There is always another solution…

Chapter One: The County Fair

I always loved my Uncle Charlie the best. He never looked down on me, even when I was still stuck in my wheelchair. He always listened carefully and never jumped to conclusions about what was “really good for me.” And most importantly, Uncle Charlie loved me. He was everything an eight-year-old boy could ever want from an adult. Except that he lived very far away. But every fall, he would drive up to our house in his gleaming red convertible, with presents in the back for my baby sister and me and my mom, and stay for a few glorious days. Despite all that Christmas offered, the abundance of Thanksgiving, the nighttime fun of Halloween, and the rockets’ red glare of the 4th of July, what I loved and looked forward to the most were those days when Uncle Charlie stayed with us. I waited for him to come all year.

I was a poor invalid boy all year except when Uncle Charlie looked at me. Then I was as healthy as any other kid my age. It didn’t matter that I couldn’t run, couldn’t walk, really. Uncle Charlie saw me as an interesting and smart human on his way to adulthood. No one else saw me that way. What I loved most about him was how I saw myself when I looked in the mirror during those few days when he stayed with us. I learned to nourish that image for as long as possible, for I knew it would fade long before Uncle Charlie returned for his next visit.

The year I turned eight, Uncle Charlie came as usual, just days before my birthday. It so happened that year that the county fair coincided with his visit and my birthday. That had never happened before, and I think I went out of my mind with the anticipation of all the fun we would have when he arrived.

I remember that visit as if it was yesterday. Nearly a dozen years didn’t erase a single detail, I believe. Uncle Charlie arrived later in the day than usual. Mom insisted that I go to bed. And as much as I protested, I ended up tucked under the covers, my crutches on the floor by my bed, staring out of the window, hoping not to accidentally drift off to sleep before I heard the telltale sound of wheels on our gravel driveway.

I lay in bed and listened through the floor as my parents argued in the kitchen. Back then, I didn’t understand what they fought about. I bet most kids don’t really understand their parents’ arguments; they just feel the unhappiness in the air like a foul-smelling blanket. And since I didn’t know any better, I just assumed all adults argued. All except Uncle Charlie. I’d never heard him say a cross word for as long as I could remember…back then.

***

I never managed to stay up late enough to hear Uncle Charlie arrive, but he was there to greet me in the morning.

“Hey, Hig. Rise and shine!” He called me Hig for the atomic symbol for mercury: Hg. You might ask why? Well, my real name is Fred, like my father’s and grandfather’s, and everyone called me Freddie…except Uncle Charlie. He gave me a nickname taken from his favorite rock band of all time: Queen. The lead singer was this dude named Freddie Mercury. So Hig, get it? It was our secret. Why I have that nickname is still our secret even now…mostly, although more people know me as Hig. The name Freddie got lost in histories.

“Uncle Charlie!” I threw my arms around his slender shoulders, and he lifted me gently out of bed. I was never embarrassed when he helped. He was so genuine and matter-of-fact about it all that it never felt wrong. When my dad tried to help, on the other hand, it always left both of us feeling awkward.

“We have to be quick,” he said. “Your dad said that he would take the whole family to the county fair if we can get our act together fast. I volunteered you and me for breakfast duty!” That’s how my uncle was; he didn’t say he was here to help me get out of bed and wash up and get dressed. Instead, he talked about “us” cooking breakfast for the family! “Your mom is helping Nonaken,” he added as he got me dressed. Nona was only a year and a few months old. Uncle Charlie added a diminutive to her name because he thought Nona was just too formal a name for a baby; Nona was named after Dad’s grandmother. Nonaken stuck—even Dad called my sister that…perhaps because he used to call his grandmother Nona. Awkward.

I tried to be as helpful as my body would allow. My arms had grown stronger in the past year, so I was able to stand on crutches for a few minutes at time. The doctor said it was important for me to do so. But my legs were useless. They kept getting in the way of things. I once asked my mom to have them cut off, but she just cried. Well, they turned out to be useful in the end. Mom was right.

Uncle Charlie looked frail, but he was incredibly strong. He worked as a nurse in a children’s hospital. I always thought those kids were lucky to have him. I wished I had him for more than just a few days a year. So he got me ready in no time and carried me down to the kitchen. Once I was settled into my wheelchair, he quickly organized eggs and bacon and toast. By the time my dad showed up, the whole kitchen smelled great.

“I can only go for a few hours,” Dad said. “I have to return to the office.”

“But it’s the weekend!” I still remember how whiny my voice sounded. I immediately felt embarrassed in front of Uncle Charlie. “Sorry, Dad. A few hours would be amazing.”

My dad grunted something in return and settled at the table to read the paper on his phone. Uncle Charlie winked at me and continued to juggle pots and pans to work a breakfast miracle. When Mom and Nonaken came down a few minutes later, all was ready. It was a great meal. I almost never got eggs with bacon and toast unless Uncle Charlie was in town.

“It looks amazing, Charlie,” Mom said and got my sister strapped into a highchair.

“Freddie and I tried,” he said, beaming back. All I did was set the table…badly. But I was happy to share in the praise. It was so rarely bestowed in my direction.

My mom was Uncle Charlie’s older sister. I think there was just a two-year difference between them, but it felt much more to me. Uncle Charlie was fun and playful and silly, while my mom was the exact opposite. Dad just said that was because Uncle Charlie lacked seriousness of character. But I think it had more to do with the fact that he was still a child at heart. At least I felt that we were equal somehow.

When Dad finished with his coffee, the kitchen table was cleaned, the dishes washed and put away, and we were all dressed and ready to go. No one wanted to give Dad an excuse not to go to the fair.

My dad was dressed in a suit and tie; he planned to take Uncle Charlie’s car to the office directly from the fair. We were taking two cars so we could spend a bit more time exploring the animals, and food, and the crafts pavilions. In retrospect, my dad probably agreed to go to the fair so he could take that red convertible to the office. But I was none the wiser back then, and we needed the minivan for my wheelchair, Nonaken’s stroller, and stuff. So, logistically, it probably did make sense. Still, I was just so happy to be going at all. If Uncle Charlie came a week later or a week earlier, we wouldn’t have been going to the fair at all. Mom couldn’t manage with Nonaken in a stroller and me in a wheelchair by herself. It was too much for her.

“Sissy.” Uncle Charlie always called Mom “Sissy,” short for sister, I guessed. “Why don’t you put on that orange jacket I sent you? The one with all the wild flowers.” The jacket was orange because it was covered with California puppies.

“It’s not really practical, Charlie,” she said, slipping into her frumpy gray sweatshirt. “What if I spill something on it? I can’t even dump it into a washer. I’ll save it for sometime special.”

“So you will wear it sometime? You like it?” he asked, just like a kid.

“You know I do, Charlie,” she said with a sad smile. My mom’s smiles were always sad.

“Okay. But it better be soon. You look at least ten years older than you really are in that,” Uncle Charlie said. He was wearing jeans and a colorful Hawaiian shirt that looked oddly feminine to my eye. “You know, I can babysit tonight, and you and Fred can go–”

“I’ve told that I have to work late tonight,” my dad said. I didn’t even realize he was paying attention. “I’ve agreed to this silly outing, it will have to be enough.”

I was going to argue, but Mom gave me that look, and I didn’t say a word. We all piled into our minivan: Mom, Uncle Charlie, Nonaken, and I. Dad took Uncle Charlie’s car. Thirty minutes later, we were pulling out the wheelchair and the stroller and a giant bag with extra diapers and food for Nonaken and other private things for me. Because of my disability, we could park right by the entrance to the fair, in the special blue zone. Dad waved us to go ahead as he looked for parking next to the exit. We already purchased the tickets and were getting ready to go in when Dad finally joined us. He missed all of the hassle and the ticket line and everything. Uncle Charlie just called him lucky. Mom already looked pooped. She got tired fast, I noticed.

***

The fair was everything a kid dreamed it would be. There were farm animal competitions and even a small arena where kids could get a ride on a pony or in a goat cart. There was a humongous food court where restaurants and farms from all around our area set up booths and food trucks. Anything a kid would love: two-foot corn dogs, watermelon-sized spun sugar in rainbow color assortments, deep-fried Twinkies served in a tub of melted chocolate, any flavor of shaved ice by the bucket, fried chicken and BBQ ribs dripping with rich sweet sauce, roasted brown and crisp turkey legs, and a vast assortment of homemade stuff coming in a million combinations of sweet, sour, piquant, salty, pungent, and oleogustus. The last flavor was taught to me by Uncle Charlie. It meant the degree of fattiness. And boy oh boy was oleogustus well represented at the fair. There were also miles and miles of pies filled with so many combinations of fruits, berries, and even vegetables that there was no point in even trying to keep track. I really never understood how all those pie judges at the fair managed to do their job, but it was fun to imagine–When I grow up, I will be a pie judge at a county fair. It made me smile.

The fair also had a ton of amusement park rides, the kinds that spin and throw you around and even twist you upside-down. But I was never allowed to go on those, of course. And Nonaken was too young. She squealed with delight when Uncle Charlie simply rocked her stroller a bit too enthusiastically. She was easy to please. My dad was less so.

We tried to go see the chicken competition; the prettiest and smartest chickens were being shown off in one of the pavilions. But my dad said he couldn’t go anywhere where there was hay or wood chips on the floor—it was bad for his shoes. So we went to one of the crafts pavilions. Some of my mom’s friends had quilts in a competition, and she wanted to show her support. The place was huge, and we wandered around looking at cool things people made all year long to bring to the fair. There were cut crystals and homemade soaps in shape of crystals. Tons of honey in every shade of amber. Toys. More toys. Clothing and more clothing. One booth had nothing but hats. Uncle Charlie managed to surreptitiously buy a huge wide-brimmed hat with a whole bouquet of silk flowers pinned to the top for my mom. She refused to put it on, so Uncle Charlie wore it instead. It made Mom and me laugh. Frankly, I thought it looked good on him. Dad just frowned and walked ahead, pretending he didn’t know us.

There is a smell and sound to the county fair. It’s instantly recognizable to all those who’ve ever attended one, even once in their lives. We were soaking in the aromas and drowning in the sounds of the fair. It was more fun than anything I could remember since the last time Uncle Charlie came to visit and took me fishing. We didn’t catch a thing, but it was still a load of fun. We even brought home some fish…that we bought off one of the fishermen. We tried to pass it off as our catch, but neither Dad nor Mom believed our fish story. It made for a good dinner either way.

“I bet even Nonaken will remember this,” I said about the fair.

“She is too young, Freddie,” Mom said, but she too looked a bit drunk on the fair’s smorgasbord of sounds, colors, and smells.

“Oh, Nonaken will definitely remember,” Uncle Charlie assured me. “She might not get all of the details–”

Mom laughed. My sister was snoring in her stroller, despite the din of laughter and the endless clamor of the place. “Nonaken is totally tuckered out, Charlie. We will be lucky if she doesn’t throw a tantrum when we get home.”

“Well, I did say all of this is just too much a little kid,” my dad said. “You will just have to manage her overexcitement without me tonight.”

“Don’t worry, Fred,” Uncle Charlie said. “We’ll manage.”

“You’ll have to. I have to work hard to feed this family, Charles. You don’t have the responsibilities of taking care of a wife and children. Life is simpler for you. I have to work all the time to help us manage.”

I noticed the tension between Mom, Dad, and Uncle Charlie even back then. Dad always talked about the importance of being professionally successful. He said that he felt the pressure to get ahead more keenly because of me. He said that he would probably have to take care of me for the rest of his life. I hated that. I was sure that when I grew up, I would be able to manage on my own. Uncle Charlie told me lots of kids with spina bifida grew up to hold important jobs and live independently. He told me that Franklin D. Roosevelt, the president of the United States, was in a wheelchair when he did his job of running our nation. No one needed to support President Roosevelt all his life. So, sure, I might need more help with day-to-day stuff than most people. But we all need help from time to time, Uncle Charlie said. I believed him.

As we started to make our way toward the crafts pavilion exit–Dad was trying to rush us out–we noticed a small booth run by a blind woman. You might ask how I knew she was blind. Well, her booth sign said she was, and she was wearing very dark sunglasses and used one of those long white canes with red stripes. Uncle Charlie stopped to see what she was selling. Since he was the one pushing my wheelchair, I stopped too. And my mom, with Nonaken sleeping in a stroller, paused to see what was going on. Dad almost walked out without us but turned back when Mom called him.

“Let’s do it, Fred,” she said. “Let’s all go do it. It will be fun!”

“I second that,” said Uncle Charlie.

“I third it!” I cried out. It was a Fun House Mirror Booth…with just one mirror! The sign above read, “Take The Test.” Just that, no other instructions or explanations.

“It’s just one mirror, Fred. It won’t take long,” Mom begged, and Dad grumped but agreed.

That’s how we all ended up doing the “Mirror Test.”

“You have to go one by one,” the blind woman told us as she took off her glasses. Her eyes were a scary milky-white color all over, no iris, no pupils, nothing at all. “This young man,” she pointed to me, “will need to use his crutches. Can you walk this far?” She spread her arms as wide as they could go to indicate the distance.

“Of course I can!” My crutches were strapped to the back of the wheelchair. It was easier to use crutches sometimes…like for the bathroom and stuff.

“Very good, young man,” she said. “I would like the pretty man with a hat to go first.”

I laughed. Of course she meant Uncle Charlie. He and Dad were both wearing hats, but Uncle Charlie was the only “pretty” man in our group. Honestly, I’d always thought of him as pretty rather than handsome. He had big blue eyes and gently curling blond hair that framed his thin, delicately featured face. He looked a lot like my mother, except years younger. I overheard Dad say once that Uncle Charlie would have made a prettier woman than my mother. He was wrong, of course.

Uncle Charlie took off the giant hat and walked behind the curtain that contained the one mirror. We all waited outside. It seemed to take a very long time. Nonaken even woke up and was looking at all the colorful spinning and whirling wheels and thingies all around us–the garden sculptures that were designed to keep the birds off the fruiting trees sold in the booth next to the Fun House. The only bits of darkness among the exuberant explosion of colors were my dad’s suit and the curtain that hid the blind woman’s mirror.

When Uncle Charlie stepped out, we all turned on him.

“How was it?” Mom and I asked almost simultaneously. He just shook his head and lifted Nonaken from her seat. She wanted to touch a rainbow ribbon floating above our heads.

“Well,” Dad said, looking at his watch. “I really need to go back to the office. So if you’d excuse–”

“It’s your turn, Mr. Keen,” the blind woman said. I don’t know how she learned our last name, but it had an effect on Dad. He shrugged, went inside, and disappeared behind the curtain.

Dad took even longer than Uncle Charlie. At least it felt way longer. Nonaken was starting to get crotchety and was on the verge of tears. Mom took her in her arms from Uncle Charlie, who seemed unusually quiet for some reason. Finally, the curtain pulled aside and Dad stepped out. He gave the blind woman a ten-dollar bill and, without saying so much as goodbye to us, left. I just watched him go. It was an unexpected departure, even for my dad. He always at least kissed my mom’s hair before rushing out to go to work.

“Well, it’s your turn, Mrs. Keen.” The blind woman smiled at my mother. I noticed she had a bunch of gold teeth in the back of her mouth. I wondered if she knew about those, being blind and all. “Don’t worry about the baby. She is too young to understand, and so it won’t mean nothing to her,” the woman added.

Mom nodded and walked in, carrying Nonaken. She came out almost immediately. I saw a tear running down her face. I wanted to ask if she was okay, but I was being hustled onto my crutches and into the booth. And then I was the one facing the mirror.

As soon as the black curtain fell closed behind me, all sounds and smells of the fair disappeared. That should have been my first clue that this was something out of the ordinary. But at the time, I was too overwhelmed to pay attention to those kinds of details. I was looking at a young man in the mirror. He was me and not me. I have to say that I generally didn’t like to look at myself in the mirror. Who in my situation would? But the reflection looking back at me was more like the image of myself I had in my head: healthy, strong, able-bodied, not sickly at all. I was looking at an athlete, at someone who could jump over a fence or climb a tree without even thinking about it, at someone who could run to school every day and never ever get tired, at a boy who was confident and vigorous. The kid who smiled at me from the mirror would be chosen by other students to be on their teams first. So not like me. So me… I felt tears rolling down my face. I wanted more than anything to be that kid in the mirror. I almost hated the blind woman for showing this to me. I understood why my mom shed a tear–she probably saw something equally improbable when it was her turn.

I had to make myself look away. It was almost painful. I wanted that mirror to reflect reality so much. I closed my eyes and turned away. It was easier to turn once I couldn’t see the evil reflection. I pushed the curtain and stepped back out into the pandemonium of the county fair.

That was thirteen years ago.

But to understand what’s happening to me now, you need to know more about what happened after that day at the fair, all those years ago.

Chapter Two: After the Mirror Test

Once my dad left us alone at the fair, we wandered around, looking at the raucous chaos of food, toys, and entertainment still available for us to sample. We went to the chicken competition–Araucana won. Apparently that farm won every year, but it wasn’t my choice. Yes, I focused on the feathers and size and demeanor of chickens on display to try to push aside what I saw in the mirror. I think Mom and Uncle Charlie did the same. Uncle Charlie even placed a bet on a Padovana chick, but he didn’t even notice when the judging was over and he lost. Mom too seemed over-excited about random stuff and at the same time almost catatonic for minutes at a stretch. It scared me. What did they see in that mirror? What did my dad see? He left us at the fair and didn’t even say goodbye.

Finally stuffed with random food and totally exhausted from crisscrossing the fair dozens of times, we headed home, carefully avoiding coming anywhere near the blind woman’s mirror booth. Dad wasn’t home yet. In fact, he didn’t return until we all went to bed. We didn’t talk about it. And we didn’t talk about the mirror or the blind woman at all. It was as if that never happened.

But in my bed, with the lights out, I could see the face of that boy so clearly. And I longed with all my heart to be him. I fell asleep crying.

In the morning, when I woke up, I lay there listening to the house. My parents were arguing again. I didn’t want to know what it was about. Because regardless of what they said down there, it was about the mirror. Everything was about the mirror from that day forward.

Uncle Charlie left in the middle of the night, as soon as Dad returned with his car. I didn’t realize that until I finally tried to crawl out of bed–no one was coming to help me. I managed to sit up by pushing off the mattress and was able to get the crutch off the floor. It was almost easy. One crutch, then another I accomplished getting to the bathroom and voiding my bladder all by myself. For the first time in many years, I didn’t have an accident during the night. I should have been elated. You probably have no idea how it feels to be in a third grade and still needing a diaper. It’s humiliating. But I was clean.

I brushed my teeth and got dressed by myself–another personal achievement. I was on a roll. I used my butt to slide down the stairs–a familiar maneuver that also seemed easier today–and hobbled over to the kitchen door.

“Did you say something to Charlie to make him go?” Mom was crying; her hands shook as she tried to pour coffee for my dad. Dad just ignored her. But he always did that, so it wasn’t anything new. But Mom tended to do all her crying in the privacy of her bathroom, and Uncle Charlie never left without saying goodbye to me before.

“Uncle Charlie left?” I asked like an idiot. Of course, I figured that out already–his car was gone and the guest room door was ajar and bed stripped. What I really wanted to know was why he left.

“You made it down all by yourself?” Mom asked, ignoring my question. She rushed over to me with the wheelchair, and I collapsed into it. Getting down the stairs took everything out of me, but I forgot about it while grieving Uncle Charlie’s departure. “You shouldn’t have,” Mom said. “You could have fallen down the stairs. You could have…” She let out a sob and stopped.

“I’m okay, Mom. See?” I smiled at her from my chair. I wished Uncle Charlie were here to cook breakfast for everyone again. We needed him.

“Leave him alone, Moira,” Dad said. “A little independence is good for the kid.” And without saying another word, he left. The front door slammed, and we listened as he drove away. He didn’t kiss Mom’s hair goodbye. That was twice in a row.

***

The following several months were crazy. Mom cried all the time. Dad was gone from early in the morning to late at night. He stopped coming home for dinner. All those missed meals turned into weight loss that Dad proudly mentioned any time we actually got to see him. He said that he had started going to gym regularly, thus all the absence. He dressed better. He looked great–even I noticed. Mom, on the other hand, didn’t. She too lost weight, but on her it looked more like wasting than dieting. The word I learned from looking up Mom’s symptoms online was cachexia–unexplained weakness and weight loss. She had in spades. I tried talking to Dad about it, but he refused to pay attention to me. He said it was his me time now, and I should let him enjoy life a little; he deserved it. I was at a loss. I was only eight.

Personally, I was actually feeling better than I could ever remember. I was getting up, getting dressed, and getting myself downstairs by myself on regular basis now. Sure, there was a fall here and there that set things back a bit, but I was obviously better. Even my teachers at school noticed. I tried to get in touch with Uncle Charlie to tell him my good news and to ask him for help with Mom, because she didn’t want to listen to me either. She just nodded every time I brought up the fact that there might be something wrong with her and then just ignored me. I needed Uncle Charlie. He was the only one who could help–he was a nurse, after all–I was convinced. But I couldn’t get hold of him.

First, I tried sending him a few texts to his phone and via social media and such, but he never responded. Three months after the fair, his number stopped working all together. I knew the hospital he worked at in California, so I called their general number. Someone somewhere had to know what happened to my uncle. After multiple tries over several long weeks, I got hold of a night nurse on duty at the pediatric cancer ward, Nurse Megan.

“Is this Hig?” she asked after I introduced myself–apparently, she’d heard of me. Her voice was nice, clear as a bell. But I was surprised she knew my nickname, surprised Uncle Charlie would share something so intimate and private with a stranger. Of course, she was probably not a stranger to him. “Charlie told me that you might call, looking for him,” she said. She sounded kind. I met lots of pediatric nurses over the years, and I could recognize a good one just by hearing the voice.

“I really need to get hold of him,” I said. “It’s a family emergency,” I added, realizing that it was in fact that.

“He told me you would say that too,” she said.

“He did?”

“But you see, Hig, Charlie had to take some time off…for personal reasons. He told me to tell you that when the time was right, he would contact you himself. He asked you to be patient and not be too mad at him. Okay?”

“He said all that? But I really need him now. Really! I didn’t lie about the family emergency. You see, I think there is something wrong with my mom,” I told her. “I think it is serious.”

“Huh.”

“Uncle Charlie didn’t tell you about my mom getting sick, did he?”

“No, he did not. What’s wrong with your mom?”

“She lost a lot of weight. And before you say that’s a good thing, it isn’t. She was never fat. She was thin like Uncle Charlie. But now she’s sort of skeletal. I can see her bones. She hides it by wearing bulky clothing, but she is so thin, it’s scary.”

“Did you try talking to her about it?”

“Sure. But she won’t let me. She says everything is just fine. But it is not fine. She gets really tired too, now. I saw her needing to sit down on a couch. She looked like she was going to pass out. And she is having problems carrying Nonaken around.”

“That’s your baby sister?”

“Uncle Charlie told you about her, too?”

“I’ve seen photos. Nonaken, Little Nona.”

“That’s her! She’s the only one who is still normal.”

“What do you mean, Hig?”

“Well, Dad lost weight too, but he goes to the gym a lot and works out all the time. He got promoted at work and even bought a car like Uncle Charlie’s.”

“You mean that funny little red thing with no top?”

“Dad always thought it was cool. He used to borrow it from Uncle Charlie when he came to town. But that’s not what’s important. Something happened. Something happened at the fair.” There, I said it. I didn’t mean to. I wanted to discuss it all with Uncle Charlie, but he wasn’t around.

“The fair…” she started to say, but stopped.

“Yes. Did Uncle Charlie tell you about the fair? About the Mirror Test?” It felt good to say those words out loud. I didn’t dare before that day.

“He mentioned something about meeting an oracle at a county fair. He tried looking her up.”

“Did he find her? Did he find the blind woman?” I was so excited, I practically yelled into the telephone. I never thought of trying to find the woman with the mirror. Of course, she was the person who could give me answers. Of course! “Did he?” I asked again.

“No, Hig. Charlie tried. He drove back to look for her–”

“He came back and didn’t see us? Didn’t stay with us?”

“Charlie had work, Hig. He couldn’t–”

“But he didn’t stay the full seven days with us like he usually does.” I tried to argue, but it was silly. Uncle Charlie always stayed with us for as long as he could. But he frequently reminded me that there were dying kids waiting for him to return. He couldn’t abandon them. I understood…sort of. “He didn’t even call me…”

“I’m sorry, Hig. I’m sure he would have, if he could.”

“Did he ever find out more about the blind woman?”

“No. He called the organizers of the fair and described her and her booth, but no one seemed to know what he was talking about.”

“But that’s crazy! We were all there. We saw her.” Now I wished that we took some snapshots or something. But we were all so unsettled at the time, and Dad was…well, I wished I had some proof of that booth’s existence.

“I don’t doubt you…or Charlie,” she said. But it sounded like she did. “But Charlie never figured out how she got listed at the fair…or not listed. And the organizers said they’ve never heard of a one-mirror fun house booth. But he did look, Hig. Charlie was obsessed with trying to find this blind woman.”

“Huh. But nothing?”

“Not as far as I know,” Nurse Megan said. I could tell she would have told me if she knew anything else.

“Thanks anyway.”

“Wait, Hig,” she called into the phone. “Charlie promised to call me as soon as he could. We were best friends, you know.”

For some reason that got me super angry–I was family. If Uncle Charlie called anyone, it should be me. “Where did he say he went?” I asked as soon as I could control myself, swallowing a painful lump in my throat.

“I really don’t know, Hig. He didn’t tell me, honest. But…I think he is still looking for this blind woman. I saw him get a list of all the county fairs for the upcoming year. I think he was going to go from one fair to another in person, trying to find her. I don’t really understand what happened to you all,” she added.

“I don’t either,” I said.

“But something did happen, right?”

“Yeah. Something.” I thought of how handsome and successful my dad suddenly had become and how sick my mom looked…and how much better I was feeling. “Did you notice anything about Uncle Charlie before he left?” I asked. I never really considered it, but what did my uncle see in that mirror? Did he change somehow too? That blind woman said that Nonaken was too young, but the rest of us… “Did he change somehow?”

There was a long pause. I was even afraid that Nurse Megan hung up on me. But finally she said, “He got even prettier.”

“Yes.” I could see that.

“It was nice talking with you, Hig,” she said. She sounded sad. “I really have to get back to my patients. But you be good and take care of your mom. Get her to see a doctor. Maybe you can ask for yourself and then explain at the office your concerns for your mom.”

“It’s a good idea. Thanks. Goodbye.”

“Goodbye, Hig. And keep in touch. Just call this number from time to time.” And with that the line went dead.

I held the phone for a long time afterward. Telling my own doctor about Mom was a really good idea. I should have thought of it. I dropped the phone of the floor and threw myself down. It hurt a lot, but I heard my mom rushing up the stairs to see if I was all right. I was, but I insisted we go to the doctor, faking pain in my leg.

Chapter Three: The Mirror Miracles and Mares

“It’s been a while, Freddie.” Dr. Ulf shook my hand. He was huge, a perfect Viking. When I was little, I wanted to grow up to be just like Dr. Ulf–a doctor who specialized in pediatric birth defects and someone who looked like he could take over Greenland barehanded. My hand disappeared into his, and I grinned the silly grin of a groupie. Dr. Ulf always managed to make me feel good, even when I felt awful. “You’re looking great,” he said. “I see you’ve been working out.” He was feeling my upper arms, noticing improvements in my muscle mass. I was very proud of them.

“Freddie has been doing very well, Doctor,” Mom said. “He managed to walk all the way here on his crutches from the parking lot. No wheelchair.” That was the total of maybe one hundred steps, but still… Mom had Nonaken strapped into her stroller with multiple bags of supporting equipment for me and my sister. So it wasn’t like there was a way for her to deal with my wheelchair too. I was happy I could make it to the office under my own power, even after I threw myself onto the floor. “But he did just have a nasty fall,” Mom added.

Dr. Ulf was instantly on his knees, helping me with my sweatpants, looking at the damage. My leg did look bad. It was black and blue already. It would get worse before the day’s end. I knew how these things went; I had plenty of experience. I now wished that I had been more cautious. There was no real need to hurt myself to see Dr. Ulf. Mom would have taken me as soon as I complained of pain somewhere. But I was a perfectionist. And I didn’t want to lie…well, not more than I needed to.

“Looks like a bad fall,” Dr. Ulf said. “Did you get a chance to ice it?”

“No, Doctor. Freddie insisted we go straight to your office. And I was afraid…”

“No worries, Mrs. Keen. We’ll take care of your boy.” He helped me up on the exam table and pulled some ice packs from a little freezer under the sink.

“Ah,” I complained at the cold.

“Don’t protest, dear,” Mom was quick to intervene.

“I’m not. I’m just saying that it’s cold.” I rolled myself away a little. I did have far more upper body strength now. I’d bet I didn’t even need help to get down.

“I’m very impressed, my boy. You are showing remarkable improvements, despite the fall,” the doctor said.

“Freddie has been doing very well,” Mom confirmed again. “There have been a few falls in the last few months, but nothing as bad as this. And he has been managing everything himself, even getting down from his bedroom to the first floor.”

“Remarkable,” Dr. Ulf commented again. He was gently lifting up my shirt and examining my spine. His fingers were probing but gentle. Very much like Uncle Charlie’s.

“Dr. Ulf?”

“Yes, Freddie?”

“I have something private I would like to discuss with you.” I gave a sideways look at my mom. Mom started to protest, but Dr. Ulf managed to quickly escort her out into the waiting room. He was very good at managing things and people.

“What do you want to talk with me about, Freddie?” he asked and settled on a tall spinning stool across from the exam table.

I was still lying down, cold packs pressed into my body. I considered sitting up—I wanted to be more eye-to-eye—but I didn’t want to argue over my “treatment.” I had more important things to talk about.

“Dr. Ulf,” I said. “I didn’t really come here because of the fall.”

“No? It looks bad. It’s okay to–”

“No, I get it. Really. I will always call you if it is really important. I promise.”

“Good. So what’s this all about then?” Dr. Ulf was always straightforward like that. It was one of the things I liked best about him. He wouldn’t lie to me. If there was bad news, he would always tell me, not treat me like a stupid baby.

“I fell on purpose,” I said quickly, before I lost my courage. Dr. Ulf started to speak, but I stopped him. “It was the only way I could think of to get my mom into a doctor’s office. You see, my mom has been ill. Really ill. She lost a ton of weight, and she is tired all the time.”

“Hmm, I did notice that she looked more worn-out than usual.”

“She is. I saw her almost lose consciousness the other day.”

“Did you talk with her about it?”

“She won’t listen.”

“And your dad?”

I was bad. I rolled my eyes, indicating how little my father really cared about what was happening to us at home. But when Dr. Ulf sat and waited for me to give a real answer, I did. “I think my parents are having problems,” I said. “My dad hasn’t been around much. And he stopped kissing my mom goodbye.”

“I see,” Dr. Ulf said. “Do you think that your mom’s condition has something to do with that?”

I hadn’t considered that, but I was sure that was not it. “No. I think there’s something medically wrong with Mom. I’m sure there is. And since I couldn’t get her to see her own doctor…”

“You devised a way of getting her to see me.”

“Yes. I know it is wrong. But I really didn’t know what else to do. I’m very worried about her, Dr. Ulf.”

“Well, young man. Do you think you can babysit that little sister of yours while your mom and I talk in my office?”

“Would you?” I felt so relieved, I almost cried. “It’s no problem, Doctor. I babysit Nonaken all the time. It’s easy.”

A few minutes later, I was sitting on a floor of the exam room on a couch pillow from the waiting room with three cold packs strapped to my leg, while Nonaken sat in her stroller with a book she wanted me to read to her. Dr. Ulf and my mom were presumably discussing her health in his office.

A surprisingly short time later, Dr. Ulf and my mom returned. Mom looked like she planned on giving me a “talking to” when we got back home. But Dr. Ulf looked concerned.

“Well, I expect you back here in two weeks, Freddie,” he said. I swear he gave me a wink. “I would like to see how your leg is healing. Would that be alright, Mrs. Keen?”

“Of course.” But Mom didn’t look happy about it. Perhaps she suspected that Dr. Ulf had ulterior motives.

“And please, Mrs. Keen, I think your son would feel so much better if you took some time to take care of yourself. As you’ve said, Freddie has been getting stronger and stronger. He and Nona can clearly take care of each other for short periods of time–”

“We’ll see,” Mom cut him off. She really didn’t look pleased.

“Please, Mom?” I begged. “I told Dr. Ulf that I can’t get better if I worry about you.” Total lie, but I was sure Dr. Ulf would support me. “I can read to Nonaken in the waiting room while you see a doctor or something. It’s no problem, see?” I showed the book Nonaken picked out for me to read. It really was easy. My sister was an easy kid–as long as everything went her way, she didn’t protest at all. “You know I can take good care of Nonaken.”

“I believe he can, Mrs. Keen.” Dr. Ulf supported me.

We didn’t discuss what happened on the way home, or that night, or even that whole following week. I went to school as usual, Mom took care of Nonaken, Dad was absent through most of it…all of it, really. I gave my mom inquiring looks; she avoided me. She didn’t let me question her more. But she did seem grayer and grayer to me with each passing day. I couldn’t understand why no one else saw what I saw.

***

She collapsed while carrying Nonaken up the stairs. From my bedroom, I heard the banging as they both tumbled down and rushed out to help. It was just after dinner. We weren’t expecting Dad home for many more hours still. So it was just me.

I saw Nonaken lying at the bottom of the stairs on top of Mom, not moving. It was probably the fastest I’d ever gotten down the stairs. I felt panic in my armpits. Cold sweat was running down my back. My brain was humming loudly, making it impossible to think. Then Nonaken looked up at me and screamed. It was a tentative scream. I think she hadn’t figured out if she was hurt or not, but she was freaked. And so was I.

I dropped my crutches to the side and pulled Nonaken off my mom. My little sister’s blue eyes were as huge as saucers.

“Are you good, Nonaken?” I asked. She wasn’t talking talking yet, but Nonaken understood most things now. She nodded a bit and drooled on my lap. “Good girl,” I approved. I carefully palpated her arms and legs and back–I’ve learned from the best–she didn’t wince or anything, so nothing was obviously broken. “I’m going to put you down right here. And you be a very good girl, Nonaken, and don’t move. Okay?” She just nodded again. “Good girl,” I said and gently deposited her on the floor. She quickly turned over and sat up–she definitely seemed fine.

I turned to my mom. She was unconscious, not a good sign. I knew enough about not moving her–a spinal injury could get worse if the person was moved. I had plenty of experience with that. So I crawled all around my mom’s body, looking for signs of damage. I didn’t see anything obvious like blood, and her body wasn’t at any obviously bad angles. It didn’t mean that nothing was broken, but it was a good sign.

“Mom? Mom? Can you hear me?” I called to her. I leaned over and gently pulled up one of her eyelids. Her eyeball was still there. I had no idea what I was expecting, but I saw people do that in some movie or something. “Mom?” I called to her again. I bent over and listened to make sure she was breathing. She was. I felt her pulse and couldn’t find it. But she was breathing, so it was just my awkwardness. “Okay, Mom. I’m going to call an ambulance, all right? And I will call Dad too. I really don’t know what else to do. But if you don’t want me to do that, you have to tell me now. Like right now. Mom? ‘kay, I’m calling…”

I crawled over to my mom’s phone, which was lying a few feet away. It must have fallen out of her pocket during the accident. The screen was locked. It was one of those that recognized the face of the user to unlock its function. I put the phone to Mom’s face, but it didn’t work. Did the phone know she was unconscious?

“Okay, okay, okay.” I looked around. My phone was up in my bedroom. “Nonaken? Be a good girl and watch over Mom. I will be right back. I just have to go get my phone. Okay? Can you do that for me, Nonaken?”

My sister looked at me with those huge eyes of hers and nodded. She did understand. Good. I turned back toward the stairs and started to crawl up as fast as I could. I didn’t bother with crutches–it was easier to just crawl, if not more dignified. But who cared? Still, it took me a while to get up there. My hands shook, and I could feel adrenaline flowing through me, making everything more hazardous. But I couldn’t make a mistake and take a tumble. I had to be careful. My mom and Nonaken depended on me.

It felt like forever, but I was up in my room dialing 911.

“Operator? We need help. My mom fell down the stairs, and she is not moving.” I knew I sounded like a very little kid. I was scared, and that always raised the pitch of my voice. But the emergency operator woman believed me, and I managed to answer all the rest of her questions just fine. I knew our address, and I had memorized my dad’s phone number, so she called him for me, keeping me on the other line. I had to explain to her that Nonaken was just a baby and that I needed crutches to move around, so it would take me time to get back down to Mom. She waited patiently as I held the phone in my mouth and descended.

Mom was still nonresponsive. Nonaken was sitting next to her, holding her hand, and crying. I felt bad for her.

“It’s going to be okay, Nonaken. Help is coming,” I said as soon as I got down and took the phone out of my mouth. It was covered in my spit. Still worked, though.

The nice emergency operator told me that a police car and an ambulance were on the way. I had to get to the door and open the locks, but if I couldn’t do that, I shouldn’t worry–they would just break the door down. I knew Dad would freak at that, so I left the emergency operator to talk to Nonaken and got up on my crutches and made it for the front door. I got there almost at the same time as the cops.

From then on, it was a blur. One cop was assigned to talk to me. He helped me to the couch and brought Nonaken for me to hold. She screamed if anyone else tried to do that. She clung to me for dear life, poor thing. The ambulance people were all over my mom, loading her onto a gurney and wheeling her out of the house. When I explained that Nonaken also took a fall, they came back for her too and took me along with them. We left together for the hospital. I hoped someone locked the front door.

***

Mom was admitted. Nonaken seemed okay besides a scare and a small bruise on her shoulder, but the hospital kept her “for observation” overnight anyway. My sister was too young to really say if something hurt, and frankly, they couldn’t just release a baby into the custody of an eight-year-old, could they? So I was in the room with Nonaken, who finally fell asleep around midnight. I had no idea about Mom–I asked, but the nurses told me that they would get back to me later and that I should take a nap on a cot they wheeled into Nonaken’s room. I haven’t heard from Dad. But I also managed to lose my phone in all of the hassle and shuffle. I hoped it was just back home somewhere; Dad would go ballistic if I lost it lost it. It was very expensive, and I only got it because I was a crippopotamus–not being able to walk did sometimes get one a cool phone, but I wouldn’t recommend it. There really were very few benefits to having a congenital birth defect. I should know.

I woke up because Nonaken was crying. Light was already streaming through the window, so it was morning…but very early. I got out from under the blanket that someone must have put on me in the middle of the night and hobbled over to my sister. Out of consideration, someone had moved my crutches over to the corner of the room, neatly out of the way. I wished people were a bit less considerate and left them where I could reach them. Surprisingly, I hardly needed to grab at things on the way to the crib. I usually made fun of myself for “brachiating” across rooms and such, but my legs supported me just fine the four feet of open space I needed to cross over to get to my sister.

“What’s up, Nonaken?” I asked and sat on a stool next to her hospital crib. “Hungry? Wet?” I realized that we didn’t bring a diaper bag with us. So not only I had nothing for Nonaken, but I didn’t use anything myself overnight. Yet I knew I didn’t have an accident. I was so relieved and surprised that I almost cried, too.

“How are you guys doing?” A nurse walked in on us at that moment. Somehow, all nurses everywhere have developed a supernatural ability to sense pain and discomfort. I guess it’s their superpower.

“Fine?” I answered. My voice squeaked, and it came out as a question. I cleared my throat and wiped a stray tear. “I think my sister needs her diaper changed, but I forgot to bring her stuff with us. And I have no baby bottle or anything.” I felt guilty for letting my mom down like that. I was old enough to know better. “And my mom–what’s happening to my mom?” I knew I should have asked right away, but there were too many things happening at once. I never had to be responsible for my sister for so long by myself, and at a hospital, no less.

“I have everything our little girl needs right here,” the nurse sing-sung her way over to Nonaken. “Come here, sweetheart. There you go.” And just like that, she lifted Nonaken and checked her diaper and cleaned her up. She was like a miracle worker. One, two, all done.

“Thank you,” I said. “She probably needs some food too.”

“I have it right outside the door,” the nurse said and brought in a large tray with bacon and eggs and orange juice and a big bottle with formula. My mouth watered. “A bottle for our girl, and some eggs for you, young man. Also, here’s a hygiene kit–a toothbrush, some toothpaste, and a comb. The bathroom is through that door.” She pointed to a door just inside our hospital room.

I took the little plastic bag with goodies, grabbed my crutches from the corner next to the crib, and made my way to the bathroom. There was no point in showing off my prowess to the nurse. She had no idea how remarkably well I was moving. She had no baseline. And I could easily have tripped and fallen and ruined everything. Crutches were easy, familiar, reliable.

When I came out, the nurse just finished feeding Nonaken, who looked happy now and was playing with some toy the nurse brought for her. The woman thought of everything! I dug into my food, which was still warm. I didn’t realize I was ravenous. The eggs were good, but not as good as Uncle Charlie’s, obviously. I so wished he was there.

“The doctor will come soon and talk with you, Freddie,” the nurse said. “He will come with a social worker–”

“What?” The idea of a social worker got me spooked. “Why? We don’t need a social worker.” The nurse looked at me kindly and smiled. But instead of making me feel better, it just made me even more scared. “You didn’t tell me about Mom. How’s Mom?” I asked again.

“You know how hospitals work, Freddie. We are not allowed to discuss patients–”

“But I’m family!” I knew exactly how hospitals worked; I’d been here too many times.

“Why don’t you finish your breakfast, dear?” She changed the subject. And I could tell that she wouldn’t tell me anything. I just had to wait.

I finished up the food–who knows when I will eat next?–and took Nonaken on my lap while the nurse straightened up our room. We sat in a “family” chair, and I played with my sister’s fingers and toes–this little piggy… She always loved that.

We didn’t have to wait long. Several doctors, nurses, and social workers crowded into the room. If I were a normal kid without the extended experience with hospitals and their staff, I would not have freaked. But I knew. They all had that look–kind, grieved, sympathetic, serious, and “we know what’s best for you, child.” I knew that look oh so well. It always came with the worst news.

“Fred Keen?” the doctor asked and walked over to shake my hand. Nonaken started to cry again. She didn’t like being around so many strangers. A nurse that fed and changed her tried to take her off my lap, but Nonaken screamed even louder. It confused all those people. They looked around at each other, trying to figure out what to do about us.

“Doctor? Can you tell me what’s happening to our mom?” I asked, putting Nonaken over my shoulder and gently petting her back. She hiccupped and stopped wailing, keeping to just a few tears and lots of snot and drool. A nurse kindly supplied a towel to protect my already soaked shoulder. I guessed Nonaken was teething, on top of everything else. As she settled into chewing the towel over my shoulder, I asked again, “Mom? I need to know about Mom.”

“Your mom was very ill,” the doctor started.

“I know. I told her she needed to see a doctor,” I said.

“Do you know what was wrong with her?” someone asked.

“No. But she lost a lot of weight and was tired all the time,” I said. There were many more symptoms, but this was a hospital, and they were all professionals; it was their job to figure out what was wrong with Mom and fix it. I was happy that she was finally getting help. I told them as much. That seemed to confuse them even more.

“We are getting hold of your father,” the doctor said. I swear they teach verbal jiu-jitsu in medical school–all the doctors and nurses I’ve ever met were very practiced in question avoidance. All but Dr. Ulf.

“My doctor, Dr. Ulf, knows about my mom,” I volunteered. “He spoke to her just a week ago.”

“Dr. Ulf?” I saw a woman scribbling notes and then stepping out of the room. I figured she would look up Dr. Ulf and call him. I felt a little better. There were too many strangers who knew nothing about our family or our problems. I knew they were all trying to help, but they didn’t feel helpful…yet.

“Thank you, Freddie. It’s okay to call you Freddie?” the doctor asked.

“Sure. Everyone does. Fred Keen is my dad. I’m Freddie,” I told them. “You’ve said you couldn’t get hold of him yet?” I could swerve and dodge conversationally as well as they could. At school, it was my best defense–confuse them silly with words and they leave you alone…mostly.

“We are working on that, Freddie,” a woman not dressed in a hospital uniform said. I figured she was the social worker. For some reason, I hated her. It wasn’t rational. She didn’t do anything to me…so far. “You don’t happen to know if your dad is out of town? On a business trip, perhaps?” she asked.

“I don’t think so,” I said. But I really didn’t know–Dad was absent so much lately. And he stopped telling us when he traveled. Sometimes, when we crossed paths in the morning, I’d noticed a rolling bag, and then I knew he would be gone for a few days. But I didn’t notice anything yesterday. “I haven’t seen my dad since last morning,” I said. “It’s possible that he might be out of town.”

“I thought so,” the woman said and exchanged glances with the doctor. “Do you have other family in town, Freddie? Grandparents? Aunts?”

“I have an uncle in California. Uncle Charlie.”

The woman wrote something in her pad. “Would that be Charles Keen?”

“No. Uncle Charlie is my mother’s young brother. Charles Labelle,” I said. I was proud of myself for knowing. Somehow, I’d only learned Mom’s maiden name just a few weeks ago, accidentally, when I overheard her arguing with Dad through the floor of my room. It paid to eavesdrop, occasionally. “He used to work at Oakland Children’s Hospital. Uncle Charlie is a nurse. He helps kids with cancer.” I was very proud of him. “But he isn’t there right now.”

“Do you by chance know where he is?” the social worker asked.

“No.” I didn’t want to tell them about the conversation I had with Uncle Charlie’s friend. That was private. “But can you please tell me about Mom? How is she feeling?” I didn’t like how they were all avoiding telling me about her. “Can I go see her? I know it would make her happy to see her kids,” I added. And it was true.

You might have guessed by now that Mom died that night, and the doctors, nurses, and the social worker were just stalling until they found my dad. No one wanted to tell an eight-year-old and baby that their mom was dead. I couldn’t blame them.

We stayed in the hospital through that day until they finally managed to locate Dad. He came to pick us up in his new red convertible. It didn’t have a car seat for Nonaken or a booster for me. I held my sister tight on my lap until we got home, hoping that there wouldn’t be an accident on the way. I’m not sure what was more terrifying–my dad’s total lack of appropriate emotions or the ride home with the top down. Nonaken seemed to like it, though.

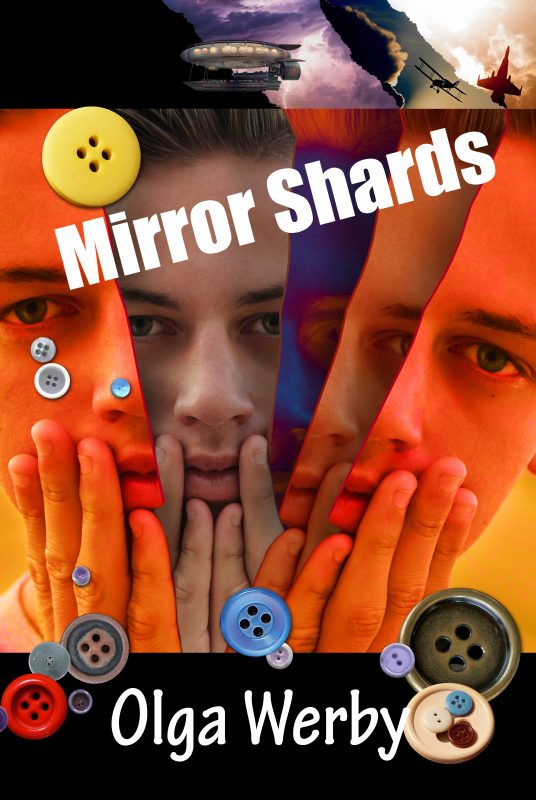

If you like what you are reading, please pick up a copy of “Mirror Shards” on Amazon or wherever books are sold.