species on Earth to possess language? Sure, human languages are incredibly sophisticated and versatile, far more so than those of any other species we have encountered to date. But until a few decades ago, we didn’t even believe that there were nonhuman languages here on our planet. Now, of course, we know better. Dolphins, elephants, and even some birds have been observed using rudimentary languages unique to their species.”

Vars stopped to listen to the audience. There were murmurings of assent, but also a few mutterings of rejection. The idea of animals inventing languages was very new still, but it was no longer controversial among her colleagues. Of course, politics was always way behind science. If humans were to widely acknowledge that dolphins communicated via language, then we might also have to recognize them as having some legal form of “personhood”–and that just wasn’t tenable in the current political climate.

The dissent told Vars what proportion of the audience held human-centric views. It was about forty percent or so, judging by the noise. That was about average for this part of the country. In places like Berkeley, California, only one or two people in the audience dared to express such backward opinions loudly enough to be heard on stage. Most dissenters kept quiet, she knew. People were herd mammals, after all, and needed to be surrounded by others with similar views. That was how social echo chambers worked in the age of mass e-media.

“Language,” she said, “particularly written language, is essential to passing information from one generation and one community to the next. Written language saved us from having to invent things over and over again–”

“Oral traditions!” someone yelled.

“Oral traditions are fantastic for capturing and communicating culture,” Vars replied. “But they are lousy for transmitting technical information. There is no oral tradition of calculus.” There was a murmuring of agreement. Good. “And before someone brings up apprenticeship, let me just say that I’m a believer in learning while being embedded in a community of practice. We see such educational approaches in species other than our own. Chimps routinely teach their offspring how to fish for termites with specially made twigs. Birds teach their chicks how to hunt and which foods are good and where they can be located. Cerrado, a species of monkey from South America, use giant hammer rocks to break tough palm nuts over carefully selected anvil boulders. It takes years for the youngsters to learn how to select just the right hammers and anvils and to perfect the technique for bashing open the nuts. So yes, apprenticeship works–but it has its limits. We are the only species on Earth to develop other intentional ways of passing on knowledge. Without written information, we wouldn’t be in the process of colonizing Mars, or mining the asteroids, or having permanent bases on the moon.”

Vars gave the audience a few seconds to absorb this. She wasn’t done having fun with them yet. “But before written and oral language traditions, before the apprenticeship form of passing knowledge from generation to generation, there was another way. Nature’s way. Evolution’s way.”

She stopped, giving her listeners a moment or two to guess the answer. Some nights, the audience got it almost immediately; other nights, there wasn’t a clue in the house. Tonight, there was only silence.

“Evolution couldn’t wait for humans to invent language. Survival depended on passing some information down the chain of generations.” Well? Still nothing? “I’m talking about instincts, of course. Our drive to mate, to reproduce, to protect our children. Our will to survive against all odds. We’ve all experienced, or will experience, these instinctual needs. It’s in our DNA, so to speak. But that’s not the only hard-coded knowledge that we pass along to our offspring.

“I will focus on humans here, because that’s what I wrote my book about. Which reminds me: I will be signing copies in the lobby right after the end of the lecture. I’m required to say this by my publisher.” There were a few chuckles. Good. Vars hated dull groups. It was hard to speak without feedback. “Agoraphobia and claustrophobia, fear of dark places and of heights, ophidiophobia and arachnophobia, instinctual disgust of bodily fluids–blood, urine, pus, feces–all of these are innate for us humans. We are born to avoid tight places and grand expanses. We naturally avoid snakes and spiders even if we’ve never seen or heard of them before. But we have also learned to overcome these fears. We had to if we were going to go into space. Our spaceships are extremely cramped, and they float in vast expanses of space. Astronauts are forced to recycle their bodily fluids and to no longer be afraid of extreme heights and absolute darkness. Although I may never overcome my fear of snakes and spiders…” She shivered dramatically and earned a few more laughs. “And perhaps, one day, we will meet other explorers out there. And we might have more innate fears to shed.”

Vars talked for another quarter hour about the importance of different sensory apparatuses and the need for access to easily extracted raw resources, but it was getting late, and she could feel that the energy had drained from her audience. She was tired, too. She needed to catch a redeye tonight and try to squeeze in a few more hours of sleep before another lecture tomorrow.

Before she was even aware of it, there was hearty applause, and then it was time for smiling, handshaking, and book signing. She’d come to learn that the only people who still bought paper books were the ones who attended these book tour lectures. She was grateful to all of them, and yet she couldn’t wait to get out of there.

“Dr. Volhard?” The voice was a nice soft baritone. “May I have a moment of your time after you’ve finished autographing?”

Vars raised her head, a fake smile plastered on her face, and tried to identify the speaker. There were still half a dozen people waiting, each clutching a copy of her book. But none of those was the speaker. So she went back to signing, and soon enough, like magic, it was done. She rubbed her wrist, which had started to cramp up, and slid the contents of the table–brochures, pens, and leftover business cards–into her bag. She would deal with sorting it all out later.

“Coffee?” the baritone asked again. “I know you take it with sugar and milk. But I wasn’t sure of the proportions.”

Vars looked up again. A tall, slightly graying man in rimless glasses with a slight yellow tint was standing in front of her, holding a recyclable coffee cup. He was dressed in jeans, a dress shirt with no tie, and a wool jacket–easy elegance, her literary agent would call it. She tried to do something similar for these lectures–approachable, smart, and interesting were her original goals. But at this point in the lecture tour, all she could hope for was clean, awake, and present. Dressing in all black helped.

“I beg your pardon,” she said. “Do you have a book for me to sign?”

“That would have been lovely,” the man said, “but I bought an e-version of your book.”

“I can sign your data pad,” Vars offered. She still didn’t take the coffee from his extended hand. And she wasn’t planning to.

“What a lovely idea.” He smiled. “Do you mind if we talk a bit? I know you’re tired–”

“And I have a plane to catch.” Vars spoke more harshly than she’d meant to; the man did buy her book, after all.

She tried to go around him, but he wouldn’t budge. She looked past him for a security guard at the door. Shouldn’t someone be getting everyone out of here? Perhaps escorting her to a taxi? She was getting annoyed and a bit alarmed.

“My name is Ian Rust,” the man said.

“Dr. Vars Volhard.”

“Of course.” He smiled again.

“I really do have to go, Mr. Rust,” Vars insisted. She tried to push past the man, her suitcase ready to roll behind her.

“The thing is, Dr. Volhard, we really need your expertise as soon as possible,” Rust said.

“Sir, I’m an evolutionary socio-historian. My direct expertise is rarely required on an emergency basis. Contact my university office, and I’m sure I would be able to fit you in during one of my ample office hours after I get back.”

“Ah, but there are exceptions,” he said. “We’ve read everything that you’ve published–”

“Everything?”

“Everything. And you have a unique set of expertise that my team at Earth Planetary Space Agency urgently requires.” He pulled out his EPSA credentials. “Our car is waiting outside, Dr. Volhard. Won’t you please follow me? Do you mind if I call you Vars?”

“Sure,” Vars said automatically.

“Then please call me Ian.” He handed the coffee to her.

EPSA was the umbrella agency that had taken over for NASA, ESA (European Space Agency), ASA (Australian Space Agency), and JAXA (Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency). So it wasn’t entirely “planetary”–China and Russia still ran their own space exploration programs–but it was the largest and best-funded agency, and it was the one that was actively pushing the Mars colonization program and comprehensive exploration of the solar system.

Vars had always dreamed of working for EPSA, even as a girl. But somehow, somewhere along the way, her academic career had veered into anthropology, and then evolution, and then…well, here she was. The evo devo diva of anthropology.

And now she was riding down the dark, empty streets in the back seat of a black driverless car, with Dr. Ian Rust, head of the exobiology research team at EPSA, sitting by her side.

Chapter 2

Vars slept on the plane…or tried to. She was too confused, too keyed up to really sleep. That coffee might have been a mistake. Ian said that he couldn’t tell her anything until they arrived at his EPSA office in Seattle, which was conveniently her own hometown where she lived with her dad. The man just smiled a lot and talked about how much he had enjoyed reading Vars’s new book.

There was a strange edge to their interaction. If Vars hadn’t believed Ian’s credentials, she would have bailed on him a long time ago. Even so, she felt like she was being kidnapped. And, in a way, she was. She’d had to cancel the last two lectures of her book tour and apologize to her agent over and over again. Ian had promised that EPSA would send an official excuse letter, but Vars still felt like she let her agent and publisher down.

They landed at a general aviation airport, and another black car whisked them to EPSA’s headquarters, just outside of Seattle’s city limits. She was taken to a conference room on the top floor of the EPSA science building, which Ian called the “tree house.” She immediately understood why–it was surrounded on all sides by a balcony planted with a row of trees and some shrubbery. It was quite nice, but Vars couldn’t enjoy it; she was simultaneously exhausted and adrenalized. It was just a matter of time before she crashed.

She must have looked it, too, because someone handed her a very big, very steamy cup of coffee. She sipped it gratefully, completely oblivious to how she came to be holding it. It was still very early in the morning, way before Vars even liked to get up, much less attend a meeting.

About a dozen EPSA people joined her and Ian around the conference table. Vars noticed that several paper copies of her book were laid out; some even looked read, with cracked spines and dog-eared pages.

“So,” she said to Ian. “Is now a good time and place for you to tell me what this is all about?”

“Now is perfect,” Ian said with a big smile. “We are very grateful to have you with us today, Dr. Volhard. This is my exobiology team.” He pointed one by one to the people on one side of the table. “Dr. Alice Bear. Dr. Greg Tungsten. Dr. Bob Shapiro. Dr. Saydi Obara. Dr. Evelyn Shar. And Dr. Izzy Rubka.”

Vars had heard of some of these people by reputation, of course, but never met any of them personally. EPSA people were a reclusive bunch, tending to mix with their own to the exclusion of others, even with the same research interests. It was one of the reasons Vars always wanted to join the organization–to get access to the best and the brightest minds and a chance to discuss the origins of life over coffee… But the introductions were happening so fast, there was no chance that she would remember how any of these names linked up with faces. Vars doubted she would even recognize these people walking down the street.

But Ian just continued. “And this group,” he gestured to two men and a woman, “is on loan from JPL–Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena. Trish Cars, Dr. Ron Silverman, and Dr. Benjamin Kouta.” Vars gave up on remembering who was who. “And these two,” Ian said, nodding to a pair of identical twins sitting next to him, “are Ibe and Ebi Zimov, our computer science wunderkinds from EISS, European Institute of Space Science.”

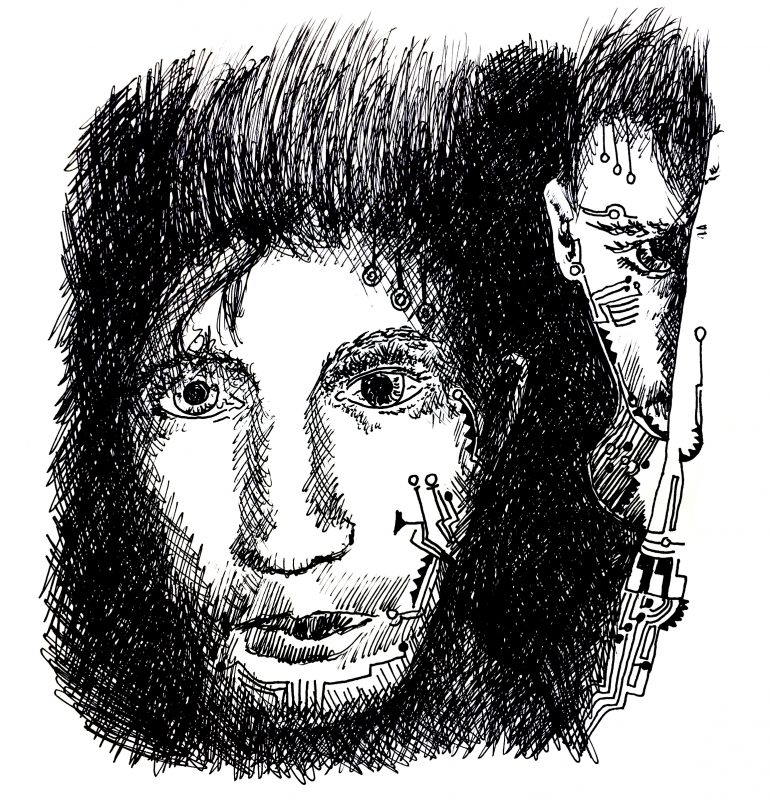

Ian pronounced their names as eye-bee and ee-bee; it was the only introduction Vars was likely to remember fully, as the siblings were the most interesting looking pair in the room. They seemed young–Vars guessed not older than twenty–and she was honestly uncertain whether they were male or female or one of each. They were dressed the same–sweatshirts with the EISS logo embroidered on the left, black jeans, black canvas shoes–and both had their hair dyed jet black, shaved on the sides and long on top, falling over their eyes. Vars could see impressive sets of D-tats on the exposed parts of their necks and jaws and peeking out of the twins’ sleeves. Other people around the room presumably had D-tats too, but nothing so obviously ostentatious as these two.

“And before you ask,” Ian said, “yes, they are related to Dr. Sergey Aphanasievich Zimov.”

That name sounded vaguely familiar, but Vars had no idea who Dr. Zimov was.

She also noted that the other two people present–two men in military uniforms–were not introduced.

“It’s a pleasure to meet you all,” she said. “Please call me Vars.” She smiled at everyone, then turned to Ian. “But once again… Please, I’d very much like to know why I’m here.”

“I was just getting to that.”

She noticed that he looked tired, too. He hadn’t slept much on the plane either. Then again, pretty much everyone in the room looked haggard. Deep circles under the eyes were the norm, not the exception.

Before Ian could continue, one of the women from the exobiology team spoke up. “In your book, Dr. Volhard, you mentioned an example of how robots developed by collectivist cultures would be less likely to kill. Would you mind elaborating on that?”

Vars didn’t know what she expected–but it wasn’t this. “You flew me out here before dawn to talk about killer robots?”

The discussion of robots in her book was just an illustrative example, and a frivolous one at that. It was just a funny way of explaining the differences in value systems between collectivist and individualist cultures. She’d almost cut it from the final draft, but David Gatewood, her editor, had insisted she keep it in.

“Of course not,” Ian said. “Robots are just a small part of it. But if you don’t mind answering Alice’s question…” He gave Vars a pleading look.

“You’re serious?” Vars still couldn’t believe it. She’d worked four years on the book, and what had caught EPSA’s interest was a stupid joke. I guess David was right, she thought. People, even smart people, grab on to the most flamboyant metaphors.

“Should I explain the differences between collectivist and individualist societies first?” Vars asked. She looked around the room; she didn’t want to assume what these people knew, but at the same time, talking down to the top minds of the Earth Planetary Space Agency was completely unacceptable.

“If you don’t mind,” Ian said. He composed himself as if awaiting a lecture. In fact, every face in the room had that look of composed concentration that Vars was used to seeing in her grad students.

“Okay.” There was nothing to do but move forward. She launched into her introductory lecture on socio-evolution. “While there are many ways of classifying the various human cultures that arose in the last fifty thousand years or so, one division that can be made is focused on the perception of the role of an individual within the group. In collectivist cultures, the group needs are judged above the needs of an individual; in the individualist cultures, it’s the opposite, naturally.”

“Naturally,” echoed an older, tiny, dark-skinned woman with bottle-thick glasses and tightly cropped hair, the one who asked the original question. Alice something. Vars wasn’t familiar with the woman’s work. And she hadn’t encountered too many people, other than herself…and well, Ian, who wore glasses. In his case, Vars was almost certain it was all about self-image. She wouldn’t have been surprised if they were simple tinted glass. But Alice’s glasses were thick corrective lenses and far from attractive. Most everyone had their vision corrected in this day and age. So either Alice had a strange affectation or an aversion to treatment. Or perhaps she had a defect that couldn’t easily be fixed, which was rare.

“Logic clearly dictates that the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few,” said one of the youngish-looking men from the JPL team. Vars knew enough popular culture to know he was quoting a character from an old space-exploration series. Star Trek?

This is too basic, she thought, and she raised her discourse up a notch. “Let’s just jump right into the robot anecdote. Robots designed by collectivist cultures would be less likely to kill. They would have a stronger focus on the theory of mind, understanding and taking perspectives of others–”

“Can you backtrack a bit?” Ian asked.

“Sure.” Vars thought she now understood the Goldilocks zone she was to lecture to. “Consider guilt. Guilt is one of the strongest human psyche compulsions. We use guilt and embarrassment as tools for social compliance all the time. Guilt is motivational, so to speak. Our social media landscape is full of guilt traps. We finger people who don’t pay taxes or contribute in a positive way to our society. We name people who don’t recycle or who drop trash on the road or who still use personal transportation vehicles. We social-shame not only the anti-social behavior but even the way people dress and look.”

A man in the back spoke up. “We are all familiar with cyber bullying, Dr. Volhard. EPSA is a large, multicultural organization, and we’re all required to take classes and workshops in antisocial behavior and sensitivity training.”

“I do too, as a university professor and researcher,” Vars assured them. “But my point is that social shaming works.”

“On robots?”

“I’m getting there,” Vars said with a smile. “People from collectivist and individualist societies experience guilt differently. A person from a collectivist culture feels guilt as ‘What will people think of me?’ While someone from an individualist culture perceives it as ‘How will I live with myself?’ See the difference?”

“So outcomes vary?” Ian asked.

“Precisely! Consider a criminal,” Vars said. “A person who commits a crime in an individualist culture can’t escape guilt, for the feelings of guilt are experienced internally, whether anyone is aware of the crime or not.”

“Are you implying that in collectivist cultures, a criminal won’t experience guilt the same way?” Alice asked.

“That’s precisely it, Alice.” Vars made herself say the name of the woman to reinforce it in her memory–a simple mnemonic trick. “It’s easier to commit a crime if you’re convinced that no one will learn of it and you live in a world where it’s only the opinion of your group that matters.”

“So a murderer won’t lose sleep over his deed if he was raised in a collectivist culture?”

“I’m saying that the guilt is assessed differently,” Vars said. “And it’s always about the extremes of the spectrum: the extreme form of collectivism, the extreme form of individualism. Of course, we live in a world that is both a little collectivist and a little individualist. I’m giving you the very antipodes to make my point clearer.”

“Of course, Dr. Volhard,” said Ian. “So the robots?”

“Yes, the robots. I’m getting to that, but first one more point.” Vars took a big gulp of coffee. It was cold and bitter now, but she needed the caffeine.

She must have made a face, for Ian was instantly on his feet, getting her a refill in a fresh cup. She waited for him to sit back down.

“Thank you, Ian,” she said, taking a sip. “Much better.”

“My pleasure.”

“And this is a perfect example of my next point: the theory of mind. Ian saw my expression when I took a sip from my cold cup and guessed that I was dissatisfied with my coffee.”

“It was obvious,” Ian said.

“To you.”

“I think it was obvious to everyone in the room,” he said with a smile.

A few people chuckled.

“That bad? Well, good. Then everyone here has a good theory of mind. You were all able to interpret my feelings, thoughts, and experiences even though you had no direct access to my taste buds. The theory of mind is necessary for higher-order thinking skills. It’s necessary for communication, for understanding multiple points of view. Not all animals on Earth have this ability, and even human children take several years to master this skill. Before the age of about four, kids are unable to switch perspectives and understand what motivates others. And even after that age, the theory of mind continues to develop into and throughout adulthood.”

“The development of empathy,” Alice said.

“That too. Empathy requires that we try to put ourselves in another’s situation to understand how they might feel. This is different from sympathy, obviously, which doesn’t require such cognitive acrobatics. So a child of five would flinch and hold their hand after observing someone get hit on the hand. It’s almost like the pain of another is their pain.”

“Are you saying that there’s a difference in the development of the theory of mind between collectivist and individualist cultures?” Ian asked. He’d clearly read her book and was now helping his team to quickly get up to speed on the subject.

“Yes. In a collectivist culture, the theory of mind is paramount. The focus of collectivists is on others, so the success of the culture is dependent on nuanced social interactions that require complex cognitive activity and deep understanding of the feelings and motivations of others. In individualist societies, the focus is on the self, so the theory of mind is of less central importance.”

“Thus robots designed by collectivist cultures would be less likely to kill,” Ian said.

There were murmurs among the people around the table. Apparently not everyone was buying the conclusion about the robots.

“Didn’t you just say that in a collectivist society it is easier to commit a crime?” Alice asked.

“Not easier, but with less guilt–and, even then, only so long as the crime isn’t discovered by others in your group. In a collectivist society, as long as the crime remains hidden from the group, there are no ill consequences to the individual. But note that committing a murder requires a deep understanding of what others know, how they will react to the crime, and how they will feel about the perpetrator. One would need a deep understanding of the entire web of social interactions.” Vars paused. “Again, I’m talking about extremes. But it stands to reason that robots created by collectivist societies would be designed with a focus on the theory of mind, with the ability to analyze problems from multiple perspectives. And such social cognitive flexibility puts more restraints on antisocial behavior than guilt alone.”

“So the robots we design are more violent?” Alice asked.

The “we” came up a lot in Vars’s classes. Everyone assumed that Western cultures were the most individualistic.

“Only if we design them so,” Vars said. “But most of this is discussed in my book, and you clearly all have access to my work…” She trailed off meaningfully. All of this was in her book. It didn’t make sense to her to be dragged urgently across the country for this predawn meeting. What did EPSA really want from her?

“Ibe,” said Ian. “Could you run the short version of our presentation for Dr. Volhard, please?” He turned to Vars. “It’s really the best introduction to our problem, and we can fill you in on details after.”

The way he said “problem” made Vars uncomfortable.

Ibe and Ebi both got up and set up the presentation. One of them pulled up the oversized sleeve of his black sweatshirt and exposed an ostentatious set of D-tats on his right arm. That twin was a lefty, Vars noted, and a body-computing junky. She’d bet there was another, equally extravagant set of D-tats on the other arm.

She glanced around the room and noted a few other PCD tattoos peeking from people’s clothing. Vars heard that EPSA was heavily invested in cyberhumatics–the science of human implant technology and its connectivity with global networks and robotic extensions–so it wasn’t surprising that D-tats were the norm among this group. But Vars had no implants, and it made her feel even more of an outsider.

Dark shades descended over the wraparound windows, cutting off the rays of the morning sun. The lights turned off, and the room was swallowed in a soft purple gloom. Vars yawned into the darkness–it would be so easy just to fall asleep in here, even with an almost full cup of coffee in hand. She heard others yawn as well. Yawning, she knew, was contagious among primates and other empathetic animals.

A 3D projection of the solar system lit up in the center of the conference table. The planets slowly rotated in their orbits. It was a very nice model, but of course it would be–this was EPSA.

“This is our solar system,” Ebi said. Her voice pegged her as a girl.

Ibe spoke next. “This is Saturn. And this is Mimas.” Based on the timbre of his voice, Vars judged him male. So not identical twins.

Using a combination of hand gestures and rapid tapping on his D-tats, Ibe zoomed in on Mimas, Saturn’s closest moon. One side of the small whitish moon had a giant crater with a dimple in the center. “Mimas is primarily made of water-ice. As you can see, it’s heavily cratered. The big one is named Herschel and is nearly a third of the moon’s diameter.”

“That’s almost eighty miles wide and over six miles deep,” Ebi added. “That pimple thing in the center is a mountain that’s almost four miles high.”

“That must have been some impact,” said Vars. Based on the initial questioning, this was not how she’d thought the rest of the morning would go.

“It liquefied the little moon,” Ibe said.

Most of the Saturn moons were well explored, and EPSA was actively working on establishing permanent science stations on some of them. But as far as Vars knew, none of the moons of either Jupiter or Saturn harbored anything more complex than simple bacterial life. Impressive, certainly, but old news now. And not something that an evolutionary socio-historian could help with. Vars’s specialty was the development of self-aware cultures.

“A year ago, we detected a signal coming from Mimas,” Ian said.

Ibe zoomed in on the giant crater and focused the image on the mountain. The rotation stopped, and the holographic image froze on a close-up. Vars could clearly see something protruding from the ice–a small, dark structure near the base of the central mountain.

Vars inhaled. She was no longer sleepy; all tiredness had been wiped clean. “What’s that? One of ours?”

“No,” said Ebi and Ibe in unison.

“And that’s the main problem of the day,” Ian said.

“You mean you don’t know?” Vars asked. “It’s been what? Twelve–”

“We have been able to divert one of our probes, and it arrived on site a few weeks ago,” said of the men from the JPL team. Ben?

“So this picture…” Vars said.

“Yes, it’s from that probe,” said Ben. “We have detailed close-ups.”

Ibe zoomed in even further, until the structure occupied most of the conference table.

“Wow,” Vars whispered.